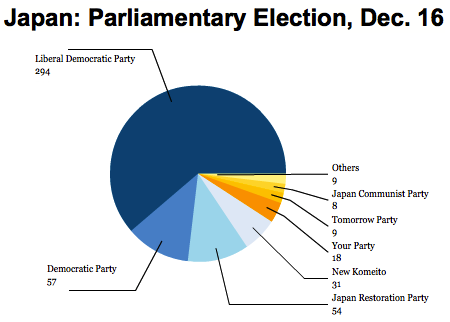

Well, that was quite a blowout. Just a little more than three years after winning power for the first time in Japan, the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ, or 民主党, Minshutō) was reduced to just 57 seats in a stunning rebuke in Sunday’s Japanese parliamentary elections.

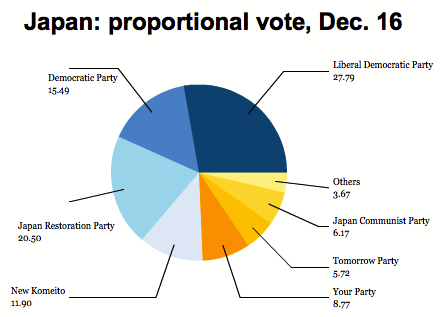

Shinzō Abe (安倍 晋三), former prime minister from 2006 to 2007, will return as prime minister of Japan, and the Liberal Democratic Party of Japan (LDP, or 自由民主党, Jiyū-Minshutō), which controlled the House of Representatives, the lower house of Japan’s parliament, the Diet, for 54 years until the DPJ’s win in 2009, has seen its best election result since the early 1990s, with 294 seats. Among the 300 seats determined in direct local constituency votes, the LDP won fully 237 to just 27 for the DPJ. An additional 180 seats were determined by a proportional representation block-voting system, and the LDP won that vote as well:

In contrast, the DPJ has fallen from 230 seats to 57 seats — by the far the worst result since it was created nearly two decades ago. Its previous worst result was after the 2005 elections, when the popular reformist LDP prime minister Junichiro Koizumi (小泉 純一郎) won an overwhelming victory in his quest for a mandate to reorganize and privatize the bloated Japanese post office (a large public-sector behemoth that served as Japan’s largest employer and largest savings bank).

Outgoing prime minister Yoshihiko Noda (野田 佳彦) has already resigned as the DPJ leader, and a new leader is expected to be selected before the new government appears set to take office on December 26.

The result leaves Abe with the largest LDP majority in over two decades — together with its ally, the Buddhist, conservative New Kōmeitō (公明党, Shin Kōmeitō), led by Natsuo Yamaguchi (山口 那津男), which increased its number of seats by 10 to 31, Abe will command over two-thirds of the House of Representatives, thereby allowing him to push through legislation, notwithstanding the veto of the Diet’s upper chamber, the House of Councillors.

It’s a sea change for Japan’s government, and we’ll all be watching the consequences of Sunday’s election for weeks, months and probably years to come. Just a full working day after the election, events in Japan’s politics are moving at breakneck speed.

For now, however, here are 12 of the top takeaway points from Sunday’s election:

1. Economic policy. The most salient issue for Japanese voters was Japan’s economy — and Abe’s campaign platform on both fiscal policy and monetary policy was incredibly bold. In short, Abe (pictured below, right) and the LDP have pledged to combat what appears to be a new deflationary recession in Japan, with the purchase of additional bonds to spend up to ¥200 trillion ($2.4 trillion) on infrastructure spending and other public works. Abe has also stated he will push the Bank of Japan, despite its long history of political independence, to buy the Japanese government’s bonds. Immediately after Sunday’s election, Abe suggested that the new government could pass a supplement to the 2012 budget to enact such spending as soon as possible. Japan’s public debt is already the world’s largest, in terms of its size relative to GDP — currently around 230%, with the LDP’s spending to push it much closer to 300%, and possibly nudging Japan toward a debt crisis.

Abe has additionally called on the BOJ to set at least a 2% or even 3% inflation target and to engage in more expansionary monetary policy (i.e., quantitative easing). Although he cannot dictate policy to the BOJ, the LDP’s extensive win on Sunday will place extraordinary pressure on the BOJ to pursue a more expansionary policy. Notably, Abe’s government will determine who will succeed the BOJ’s current governor Masaaki Shirakawa (白川 方明), whose five-year term ends in April 2013.

Investors certainly believe Abe, with the yen falling to its lowest level in over 20 months in Monday’s trading.

Although the LDP agreed to support a raise in Japan’s consumption tax from 5% now to 10% by 2015 (to begin phasing in by 2014), Abe’s government could well decide to delay or reverse the sales tax increase, one of the DPJ’s top legislative accomplishments while in government.

2. Foreign policy and Article 9. Second only to the economy are multiple interlinked issues that all revolve around the future of Japan’s military. That includes an ongoing showdown with the People’s Republic of China over three of the remote Senkaku islands that Japan purchased earlier this autumn.

Abe has called on revising Japan’s constitution to make it easier to pass amendments — currently, two-thirds of each house are required in order to approve an amendment, which then must be approved by national referendum; Abe wants to reduce the Diet requirement to just a simple majority vote. He also wants to revise Japan’s famously pacifist Article 9 to allow for a more normal military, not the purely defensive military that characterizes Japan’s current Self-Defense Force, in part to to allow Japan to take a more aggressive posture with China or other countries in East Asia.

At a minimum, Abe seems sure to revise longstanding government interpretation of Article 9 to allow for Japan’s Self-Defense Force to engage in collective-self defense, allowing it to join allies, such as the United States, in collective military action throughout the world.

3. Pending House of Councillors election in August. Although Abe and his allies will control a veto-proof majority in the House of Representatives, the LDP will face its first major electoral test within seven months, the date by which elections must be held for Japan’s upper house (where the DPJ still holds a plurality, though not an absolute majority, of seats).

Today, it surely seems like the LDP will easily wipe out the DPJ’s advantage in that election as well. But seven months is a long time in Japanese politics — especially during an era when the country’s about to have its seventh new government in seven years. So if by August, Japanese voters are angry with the LDP and its allies, it can just as easily send a message to the LDP — especially in light of the fact that Sunday’s election was much more a rejection of the DPJ than a vote of approval for the still relatively unpopular LDP. The net effect will be that Abe and his government will be on their best behavior between now and August 2013 — that means aggressive action on the economy (Abe will want to be able to demonstrate progress), but that Abe and his more hawkish allies may wait until after the next election to show their true colors on Article 9 and on Chinese relations.

4. US relations. The United States has reason to welcome Abe and the LDP back into government for many reasons, not least of which because Abe has been such an outspoken proponent of Japanese-American cooperation on security in East Asia at a time when the United States is looking to increase its role in the Asia/Pacific region as a counterweight to growing Chinese strength. Contrast that to 2009 when incoming prime minister Yukio Hatoyama (鳩山 由紀夫) came to power on the promise of eliminating or significantly rolling back the U.S. military presence in Okinawa, where Kadena Air Base serves as the main American air hub for the Pacific region.

With difficult fiscal and tax negotiations of his own in the United States, and with Europe essentially retreating to a position of austerity from the United Kingdom to Greece, U.S. president Barack Obama is likely to welcome a government that’s now perhaps the most committed within the developed world to expansionary and activist economic policy to spur employment and GDP growth.

During the campaign, the LDP formally opposed the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a growing free-trade agreement currently under negotiation among several countries (including the United States, Canada, Australia, Chile, Peru, Mexico, Malaysia, Singapore and Vietnam), it seems like its opposition was more political than substantive, given Noda’s keen interest in entering negotiations. Abe himself, however, has indicated he well might pursue Japanese entry into at least negotiations.

5. Noda’s bad luck. It’s hard to see, even looking back to his appointment as prime minister in September 2011, a scenario where Noda could have saved the party from Sunday’s electoral oblivion, because so many events have been outside of his control.

It was Ichirō Ozawa (小沢 一郎) who made a decision to break away from the DPJ in July 2012, take 48 leftist Diet members and form the People’s Life First Party (国民の生活が第一 Kokumin no Seikatsu ga Daiichi), thereby depriving the DPJ of its absolute majority.

It was Shintaro Ishihara, then governor of Tokyo, who initially set off the crisis with the PRC over the Senkaku islands when he originally proposed buying them, giving Noda another headache when Noda’s federal government stepping in to outbid Ishihara’s Tokyo government.

Noda (pictured right) also found himself dealing with a public increasingly angry with the Japanese government’s response to the nuclear meltdown at the Fukushima power plant when he pushed forward with nuclear power, despite calls to phase it out by the 2030s.

Finally, although the LDP ultimately provided Noda’s caucus the support it needed to pass the consumption tax hike shortly before Noda dismissed the parliament, the tax’s unpopularity also certainly hurt the DPJ on Sunday. But Japanese voters also seemed ready to punish Noda for the flaws of his two predecessors, including the failure of the Hatoyama government to end or even limit the U.S. military presence in Okinawa, the inability to provide the stability that eluded the LDP after Koizumi, and the failure to avoid the kinds of corruption that the DPJ pledged to end with a new approach to government.

6. Hashimoto’s (and Ishihara’s) ascendancy. Given the charm with which the relatively young Tōru Hashimoto (橋下徹) emerged onto the Japanese political scene, first as governor of Osaka prefecture from 2008 to 2011 and now as Osaka mayor, his economically liberal Japan Restoration Party (日本維新の会, Nippon Ishin no Kai) was originally a vehicle for ongoing calls for a more federalist approach to Japanese economic policy with greater devolution of decision-making power to the cities and prefectures.

Japan Restoration, however, took on a much more nationalist and conservative edge when Shintaro Ishihara (石原慎太郎), former Tokyo governor (from 1999 to 2012), among Japan’s most outspokenly nationalist right-wing politicians, merged his nationalist Sunrise Party (太陽の党, Taiyō no Tō) into Hashimoto’s Osaka-based party.

Ishihara immediately became the leader of the hastily merged party, and his strident views on Japan’s military and his pro-nuclear energy stance, quickly became the party’s policies, despite Hashimoto’s anti-nuclear position, giving the party a somewhat haphazard and schizophrenic nature throughout the campaign. The party originally said it would back Abe for prime minister Monday before later stating that it would instead back Ishihara. Unlike New Kōmeitō, it is not expected to join any formal coalition with the LDP, but it may back Abe’s government with respect to any moves to revise Article 9.

Although the party hoped to win over 100 seats in Sunday’s election, it still managed to win 54 seats — just three less than the DPJ. Indeed, on the proportional representation vote, Japan Restoration won 20.50%, enough to win second place (see chart above).

But the strong third-party presence in Sunday’s election means that in many constituencies, all of the alternatives to the LDP split the anti-LDP vote, thereby allowing the LDP to win by a plurality of the votes. The Asahi Shimbun reports that in 12 constituencies with five-party races, the LDP won all 12 seats; in 69 constituencies with four-party races, the LDP won 62 to just four for the DPJ and three for third parties (including two for Japan Restoration); finally, in the 127 constituencies with three-party races, the LDP won 97, the DPJ and its allies won 17 and third parties won just 12 (including nine for the Japan Restoration).

Hashimoto (pictured above right, with Ishihara, left) again called on Monday for a larger alliance with Your Party (みんなの党, Minna no Tō) — a center-right party devoted to liberal economic policies and lower taxes that won 18 seats on Sunday. A merged party with Your Party would feature 72 seats, making it the largest opposition in the lower house of the Diet. Your Party has also pushed a more reformist position to make Japan’s government more democratic; it refused to join Hashimoto’s original Japan Restoration Party because of its opposition to Ishihara’s nationalist positions.

7. Tokyo. In Tokyo, which also held a gubernatorial election on Sunday, Naoki Inose (猪瀬 直樹), an Ishihara protégé, easily won against the rest of the nine-candidate field on a platform of essentially continuing Ishihara’s agenda.

That agenda includes a bid for the 2020 Summer Olympics and the integration of Tokyo’s dual subway systems. Inose (pictured left), a prize-winning author, became a vice governor of Tokyo in 2007 under Ishihara, and became acting governor when Ishihara resigned earlier this autumn to pursue a return to the Diet.

Inose’s first task will be to develop a political persona separate than that of Ishihara’s, but for now, his win is a major boost for Ishihara.

Hashimoto and Ishihara are essentially competing to become the head of the new party going forward, however, and the fact that Inose won what was essentially a referendum on Ishihara’s performance as governor will help solidify Ishihara’s political power. Furthermore, Hashimoto still has a day job as Osaka mayor, while Ishihara can tend to business in the Diet. As such, it sure appears that Ishihara will have the initial upper hand over Hashimoto. That could change, of course, if Hashimoto manages to merge the party with Your Party. Certainly, the party will have much work to do in smoothing over its Janus-faced nature before next summer’s upper house elections, where it could have a legitimate shot to win.

8. Ozawa’s decline. Ichirō Ozawa, for better or worse, once the key power-broker in Japanese politics — the ‘Shadow Shogun’ so often poised just behind the scenes — has seen his power vastly diminished, maybe for good.

When he stormed out of the DPJ in July 2012, it wasn’t a surprise — he launched a high-profile and debilitating campaign against Naoto Kan (菅 直人), challenging the then-prime minister for the DPJ leadership in 2010. He lost, but the damage was largely done when he refused to back Kan’s plans — and then Noda’s plans — to increase the Japanese consumption tax.

Ozawa (pictured right) similarly stormed out of the LDP in 1993 and after heading a string of parties in the 1990s, ultimately joined the DPJ in 2003 — he rose to become president of the DPJ from 2006 to 2008, and he exercised an influential role in the Hatoyama government in 2009-10. Corruption allegations, least of which those surrounding Ozawa, led in part to the Hatoyama government’s fall in 2010.

In advance of the elections, however, Ozawa had merged his People’s First Party into the Tomorrow Party of Japan (日本未来の党, Nippon Mirai no Tō), which had itself been founded by the governor of Shina prefecture, Yukiko Kada (嘉田 由紀子), running on a relatively populist platform of opposition to nuclear power and against the sales tax hike.

The merged party finished far behind, with just nine seats total. In the proportional representation vote, it won just 5.72%, less than Your Party or even the longtime radical left Japanese Communist Party (JCP, or 日本共産党, Nihon Kyōsan-tō).

What it means is that Ozawa, at age 70, is likely washed up as a ‘Shadow Shogun’ in at least the near-term, having burned bridges to both the LDP and the DPJ, although the multiple comebacks of Ishihara, age 80, may well give Ozawa hope that he too can recover.

9. Asō’s return and the LDP’s internal politics. Tarō Asō (麻生 太郎), former foreign minister and prime minister from September 2008 to September 2009, is reported to be returning to government as the next deputy prime minister and finance minister.

Asō (pictured left) is known for relatively more hawkish views on foreign policy, like Abe, and his rumored selection means that Abe is looking to build a cabinet with many veteran and experienced lawmakers, not just allies close to Abe. That’s especially important in Japan, where the LDP at the parliamentary level remains more a constellation of diverse factions than a truly united political party, and it’s notable because Abe’s first premiership fell in 2007 in part because of the corruption allegations surrounding many of his cabinet members.

Bringing together a united cabinet from various factions of the LDP will be especially key for an electorate that has grown tired of revolving-door governments — for instance, Abe has also indicated he will retain the LDP’s secretary general Shigeru Ishiba (石破 茂), a popular figure who lost the earlier leadership contest to Abe in late September. Furthermore, Yamaguchi’s New Kōmeitō, if it enters a formal coalition, as expected, with the LDP, will also likely hold at least one cabinet position.

Asō, known as somewhat of a high roller in Japan, presided over Japan’s government during the worst of the global financial crisis of 2008 and 2009, and he spent much of his premiership engaged in effecting stimulus measures ultimately deemed insufficient to boost the Japanese economy against global headwinds, but will certainly be enthusiastic to implement expansionary fiscal policy once again. Both Asō and Abe come from longtime Japanese political pedigrees — indeed, both of them have grandfathers who once served as prime minister.

10. Naoto Kan’s loss and the future of the DPJ. For the first time, a former prime minister lost his constituency seat — Naoto Kan (pictured below, right), who came to office in June 2010 and was succeeded by Noda in September 2011. Kan will hold onto a seat by benefit of having been on the proportional representation list for the seat. Kan presided over a failed effort to raise Japan’s sales tax, an internal leadership challenge from Ozawa, and losses in the July 2010 elections for the House of Councillors. He was also prime minister during the horrific March 2011 earthquake and tsunami that caused a nuclear meltdown at the Fukushima power plant.

Kan’s embarrassing loss means that he certainly won’t be leading the DPJ into next summer’s elections; certainly Hatoyama and Noda won’t be, either, and Ozawa has fled the scene too. Two of Noda’s key cabinet members, chief cabinet secretary Osamu Fujimura (藤村 修) and outgoing finance minister Koriki Jojima (城島光力) lost their seats on Sunday as well, so thorough was the decimation of the DPJ ranks in the House of Representatives.

There’s not even much assurance that the party will stay together in the wake of its loss, with some right-wing DPJ members already threatening to split from the party to form their own entity.

One candidate that may emerge as the new DPJ leader is Goshi Hosono (細野 豪志), chairman of the party’s Policy Research Committee — at age 41, he’s likely to be seen as a rising star from a new generation of DPJ politicians. Outgoing deputy prime minister Kasuya Okada (岡田 克也) and state minister for national policy Seiji Maehara (前原 誠司) may also run. The DPJ secretary general Azuma Koshiishi (輿石 東), who leads the party caucus in the House of Councillors (where there are now 88 DPJ members, more than in the lower house after Sunday) is likely to play a key role in the DPJ’s future.

11. Nuclear policy. Except for Ishihara, who has remained incredibly pro-nuclear energy, each of the other main parties, including Your Party, the DPJ and the LDP, have backed away from the promotion of nuclear energy. Prior to the 2011 tsunami and Fukushima disaster, Japan was one of the world’s most enthusiastic backers of nuclear power, deriving 30% of its power from nuclear reactors and planning to boost that to 40% (at the top of the scale is France, which derives nearly 80% of its power from nuclear sources; the United States derives around 19%).

All but two of Japan’s 50 nuclear reactors remain idle because of concerns stemming from resistance to future seismic events, though the LDP has called on restarting many of the reactors.

During the campaign, the LDP tried to have it both ways on the nuclear energy issue by calling for an end to Japan’s ‘reliance’ on nuclear power, while not necessarily calling for a ‘zero-nuclear’ Japan like the Tomorrow Party or others, making the LDP’s campaign pledge on energy somewhat more pro-nuclear than the DPJ plan to phase out nuclear energy by the 2030s.

Reading between the lines, it would appear that the LDP believes the status quo ante to be a perfectly fine result for Japan. Even more than its controversial Article 9 revisions, however, no one expects Abe’s government to pick up the nuclear energy issue until after the House of Councillors election.

12. Democracy in East Asia. One of the enduring questions for Japan is whether the broadly competitive two-party system developed over the past decade or so will continue after Sunday’s election. After all, Japan Restoration has nearly as many seats as the DPJ, and the DPJ could soon disintegrate, leaving Japan in essentially a one-party state again, with the LDP firmly in control of government and a handful of smaller parties forever nipping at its heels. If the DPJ does implode, it’s possible, perhaps, for Japan Restoration to absorb some of their more right-wing members and relatively hawkish members, making a bid to become Japan’s main opposition party, maybe in alliance with Your Party. But if the nature of contested democratic elections withers in Japan, it will be a setback for electoral politics for the entire region.

6 thoughts on “Twelve considerations upon the DPJ wipeout in Japan’s legislative elections”