Earlier this month, former British foreign secretary David Miliband penned a letter to the editor for The New York Times.![]()

It had nothing to do with the United Kingdom’s general election on May 7, but instead implored the international community to place greater emphasis on the humanitarian and poverty crises in Afghanistan’s post-occupation rebuilding efforts.

Back in December 2010, however, Miliband had hoped that he would be hitting his stride this month to bring the Labour Party back to power. Instead, he’s the chief executive of the International Rescue Committee, a New-York based NGO, after narrowly losing the Labour leadership to his brother, Ed Miliband.

There were many reasons for David Miliband’s loss: the skepticism of labour unions and the party’s leftists that he would perpetuate the centrist tone of Tony Blair’s ‘New Labour’ platform; the resentment that he never stepped up between 2007 and 2010 to challenge then-prime minister Gordon Brown for the leadership, which may have helped the party to avoid losing power; and the desire to turn the page from the Blair-Brown civil war that increasingly consumed Labour in its third term of government.

After his narrow loss, David never joined his brother’s shadow cabinet and, in April 2013, he left his seat in the British House of Commons to take on the IRC leadership position.

Meanwhile, back in Westminster, Ed Miliband has been Labour Party leader for nearly five years — now much longer than Brown, who had coveted the leadership from his fateful decision in 1994 to support Blair instead of challenging him. From afar, brother David is fully supportive, and there’s a feeling that he left politics altogether out of sense that his lingering presence loomed darkly over Ed Miliband’s leadership.

* * * * *

RELATED: It’s too late for Labour to boot Ed Miliband as leader

* * * * *

It’s been one of the best weeks yet for Ed Miliband. For the first time, British bookies believe that it’s more likely that Miliband will emerge as prime minister after the election, not the incumbent, David Cameron. A teenage girl caused a viral sensation on Twitter when she proudly proclaimed her #milifandom for the prime ministerial hopeful. Though Miliband’s Labour never reclaimed the 10-point advantage that it enjoyed at the nadir of the current Conservative-led government’s tenure, it narrowly leads most seat predictions in a race where no one party seems capable of achieving a majority. But there are still two weeks to go, and it’s worth remembering the #Cleggmania that swept Great Britain during the prior 2010 campaign. There’s a lot of time left for the electorate to shift in either direction.

British politics is full of what-if prime ministers. John Profumo. Denis Healey. Michael Heseltine. Neil Kinnock. John Smith. Kenneth Clarke. Michael Portillo. But none of them resonate quite like David Miliband, whose own younger brother outmaneuvered him to the leadership crown that he almost certainly expected would fall to him.

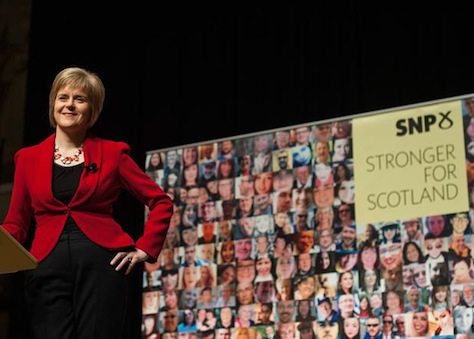

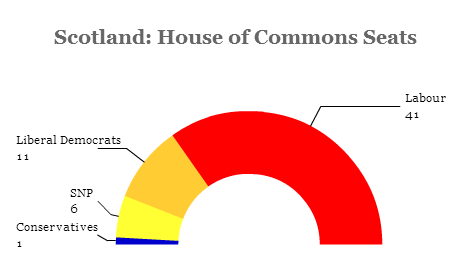

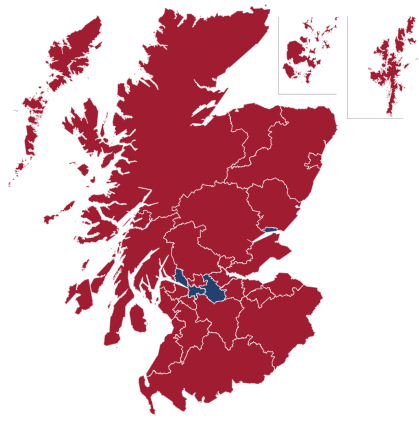

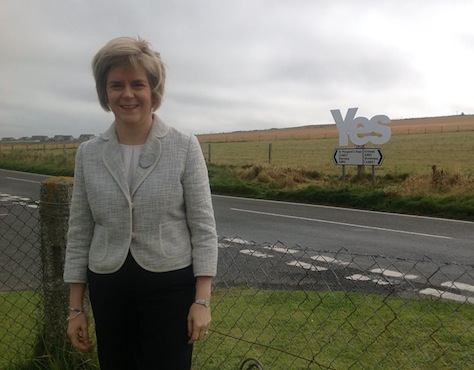

With the Liberal Democrats subdued after joining Cameron in government for the past five years, it seems unlikely that anyone will command the 326-majority in the House of Commons without the support of the pro-independence Scottish National Party (SNP), which is forecast to win almost all of Scotland’s 59 constituencies. Scottish first minister Nicola Sturgeon has made it clear, nonetheless, that she’ll back a broad left-wing government under Miliband and under no circumstances a renewed Tory mandate.

In two weeks’ time, unless the campaign drastically changes, Ed Miliband will be the newest resident of 10 Downing Street. It would be to his credit to coax his older brother back into politics to finish the work he began as foreign minister — it’s not difficult or unprecedented to arrange a by-election in a safe constituency.

Yet there’s still a nagging feeling about Ed Miliband’s leadership. Forget that, so many years ago, it was David Miliband who narrowly won more votes than Ed among the parliamentary Labour caucus and among party voters (Ed narrowly defeated David with stronger support among unions and interest groups that comprised the third group of voters in the tripartite electorate in 2010’s contest). Notwithstanding what the bookies say, Cameron still gets higher marks than Miliband in personal approval ratings, though that gap has narrowed throughout the race. The sudden #milifandom moment aside, Miliband remains in the eyes of many British voters a geeky technocrat with none of the showmanship of Margaret Thatcher or Tony Blair nor Gordon Brown’s sense of history nor John Major’s happy-warrior statesmanship.

He may become prime minister after May 7, but not because of a groundswell of support among the British electorate for an Ed Miliband premiership. It’s too soon to tell if a Labour minority government propped up by the SNP will prove a poisoned chalice. Throughout the campaign, it’s been Sturgeon, not Miliband, savaging the budget cuts of the Tory/Lib Dem government of the past five years. Miliband, instead, curiously focused his campaign’s efforts on more funding for the National Health Service — it’s not an entirely original basis for a center-left platform. After all, the NHS survived the market-happy years of the Thatcher government, and it will survive the ever-so-gentle austerity of a second Cameron term.

But it’s tantalizing to wonder whether David Miliband, had he defeated his brother for the leadership in 2010, would have pushed Labour into striking distance of a majority government. Certainly, even today, he has more gravitas and charisma than anyone else on Labour’s front benches. That includes his brother, but it also includes other potential leaders, including shadow home secretary Yvette Cooper, the pugnacious Brownite shadow chancellor Ed Balls (Cooper’s husband) and health secretary Andy Burnham.

If there’s a turn in the polls, and Cameron ekes out reelection, David Miliband would stand a good shot of winning the leadership against Balls, Cooper, Burnham or just about anyone in Labour today.

Even if Brits are starting to warm to geeky younger brother Ed as a potential prime minister, it’s taken more than four years for him to get to this point. A year ago, the British press was savaging him for not knowing how to eat a proper bacon sandwich, and as recently as last autumn, Labour sources were musing openly about replacing him as leader.

David Miliband would have instantly become prime-minister-in-waiting from the first day of his leadership, and he would have done so with the warm-hearted support of Blair and the only living generation of Labour officials who have held power, officials who have only begrudgingly supported Ed Miliband. It’s not outrageous to believe that David Miliband would have been such a compelling opposition leader that he could have pressured the Cameron-led government into a no-confidence vote, toppling the coalition before the end of its five-year term.

You can’t prove a negative, of course, so we’ll never know. But it’s not difficult to imagine that the #milifandom would have started earlier with much more fanfare had the other brother won.