Though I rang in the new year with a list of 14 world elections to watch in the coming year (and 14 more honorable mentions to keep an eye on), I wanted to showcase a few more thoughts about what to watch for in world politics and foreign affairs in 2014.

Accordingly, here are 14 possible game-changers — they’re not predictions per se, but neither are they as far-fetched as they might seem. No one can say with certainty that they will come to pass in 2014. Instead, consider these something between rote predictions (e.g., that violence in Iraq is getting worse) and outrageous fat-tail risks (e.g., the impending breakup of the United States).

There’s an old album of small pieces conducted by the late English conductor Sir Thomas Beecham, a delightfully playful album entitled Lollipops that contains some of the old master’s favorite, most lively short pieces.

Think of these as Suffragio‘s 14 world politics lollipops to watch in 2014.

We start in France…

1. The return of Dominique Strauss-Kahn to frontline French politics

No world leader has suffered quite as dramatic a meltdown in public confidence as French president François Hollande. Though he’s 19 months into a five-year term, his administration already has to it the feel of a powerless, lame-duck government. With an approval rating of just 15% at the end of 2013, Hollande not only hit the lowest approval of his administration, but the lowest recorded approval rating for any French president in the history of the Fifth Republic. If France were Egypt, the military would be ready to storm the Élysée.![]()

Much of the problem lies with France’s economy, which didn’t grow at all in 2012 and which will post another nearly zero-growth year in 2013. The unemployment rate has climbed to 10.9% — not as bad as Spain or Italy, perhaps, but certainly not as strong as in neighboring Germany. There’s frankly not so much Hollande can do about that, though his tortured plan to raise the top income tax rate to 75% for incomes over €1 million is now moving forward after several judicial setbacks. Hollande might have been wiser to drop the matter altogether, because that plan turned France’s wealthy and business class against Hollande from the outset of his administration. Its his ineffective leadership has turned just about everyone else in France against Hollande and much of his government, including prime minister Jean-Marc Ayrault. That’s notwithstanding a largely successful campaign to rescue Mali’s government from imminent collapse in 2013.

When Hollande marked his one-year anniversary in office, I openly wondered whether France — and the French left — would had been better off if former International Monetary Fund managing director Dominique Strauss-Kahn (pictured above) hadn’t been implicated in a scandal over potentially criminal sexual impropriety. But why not shake up French politics by rehabilitating Strauss-Kahn? It wouldn’t be the first time a disgraced figure has returned to politics. Former French president Nicolas Sarkozy brought former prime minister Alan Juppé back to the heart of government as foreign minister in 2011 after his conviction mishandling public funds in 2004.

Though he still faces charges of ‘aggravated pimping’ in France, prosecutors in New York dropped criminal charges after a hotel maid accused Strauss-Kahn of forcing himself upon her in 2011. Despite his admitted sexual peccadilloes, there’s virtually no one else in France who could restore more financial confidence than Strauss-Kahn — certainly much more than current finance minister Pierre Moscovici. While he’s at it, Hollande should also promote the only member of his government who’s managed to retain any popularity, the relatively conservative interior minister Manuel Valls, as France’s new prime minister.

At a time when France’s far-right Front national (FN, National Front) leads polls for May’s upcoming European Parliament elections, when there’s no pro-growth counterweight to the austerity politics of German chancellor Angela Merkel and British prime minister David Cameron, and when the Franco-German axis has fallen to a 60-year nadir, it’s clear to everyone that Hollande must take drastic steps to turn his government around. If he doesn’t, not only will he doom the French left by 2017, but his government won’t have the muscle to carry forward vital modernizing reforms.

Photo credit to AFP.

2. Growing authoritarianism in Kenya under the guise of anti-terrorism

The words ‘Nyumbi Kumi‘ probably don’t mean much to you, but in Kenya, they could mean the beginning of a new wave of authoritarianism, ostensibly designed to prevent further terrorism.![]()

The program, which translates to ‘ten families,’ would have each family in Kenya ‘check in’ on nine other families within their respective communities. If that sounds creepily invasive to you, with the potential for surveillance abuse, you’re not alone. Critics worry that Kenyan president Uhuru Kenyatta (pictured above), his interior minister Joseph Ole Lenku, and the Kikuyu elite that now dominate Kenya’s government will use the al-Shabab terrorist attack on Nairobi’s Westgate Mall in September 2013 as an excuse to crack down on personal liberties in what has traditionally been the hub of economic and political stability in east Africa — and one of the most dependable US allies on the African continent. The Kenyan government’s response to the Westgate assault wasn’t perfect, and the concept of Kenyan homeland defense could use some improvements. But the attack was a response to Kenya’s military invasion into southern Somalia in 2011. Angst over the program follows additional concerns about human rights abuses by Kenya’s anti-terrorism police unit.

It’s a tenuous moment in east Africa today, not just because of the lingering threat of instability in Somalia, but because of a new threat of civil war in South Sudan. Though the 2013 general election didn’t result in the same level of political violence as the 2008 election, it doesn’t mean that Kenya is no longer divided. Despite a relatively strong free-market economy, politics is split on largely ethnic lines, corruption is rife and poverty remains endemic, despite an independent commission that’s sorting through the legal minutiae of land reform. There’s a risk that Kenyatta could overplay his hand by allowing too many of Kenya’s economic gains to land in Kikuyu hands. Given the winner-takes-all nature of Kenyan politics, Kenya’s anti-terror efforts could backfire at a such a vital moment by destabilizing the country and breeding mistrust among the Luo and other rival ethnic groups.

3. Snap elections in Italy

Italy’s beleaguered grand coalition government survived a last-gasp attempt by former prime minister Silvio Berlusconi to bring about its downfall in October 2013 just days before Berlusconi, convicted and sentenced for tax fraud, was kicked out of the Senato (Senate), the upper house of Italy’s parliament.![]()

That doesn’t mean that prime minister Enrico Letta’s government is stable. The center-left Partito Democratico (PD, Democratic Party) has essentially two heads — Letta, the prime minister trying to govern what’s become a nearly ungovernable country and a new leader, young Florence mayor Matteo Renzi (pictured above), whose interests in winning the next election and becoming Italy’s prime minister in his own right aren’t exactly synchronized with Letta’s. The center-right remains split between Berlusconi’s more conservative Forza Italia, which no longer supports the government, and the Nuovo Centrodestra (the New Center-Right), led by Angelino Alfano, deputy prime minister and interior minister, which remains part of the coalition.

Though it came to power in April 2013, the government hasn’t yet tackled the two priorities with which it is tasked. The first is significant reform to liberalize and modernize the Italian economy, which has struggled to achieve growth since well before the eurozone crisis. The second is scrapping Italy’s schizophrenic electoral laws, and though no one particular loves the current iteration, which dates from the Berlusconi era, no one agrees on how to replace it.

Unless Letta can achieve a breakthrough, it leaves two options — muddling through 2014 or calling snap elections that Renzi might win (if only narrowly). But there’s no guarantee that any party or coalition could win an absolute majority under the current election law, especially in light of the continued popularity of Beppe Grillo’s protest Movimento 5 Stelle (M5S, the Five Star Movement), which opposes the Italian left and right in equal measure.

Fresh elections, therefore, could leave Italy mired in a new political crisis, another reminder much of southern Europe is still stuck in economic depression. Portugal’s government seems very likely to call new elections in summer 2014 after the expiration of its current bailout program. There’s also an outside risk that the Greek government’s narrow majority (also a left-right coalition that’s had to enact crippling budget cuts and tax increases) could dissolve. Polls there show that the anti-bailout, stridently leftist SYRIZA, the Coalition of the Radical Left (Συνασπισμός Ριζοσπαστικής Αριστεράς) would win if elections were held today.

There will be plenty of opportunities for continued political shocks to European markets throughout 2014.

4. A military coup in Venezuela.

As Venezuela slides further into economic chaos, the country’s treasury is dwindling. Inflation is rising (by around 50% for 2013), the stock of US dollars is declining and the official rate of the Venezuelan currency, the bolívar, and the actual market rate, are wildly divergent. The country’s dependence on imports are rising, the country’s oil exports are falling — and now, even the price of oil is falling.![]()

After 14 years of government dominated by socialist ideology that’s antagonized foreign investment and undermined domestic investment through ad hoc expropriations and industry-wide nationalization, it’s a wonder that the chavistas in government can still point to their chief accomplishment — significant reduction of poverty in the South American country of 30 million.

Throughout the summer, Venezuela suffered a shortage of imported goods (most notoriously toilet paper) and in the leadup to December’s local elections, president Nicolás Maduro, who was only narrowly elected over opposition candidate Henrique Capriles in April 2013, nationalized a top electronic goods chain and ordered prices lowered in a frenzy of mass shopping. Maduro may be starting to take economic reform seriously, notably by perhaps reducing the massive gasoline subsidy that keeps prices at around five cents per gallon. But we don’t know yet how serious Maduro is and whether any reforms would be too late to head off economic catastrophe.

Maduro is no Hugo Chávez — he lacks the comandante‘s populist touch, and he lacks the easy oil money that is suddenly drying up now that Maduro’s in charge. With an opposition that’s still too prim to take protest to the streets, it may take another force to dislodge Maduro if conditions get too bad.

That would be the army, which for now currently seems perfectly loyal to Maduro and the chavistas. To paraphrase Humphrey Bogart, expect a coup ‘not today, not tomorrow, but soon…’ if the economy spirals out of control. It’s not out of the question, given that Chávez and Maduro have eroded the rule of law so much already. There are few electoral outlets for change — the next parliamentary elections are in December 2015 and the next scheduled presidential election is not until 2019.

A military coup mark the largest rupture in Venezuelan governance since the Caracazo riots of 1989, but it could result in a potential shock to oil markets worldwide unless conducted in an almost pitch-perfect manner. It would leave US policymakers torn in the same manner as Egypt’s July 2013 military coup — condemn the usurpation of power through non-democratic means or delight in the collapse of Latin America’s most virulently anti-US government. It also would force the rest of Latin America to take sides, not just about Venezuela’s economy and the legacy of chavismo, which would hang in the balance, but about the schism between the business-friendly left and the populist socialist ‘Bolivarian’ left.

We know that folks like Fidel and Raúl Castro in Cuba, Bolivian president Evo Morales and Ecuadorian president Rafael Corres would support Maduro whole-heartedly. Would Colombian president Juan Manuel Santos, who faces reelection in May, and others on the Latin American right support the coup? How would Brazilian president Dilma Rousseff, who also faces reelection in October, Peruvian president Ollanta Humala, Chilean president-elect Michelle Bachelet and others on the more pragmatic left respond?

Perhaps more importantly, how will the Rousseffs, Humalas and Bachelets of the world deal with an increasingly unstable Maduro regime as the economy seems to worsen?

5. Lackluster Japanese GDP growth in 2014 and the collapse of Abenomics

The big story in Japan last year was Abenomics — the massive fiscal and monetary stimulus enacted by the government of prime minister Shinzō Abe (安倍 晋三) that’s propelled green shoots of growth in a country where deflation, sluggishness and an aging population have kept the economy in a state of near-zero growth for almost two lost decades. ![]()

At first, the shock-and-awe approach to jumpstarting the Japanese economy worked. The Nikkei, Japan’s stock index, jumped 57% in 2013, continuing a rally that began in late 2012 when the campaign for Japan’s snap elections made clear that Abe (pictured above) would return as prime minister, ready to prime the economic pump — Abe’s Liberal Democratic Party of Japan (LDP, or 自由民主党, Jiyū-Minshutō) won a massive majority in the House of Representatives, the lower house of Japan’s parliament, the Diet (国会), in December 2012, and he won another majority in the House of Councillors, the upper house, in July 2013.

But there are storm clouds on the horizon. While the year-over-year growth in Japan’s second quarter reached nearly an annualized 4%, the third quarter’s growth was a disappointment, just an annualized 1.1%. The so-called ‘third arrow’ of Abenomics — a set of rigorous economic reforms to liberalize Japan’s labor and other markets — has been slow to emerge. Meanwhile, Abe’s approval rating has fallen from around 75% in summer 2013 to around 55% or so today. Part of that is due to disapproval over his government’s controversial new state secrets law, but some of it must surely have something to do with angst over Japan’s economy. Abe’s dipping numbers may have motivated a controversial visit at the end of December 2013 to Tokyo’s Yasukuni Shrine, where the remains of several war criminals lie, angering Beijing and Seoul.

The Japanese government forecasts that GDP growth in the fiscal year starting March 2014 will shrink from an expected 2.6% to an expected 1.4%. Why? The Abe government’s decision to move forward with the increase in Japan’s consumption tax from 5% to 8%. The consumption tax hike (which is set to increase to a final rate of 10% by 2015) was the signature economic policy of the opposition Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ, or 民主党, Minshutō) during its first stint in power from 2009 to 2012. Japan also faces headwinds from the decision of the US Federal Reserve to start ‘tapering’ some of its bond and asset purchases that constitute the aggressive quantitative easing program that began in 2009.

If Abe is seen to have failed, not only will Japan have missed its biggest opportunity in a years to synchronize fiscal and monetary policy in a move to jumpstart the Japanese economy, but opponents of neo-Keynesian economic policy will be able to gloat that Abenomics has failed (no matter that the consumption tax hike could counteract the effects of the stimulus).

It will be even worse for Japan’s politics — Abe’s resignation would become increasingly likely, and it could follow a series of increasingly desperate nationalist political maneuvers. Japan would return to the era of rapidly rotating prime ministers, and both the Democrats and the Liberal Democrats will have been discredited on economic policy, opening the way to success for more unpredictable and populist parties on Japan’s far right at a time when relations with the People’s Republic of China and South Korea remain incredibly delicate.

6. A Merkel-led effort for a new European Union treaty

So now that Angela Merkel has won a near-landslide victory for her center-right Christlich Demokratische Union Deutschlands (CDU, Christian Democratic Party) and a third consecutive term as Germany’s chancellor, heading another grand coalition government that includes nearly 80% of Germany’s Bundestag, the lower house of its parliament, what does Merkel intend to do?![]()

![]()

She’ll never command the same level of broad popular support as she does today, so it’s a chance for Merkel to ‘go big.’ After eight years of cautious policymaking at home and ‘kicking the can’ within Europe, Merkel has signaled that she’ll use her political capital to press another attempt at a new European Union treaty.

Under the new EU treaty, the Mediterranean countries would receive the benefits of a wide banking union and perhaps even fiscal stimulus that could, at long last, pull countries like Italy, Spain, Portugal and Greece out of economic depression. In return, Merkel would demand centralized fiscal control at the European level, which would cement her fiscally conservative vision in EU-wide banking and fiscal policy for decades to come.

While the deal would be incredibly tricky, and there’s no guarantee that Spanish or Italian citizens, let alone Dutch or German voters, would agree to cede so much more sovereignty, it would pull the European Union a long way toward truly becoming the ‘United States of Europe.’

It would also nod to the reality of a multi-speed Europe, perhaps by relaxing the requirements on Poland and other new EU members to enter the eurozone (the same concession that the United Kingdom and Denmark enjoy). As British prime minister David Cameron has pledged to hold a referendum on EU membership in the United Kingdom if he’s reelected in 2015, Merkel could deliver opt-outs to Cameron on justice, migration or other issues that would allow him to claim victory at home in a way that neutralizes a highly euroscepetic constituency on the English right. Cameron, who largely agrees with Merkel’s view on austerity, could wind up increasing the likelihood both of his own reelection and the chances that he’ll be able to win a future EU referendum.

7. The release of Mir-Hossain Mousavi in Iran

Congressional Republicans — and even more than a few Congressional Democrats — are threatening to pass yet another bill of US economic sanctions against the Islamic Republic of Iran, which now presents the biggest US-based obstacle to a potential deal between the ‘P5 + 1’ negotiators (the permanent members of the UN Security Council, plus Germany) and Iran over its nuclear program.![]()

With Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu still demanding that any deal provides for zero enrichment within Iran, his US friends allied with the bipartisan American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC) could stall a rapprochement between Iran and the United States under the leadership of Iran’s new reformist president Hassan Rowhani, who was elected in a rare first-round victory in June 2013. If Netanyahu and his US allies in Washington succeed, it will mark another chapter in a long volume of failed opportunities vis-à-vis Iran since the 1979 revolution.

But Rowhani still has one symbolic card to play that would resonate with Iran’s skeptics worldwide. That’s the release from house arrest of Mir-Hossain Mousavi (pictured above), the 2009 presidential candidate, leader of that year’s ‘Green Movement,’ and a former Iranian prime minister in the 1980s. While Mousavi’s release would almost certainly inflame Iran’s hardliners, Rowhani certainly wouldn’t be able to do so without the assent of supreme leader Ali Khamenei.

In one move, Rowhani could show to the world that he’s serious about a more liberal Iran. It’s a step that would give Iran great headlines almost instantly, with the effect of maximizing Iran’s global goodwill. Don’t be surprised if Mousavi’s release comes at a time of extreme strategic importance for Rowhani — once deployed, it would likely signal the high-water mark of Rowhani’s muscle within Iran, not only vis-à-vis Khamenei, but also against the more conservative principlist camp.

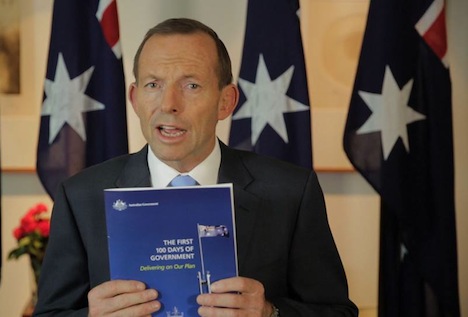

8. A double dissolution election in Australia over the carbon tax

Though prime minister Tony Abbott won a solid victory in September 2013, returning his conservative Liberal/National Coalition to power after seven years in opposition, he’s already got his eye on another potential high-stakes election as soon as July 2014. ![]()

That would be a double dissolution election, which would essentially amount to a full election of the entire Australian parliament — in typical elections, including the most recent one, all of the members of the House of Representatives are elected, but only one-half of the Senate is elected. That’s left Abbott (pictured above) without control of Australia’s hung Senate, where the Australian Labor Party and its leftist allies can block Abbott’s legislation from the lower house.

The key issue that would ignite a double dissolution is the climate change policy introduced by the previous Labor government, which instituted a scheme of temporary carbon taxes that will permanently become a carbon trading program. Abbott is essentially betting that Labor will back down and agree to dismantle the relatively unpopular carbon scheme, or otherwise face further political annihilation in a new election. It would be a difficult test for the Labor Party in what was supposed to be a new, less divisive era after the infighting between former leaders Kevin Rudd and Julia Gillard. If its new leader Wayne Shorten loses even more seats in a double dissolution contest, it could not only usher in a new era of conservative dominance within Australia, but give Abbott a wide majority on issues that extend well beyond climate change — to asylum policy, economic policy and foreign affairs. It could also influence the courage of governments worldwide, including the US government, to attempt to tackle climate change in the years ahead.

Within Australia, it could also end Shorten’s tenure as the ALP leader, potentially (and incredibly) paving the way for a third act (!) for Rudd, though it’s more likely that Rudd’s longtime deputy prime minister Anthony Albanese, who finished a close second in the recent ALP leadership race, and is a favorite of the party rank-and-file, would be available to step up if Shorten fails.

9. The bloodiest post-independence year for Central Africa

Can you imagine what the world would look like with new branches of al-Qaeda throughout west and central Africa? Forget about al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb — consider the emergence of al-Qaeda in Central Africa or even al-Qaeda in the Sahel.![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

It’s not as outrageous as it sounds.

In the final days of 2013, two crises in central Africa escalated in rapid succession. The first is a potential civil war in South Sudan, a political conflict between president Salva Kiir and former vice president Riek Machar that could escalate into an ethnic conflict in the world’s newest country that could leave its vital oilfields vulnerable. The second is the failure (so far) of a French peacemaking force in the Central African Republic to restore stability to a country that’s been shaken by a coup in March 2013, when the Séléka rebel coalition ousted current president François Bozizé. Since the coup, the country’s only gotten worse — though rebel leader Michel Djotodia was sworn in as president in August 2013, the country has descended into further violence between Christians, who comprise about 80% of the population, and Muslims, who comprise just 10%, but who disproportionately populated the Séléka rebels.

Nigeria, a massive country of 169 million people with so much oil wealth that it’s set to overtake South Africa as the largest sub-Saharan economy in the coming years, is also split on even more difficult north-south and Christian-Muslim lines (the pro-sharia Islamic group Boko Haram that continues to agitate in northeastern Nigeria present an especially tricky challenge). The country’s dominant Peoples Democratic Party risks splitting over whether to endorse president Goodluck Jonathan for reelection in 2015.

In the sprawling Democratic Republic of Congo, the end of the Second Congo War in 2003 and Joseph Kabila’s November 2006 election helped stabilize sub-Saharan Africa’s largest country by area (with nearly 76 million people). But though the M23 rebels in eastern Congo agreed to a ceasefire in November 2013, the entire country remains on shaky ground, and Kabila’s term-limited tenure is set to end in 2016.

That’s to say nothing about the Sahel. Though Mali and Mauritania conducted parliamentary elections in December 2013, each have wide-ranging problems. Mauritania is a potential future staging ground for terrorists and a haven for human slavery, while Mali’s new democratically elected president Ibrahim Boubakar Keïta will face the challenge of peace talks with separatist Tuaregs in Mali’s north, who have fought for autonomy and/or independence since Mali’s own independence from France in 1960. A Tuareg rebellion in early 2012 that prompted a military coup in Mali and, later, the infiltration of international Islamist jihadists who threatened to take over all of Mali until French intervention. Other countries in the Sahel, such as Niger, Chad and Burkina Faso, face even less tenuous holds on government, combined with severe water insecurity issues, economic development problems and human rights and poverty concerns.

Many of sub-Saharan Africa’s problems lie in the haphazard borders that its colonial masters placed upon Africa’s new states in the independence era — which is why, perhaps, it’s no surprise that tribal, ethnic and religious conflicts continue to fuel violence more than a half-century into the post-colonial era.

At a time when so much of southern, west and southeastern Africa is thriving economically, a two-gear Africa is emerging — one that’s in reach of achieving developmental gains or even low-middle-income status and one that’s falling into complete post-colonial disarray. It’s worrisome, but the ‘losers’ of the sub-Saharan economic boom could all face a future of intense political violence in 2014, making them ever more susceptible to influence by radical Islamists.

Photo credit to Reuters / Luc Gnago.

10. A succession crisis in Saudi Arabia

What happens if Saudi Arabia’s king, Abdullah bin Abdulaziz Al Saud, dies in 2014? (And what happens even if he doesn’t?)![]()

The 89-year-old monarch (pictured above) isn’t in the best of health, and he hasn’t been incredibly healthy since at least 2010. He allegedly had a heart attack in late 2012 when he went to New York for treatment.

In November 2012, the first grandchild of Ibn Saud (King Abdulaziz) — the monarchy’s third generation — came to a prominent government position when Prince Mohammed bin Nayef became the Saudi interior minster. Since Abdulaziz’s 1953 death, the kingdom has been ruled by his many sons in a horizontal monarchy that passes from brother to brother. But the brothers are dwindling in number, and those who remain, like Abdullah (pictured above), are increasingly old. The current crown prince, who would take over if Abdullah dies, is the 78-year-old Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Saud, Abdulaziz’s 25th son. Crown princes are selected through an opaque system, despite Abdullah’s efforts to establish a committee of each of the remaining brothers (or their first-born sons) to select crown princes in the future.

Abdullah (who is Abdulaziz’s 10th son) has governed the kingdom since 2005, but he’s been the de facto ruler of Saudi Arabia since 1995. The gerontocratic system has left an increasingly infirm generation calling the shots with no plan to hand power to the next generation in an orderly fashion.

Since it’s literally one of just a few countries in the world governed by absolute monarchy, it’s not surprising that Saudi leadership seems as stagnant as ever these days. On so many issues, Saudi Arabia’s monarchy seems out of sync with the times and unable to match demands for reform. It’s largely replaced the United States as the chief donor to the military government in Egypt that toppled Mohammed Morsi, a move that’s inflamed the Wahhabist elite sympathetic to Morsi and Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood. The kingdom, even by Middle Eastern standards, continues to deny women the basic privileges to drive or to work. It picked a high-profile fight with the United States by refusing to accept a non-permanent seat on the UN Security Council in protest against the Obama administration’s refusal to launch military strikes against Syria’s president Bashar al-Assad and the Obama administration’s growing optimism over a long-term nuclear deal with Iran.

At home, the monarchy faces growing tension as well. Can the House of Saud continue to buy its way out of political reform with ever greater amounts of oil spending? The kingdom faces increasingly difficult economic conditions, including high unemployment, to say nothing of women’s rights and growing skepticism from the Saudi religious elite.

A succession crisis (or even the failure of the Saudi monarchy to reform from within) could bring forward massive popular protests, which would make the Arab Spring look like a mere appetizer to a hot, long Arab Summer — and no one knows whether Salafists, Wahhabists, moderates, liberals, competing oil sheikhs or competing House of Saud princelings might ultimately control the pivotal country. Political uncertainty in Saudi Arabia could roil oil markets and transform just about every major issue in the Middle East today.

11. Same-sex marriage enacted in Vietnam

2013 was a landmark year in the struggle for gay rights and, in particular, marriage equality.![]()

France, rather contentiously, enacted full same-sex marriage rights, and England, rather less contentiously, did the same (with Scotland to follow soon). Although German chancellor Angela Merkel has not advanced a legislative solution to marriage equality, Germany’s top constitutional court, the Bundesverfassungsgericht, has been systematically granting LGBT couples the same rights of other married couples, including in 2013 federal tax benefits. In the United States, ten additional states, from New Mexico to Minnesota to Illinois, joined eight others (plus the District of Columbia) in recognizing same-sex marriage. That follows two key US Supreme Court rulings in 2013, Hollingsworth v. Perry, which reversed Proposition 8, a California ballot measure, in effect reinstating same-sex marriage in California, and United States v. Windsor, which struck down the 1996 Defense of Marriage Act as unconstitutional, therefore allowing all of the federal benefits of marriage to married same-sex couples.

It was also a year that reminded us that the world is moving on LGBT rights at different speeds. In contrast, Russia suffered severe global criticism in the leadup to the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi for its horrific LGBT rights record (to say nothing of its human rights record more generally). India’s LGBT community was shocked in December 2013 when the Indian Supreme Court re-criminalized same-sex conduct by reinstating the notorious Section 377 of India’s penal code.

But Vietnam could this year become the first country on the Asian mainland to enact full marriage equality. In September 2013, Vietnam’s Quốc hội (National Assembly) voted to abolishing fines on same-sex marriages without necessarily recognizing it. Given the breakneck pace that Vietnam is moving on LGBT rights, it’s perfectly plausible that the National Assembly could fully legalize same-sex marriage in Vietnam this year — a historic landmark for global LGBT rights.

Gender, sexuality, family, marriage and individuality are conceptually much different in east and southeast Asia than in the rest of the Western world. But the Vietnamese enactment of marriage equality would mark a precedent for mainland Asia. It would also make Vietnam, a communist regime governed since 1975 solely by the Đảng Cộng sản Việt Nam (Vietnamese Communist Party), more progressive on the issue of LGBT rights than the United States, where Vietnam still conjures complicated feelings due to the US war there in the 1960s and 1970s. It’s a development that could be potentially more important than the gradual opening of Burma/Myanmar to political and economic liberalization in recent years.

Photo credit to AFP.

12. A constitutional crisis in Spain over the Catalan independence referendum

When Catalan regional president Artur Mas and a majority of regional lawmakers set a date for a November 2014 referendum on Catalan independence, it was the latest provocation in a war of wills between Barcelona and Madrid, where Spanish prime minister Mariano Rajoy has refused to permit a vote, declaring the referendum unconstitutional.![]()

![]()

Today, the referendum seems more smoke than fire — a way for Mas (pictured above) to capitalize on Catalan unrest over Rajoy’s refusal to allow them a vote on self-determination and the economic crisis that’s left both the relatively wealthier Catalunya and the poorer regions of Spain struggling.

What does Mas want? Perhaps an independent Catalunya, but more likely greater autonomy over taxes and finances. Catalans resent the transfer of wealth from their region to less economically productive regions of Spain. But the Catalan independence movement goes much deeper — Catalans have a separate language and a distinct culture that Spanish dictator Francisco Franco cruelly attempted to stifle throughout the 20th century. Rajoy’s refusal to consider a vote or to negotiate with Mas has to it some of the same disrespect that Catalans felt under Franco.

Rajoy, for his part, is struggling to keep Spain’s finances afloat and its reputation in global credit markets stellar. He needs every last euro he can spare. What’s more, if he starts to negotiate with Catalan leaders, Basque leaders in Euskadi, where separatists also control the local government, could try to negotiate for greater autonomy. Other regions like Galicia or Andalusia could follow suit, quickly unraveling Spain’s central government.

Expect both Rajoy and Mas to play chicken throughout 2014. One likely outcome is that Mas cancels the referendum in exchange for concessions from Rajoy to hold a future vote or greater regional control.

Another likely outcome is that the referendum goes forward, but the result is inconclusive (i.e., Catalan voters agree that Catalunya is a ‘state,’ but not an independent ‘state’). Rajoy doesn’t stop the vote, but neither does he legitimize it, either.

But the risks are so great, and the territory so uncharted, that Spain could find itself in a constitutional crisis. It’s not necessarily that Rajoy would send tanks into the streets of Barcelona, but there are any number of nightmare scenarios that could result if the standoff spirals out of control — with no EU precedents on how to deal with secessionism. That makes the Catalan independence movement, even more than snap elections in Italy or Greece, the most significant political risk to the eurozone in 2014.

13. Fast-track trade authority for US president Barack Obama

There’s no greater low-hanging fruit in the world economy in 2014 than the successful passage of robust trade liberalization through the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) between the United States and the European Union and the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) among the United States, several Asian-Pacific countries and several Latin American countries.![]()

Nothing would catalyze the negotiations more than a vote by the US Congress to grant ‘fast-track’ authority to US president Barack Obama. A ‘trade promotion authority’ (TPA) bill would allow Obama to negotiate TTIP and TPP and send the negotiated deal directly to Congress for an up-or-down vote, without the risk that members of Congress could amend or filibuster the trade deals, thereby making the conclusion of either trade deal much easier. The most significant benefit to fast-track authority is that it would eliminate the ability of a single member of Congress to take TTIP or TPP hostage (for any reason possible).

The World Trade Organization’s new director-general, former Brazilian diplomat Roberto Azevêdo took office in September 2013 and promptly closed the Bali Agreement in December 2013, the first significant step in the Doha round of trade negotiations that’s stretched for more than a decade. The Bail Agreement improves and streamlines global customs procedures, which will make the shipment of goods globally cheaper.

But in terms of world trade, Doha and the WTO will still play second fiddle to TTIP and TPP. The two deals face significant pressures on their own merits, including French reluctance over liberalizing agricultural markets with respect to TTIP and Japanese reluctance to join negotiations over TPP, which would create a free-trade zone that includes New Zealand, Mexico, Chile, Peru, Vietnam, Singapore, Malaysia, Australia — and potentially Japan, Taiwan and South Korea.

If the US Congress passes a TPA bill in early 2014, it will mark a rare moment of bipartisan unity between pragmatic Republicans and Democrats on Capitol Hill, but it could also catalyze talks on both sides of both oceans.

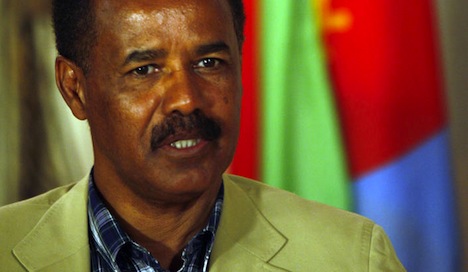

14. The death of Eritrean leader Isaias Afwerki

Rumors have swept for years that Eritrea’s longtime strongman, Isaias Afwerki, is ailing. Could 2014 be the year that actually proves the rumors true?![]()

Afwerki (pictured above) runs one of the oddest, most autarkic regimes in sub-Saharan Africa with an iron fist, and it’s left the country chiefly in a state of suspended economic animation. Old (and young) men sit in cafes in the capital city of Asmara with little to do, and emigres wait for the day when Eritrea has a leadership that’s interested in integrating Eritrea into the wider world — or even mending relations with its longtime rival Ethiopia following the death of longtime Ethiopian leader Meles Zenawi in August 2012.

It’s hard to remember the high hopes that accompanied Eritrea’s independence from Ethiopia in 1993. Meles, who led the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (the TPLF, ሕዝባዊ ወያኔ ሓርነት ትግራይ), based in northern Ethiopia, pushed the communist Derg regime of Mengistu Haile Mariam out of office in 1991, the same year that the Eritrean People’s Liberation Front (the EPLF, ህዝባዊ ግንባር, ህግ) entered Asmara. Meles and Afwerki worked together to bring down the Derg and, initially, Meles and Afwerki were thought to be highly complimentary leaders who would lead Ethiopia and the nascent Eritrea to a new, more positive chapter in Ethio-Eritrean relations. Instead, by 1998, the two countries were fighting a border war that resulted in nearly as many casualties in two years as in the decades of the EPLF’s fight for independence. The two countries have skirmished in the years since, and the newly landlocked Ethiopia moved most of its port business to Djibouti to Eritrea’s south.

Since 1998, Afwerki has become increasingly authoritarian, and today, the world is playing the same game with Eritrea that it’s playing with North Korea in Asia and with Belarus in Europe — waiting out the end of a nearly totalitarian government.

A reported coup attempt in January 2013 was easily thwarted, but Afwerki’s death could bring a renaissance for Eritrea, which once featured some of the best infrastructure of Italy’s short-lived colonial empire. At age 67, he’s outlived Meles by a decade, though he spent much of his early life in the harsh conditions of a guerrilla fighter for Eritrean independence. Afwerki had to take steps in early 2012 to dispel widespread reports that his health was on the wane.

Afwerki’s death could pave the way for smarter economic policy, a leap toward modernization and liberalization, and most importantly, a thaw in relations with Ethiopia. But we know so little about Eritrea today that Afwerki could be the only institution holding the country together. So there’s also a risk that his death would mean an uptick in instability, which might provide a new safe haven for al-Qaeda or al-Shabab. That too could complicate relations with Ethiopia, which itself will soon have (or already has) a Muslim-majority population.

“If France were Egypt, the military would be ready to storm the Élysée.”

This is the exactly the kind of dumb aside that you don’t want on a site like this that emphasizes its perspective and insight. For two reasons:

1. Egypt is possibly THE WORST example of an unstable, revolution-prone country. Almost until the revolution, Egyptologists were convinced that no serious revolution would take place, given the country’s long history of stability in the face of conditions that would be untenable elsewhere.

2. The French don’t like their leader, Egyptians didn’t like their government. That’s a big difference, and it’s so elementary I don’t need to explain further.

I know it was a throwaway comment – essentially a joke. But a joke has to rest on some sort of underlying premises, and the premises behind this joke was all kinds of faulty. I’d accept it in amateur blogging but Suffragio should be better than this.

This is a point well taken. The underlying basis here is that François Hollande today may actually be less popular than Mohammed Morsi was in July 2013 — to the point where some people are credibly asking if Hollande might actually mark the end of the Fifth Republic (http://www.slate.fr/tribune/82121/francois-hollande-mort-cinquieme-republique). So it might have been more accurate to say “If France were Egypt in 1952 or 2011 or 2013…” The subtle point was to underline that France’s democratic institutions can withstand the virtually universal disdain for its elected leader, while Egypt’s nascent democratic institutions cannot. In places like Egypt, that means popular protests lead to military coups; in places like France, it means that presidents, in order to be effective, have to shake up either policy and/or personnel (as the discuss further proceeds). But I get it — and appreciate the criticism.

“Bali” supposed to be “Bail” and I’m guessing ” in the United Kingdom if he’s reelection in 2015″ is supposed to be “if he’s reelected”.. Just some typos for ya that slipped proof reading and spell checking. Just trying to help. Nice article covering many more bases than I expected.

Great catch, thanks! (Though it *is* the Bali Agreement!)