Last week, I noted that German chancellor Angela Merkel succeeded in achieving the post-partisanship in Germany that US president Barack Obama had hoped to achieve when he ran for president in 2008.![]()

While that’s somewhat of an unfair comparison given the collegiality and consensus that’s developed in Germany’s postwar politics, there’s perhaps a lesson for US politicians to learn from the example of German politics in resolving the current standoff that has shut down the federal government of the United States and threatens to precipitate a sovereign debt crisis later this month over the US debt ceiling.

Even after Merkel’s center-right Christian Democrats won a once-in-a-generation landslide victory, she remains five seats of an absolute majority in Germany’s Bundestag (the lower house of the German parliament) and well short of a majority in the Bundesrat (the upper house), so she’s locked in negotiations — likely for the rest of the year — to form a viable governing coalition with either her rival center-left Social Democrats or the slightly more leftist Green Party.

Contrast that to the United States, where a minority of a party that controls one-half of one branch of the American government has now succeeding in effecting a shutdown of the US government.

In the US House of Representatives today, speaker John Boehner (generally) operates on the ‘Hastert rule.’ He’ll only bring bills to the floor of the House that are supported by a ‘majority of the majority’ — a majority of the 232-member Republican caucus. So even if 115 Republicans and all 200 Democrats in the House support a bill, such as a clean ‘continuing resolution’ to end the current shutdown, they won’t be able to do so if 117 Republicans prefer to condition a continuing resolution upon a one-year delay of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, popularly known as ‘Obamacare.’

It’s not uncommon in parliamentary systems for the ‘loyal opposition’ to sometimes lend their support for an important piece of legislation. Earlier this year in the United Kingdom, British prime minister David Cameron passed a marriage equality law only with the support of the opposition Labour Party in the House of Commons in light of antipathy within a certain segment of the center-right Conservative Party to same-sex marriage.

In country after country in Europe, including Greece, Ireland and Latvia, traditional rivals on the left and right have sucked up the political costs of austerity and voted to accept difficult reforms, tax increases and tough budget cuts in the face of rising unemployment and depression-level economies in order to avoid the further tumult of being pushed out of the eurozone’s single currency. If Italy’s left and right could support former prime minister Mario Monti’s technocratic government for 15 months, it’s not outside the realm of democratic tradition to believe that Boehner could form a working coalition in the US House to resolve a crisis that threatens not only American political credibility in the world and the American economy, but the entire global economy.

But as Alex Pareene at Salon wrote earlier today, the United States doesn’t have a parliamentary system, it has a presidential system where an opposition party that controls one house of Congress can cause a crisis if it wants to do so:

An American parliamentary system with proportional representation wouldn’t immediately or inexorably lead to a flourishing social democracy, but it would at least correct the overrepresentation of an ideological minority, and cut down on intentional tactical economic sabotage. The reason we’re in permanent crisis mode isn’t “extremism,” but a system of government that guarantees political brinkmanship.

There’s a bit of ‘grass is always greener’ mentality to that counterfactual. Parliamentary systems come with their own set of difficulties, and governments in parliamentary systems can wind up just as paralyzed as the current American government seems to be — former Italian prime minister Silvio Berlusconi is causing a political crisis this very week in Italy that will culminate in a vote of no confidence on Wednesday against the fragile coalition headed by center-left prime minister Enrico Letta. Though the government’s been in power for just five months, Italy could face its second set of elections in 12 months if Letta’s government falls. Belgium famously went without a government for 535 days between 2009 and 2011 because no majority coalition could form a government. Moreover, minority governments in parliamentary systems often lurch from crisis to crisis, with individual lawmakers willing and able to ‘hold up’ the government’s legislation.

But the United States need not change its entire system of government to take away a few lessons from Merkel and from Germany.

Juliet Eilperin and Zachary A. Goldfarb at The Washington Post suggested earlier Tuesday that Boehner make a push to become the first truly bipartisan speaker:

[T]he press tends to trumpet two unflattering themes: that Boehner can neither manage his own conference nor make a credible deal with the White House. As a result, the narrative runs, Americans are left careening from fiscal crisis to fiscal crisis, and Congress can’t even tackle popular initiatives such as immigration reform. A host of other potential changes supported by huge swaths of both parties — from tax and entitlement reform to infrastructure spending — are also left on the table just because of the fallout Boehner faces from a few dozen, ultra-conservative Republicans.

At least that’s the rap against Boehner, whose speakership so far has been defined by blocking Obama’s priorities rather than producing significant laws. But that could all change if he were just to decide to say to House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.): “Let’s enter a grand coalition. Democrats will vote for me for speaker as long as Republicans hold a majority. And we’ll do a budget deal that raises a little bit of tax revenue and reforms entitlements. We’ll overhaul the tax code for individuals and businesses. We’ll pass immigration reform and support the infrastructure spending that the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and labor unions want.”

Call it a pink-blue coalition — the moderate Republicans and the Democrats. (Or maybe the donkey-rhino‡ coalition).

The concept of a ‘grand coalition’ deal in the United States seems fanciful today, and Boehner’s spokesperson rejected the notion outright:

Or, as Boehner spokesman Brendan Buck reacted to the idea in an e-mail, “This is so asinine the Washington Post should be embarrassed it wasted anyone’s time with it.”

But after a weeklong shutdown? Two weeks? More?

Imagine if minority leader Nancy Pelosi (and House minority whip Steny Hoyer) called Boehner’s bluff by promising sufficient Democratic votes to support his speakership in order to resume the federal government and to raise the US debt ceiling. Would Boehner take that deal? It might not even need to come to that if Boehner simply allowed a free up-and-down vote on funding the government. With Democratic support, a minority of the Republican caucus could pass a continuing resolution, which would also pass in the US Senate, where Democrats hold a 54-46 advantage. The central question to the shutdown crisis now seems to be whether Boehner can do so without jeopardizing his position as speaker of the House.

It wouldn’t be entirely unprecedented — if you think about congressional politics from, say, the 1930s through the 1960s, it’s almost as if the United States featured a three-party system: Republicans, ‘National’ Democrats and ‘Southern’ Democrats. In that light, the coalition that passed perhaps the most important legislation of the last half of the 20th century — the Civil Rights Act of 1964 — was a cross-party coalition. Northern Democrats supported the law by a margin of 145 to 9 and Republicans by a margin of 138 to 34, while Southern Democrats almost wholly opposed it by a margin of 7 to 87. Sure, a handful of Republicans, notably then-senator Barry Goldwater, opposed the law, and technically, pro-civil rights Democrats outnumbered anti-civil rights Democrats within the party caucus. There wasn’t a rule that both northern and southern Democrats had to agree on an issue in order for the Congress to pass legislation in the middle of the 20th century, but Republicans and southern Democrats routinely worked together to pull Congress in a more conservative direction.

A more recent example? Former Republican president George H.W. Bush signed the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990, which raised US income tax rates but also put the country’s finances on the path to a budget surplus. Though he suffered massive criticism from the conservative right for reneging on his famous ‘read my lips — no new taxes’ pledge, the 1990 budget passed the House of Representatives on a narrow cross-coalition of moderate Democrats and Republicans. The bill won just 47 of 173 Republican votes and 181 of 255 Democratic votes. The spread was even more narrow in the Senate.

Even in early October 2008, in the first days of the financial crisis from which the US economy is still recovering, Republican president George W. Bush (and treasury secretary Hank Paulson) won congressional support for the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) to provide relief to the US financial sector by a cross-party coalition. In the US House, TARP passed with 172 of 235 Democratic votes and just 91 of 199 votes from Republicans — and that came after a 777-point drop in the Dow Jones Industrial Average a week earlier when the first House vote on TARP failed on a 228-205 defeat.

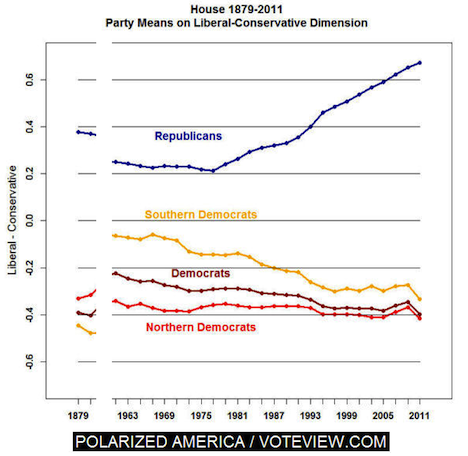

But over the past two decades, the two parties have only become more polarized, as a cohort of American political scientists have shown and as James Fallows at The Atlantic highlighted earlier Tuesday:

[T]he trend is this: in both the House and the Senate, Democrats are slightly more liberal than their historic norm, and Republicans are significantly more conservative than at any other time on record.

While both parties have veered from the center since around the mid-1970s, Democrats have become only slightly more liberal — and you can explain that change largely in the transformation of the American South from universal Democratic stronghold to Republican heartland, which began in the wake of the civil rights era. The Republicans, however, have become increasingly much more conservative.

There are certainly many reasons for that — the fact that the natural conservatism of Southern politicians moved from the Democrats to the Republicans, but also the importance of primary elections in a system where ‘gerrymandered’ districts make general election victories all but assured for most House incumbents (both Republican and Democratic), the end of congressional earmarks (which gave congressional leaders some check upon their caucus), the influence of money in political campaigns, the increasingly shrill tone of right-wing and, increasingly, left-wing media that began in the 1990s with Rush Limbaugh’s success as a conservative radio host and the advent of Fox News.

All of which helps to explain why the United States has reached this point, where a minority of House members can shut the entire government down over a law that was enacted in 2010 and was upheld by the US Supreme Court last summer.

What it doesn’t readily explain is how Boehner, Obama and House Democrats might find a way to end Washington’s current debilitating standoff.

* * * * *

‡ A reference to the pejorative RINO — ‘Republican in Name Only’ that especially conservative Republicans sometimes apply to more moderate Republicans.

Many thanks to Sean Callaghan for his insight as I worked through this post.