Whatever the Jakarta gubernatorial election portends for Indonesian president Joko Widodo’s reelection chances in 2019, it points perhaps to a nastier fight for the presidency and, more generally, in Indonesian politics in the future.![]()

![]()

While official results still aren’t available, early counts made clear that Anies Baswedan, backed by both nationalist elites and a growing hardline Islamist movement, unseated Jokowi’s successor as Jakarta governor, Basuki Tjahaja Purnama (known by his nickname, ‘Ahok’) by a far wider margin than expected. A Christian of Chinese descent. Ahok, who ran on Jokowi’s 2012 ticket, took over as governor when Jokowi won the Indonesian presidency in 2014.

Ahok was never quite as popular as Jokowi, and in Indonesian politics, where alliances can shift overnight, it’s too strong to suggest that Ahok’s defeat predicts trouble for Jokowi, who is looking to reelection in mid-2019. But the harsh tone of an election that took on racial and religious tones in a country that prides itself on tolerance and coexistence is an ominous sign.

Jakarta, home to over 10 million people, is one of the world’s 15 most-populous cities and, by far, the largest city in Indonesia. As governor, Ahok perhaps has an even more impressive record in three years than Jokowi had in two. With few ties to the longstanding ruling class, Ahok was an anti-corruption crusader whose brash actions to clean up Jakarta’s canals, reduce pollution and demolish some of the worst slums in the city rankled many of its residents, especially its poorer ones.

Far more damning to Ahok, however, was a concerted effort last year by radical Islamists to drag his name through the mud.

As the campaign wore on, however, it became clear that Ahok’s political rivals were happy to benefit from angst over his status a double minority and, especially, as a non-Muslim. At the end of last year, the hardline Islamic Defenders Front (FPI) organized a series of protests against Ahok that severely dented his popularity, especially among Muslims. The campaign introduced a new and far more divisive edge to Indonesian politics, which has not traditionally revolved primarily around race or religion. Ahok could still be imprisoned for up to five years on charges of violating blasphemy laws — what Ahok’s supporters believe a ridiculous and politically motivated charge. The outgoing governor is accused of insulting the Quran by quoting a Quranic verse last September in his reelection bid.

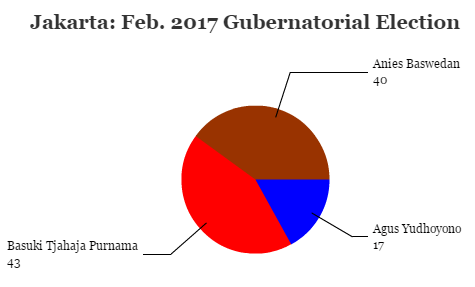

In an earlier round of voting on February 15, Ahok narrowly led Anies and Agus Harimurti Yudhoyono, the son of Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, Jokowi’s predecessor as president, but failed to secure the majority support necessary to avoid a runoff.

Anies, until recently, was a moderate university administrator, and he even supported Jokowi in 2014, serving as a spokesman for Jokowi’s campaign. A student activist during the Suharto regime and, in more recent times the rector of Paramadina University, Anies also served as Jokowi’s minister of education and culture, leaving the cabinet in a July 2016 reshuffle (a reshuffle that, controversially, brought Wiranto, a former Suharto general accused of human rights violations in East Timor in the late 1990s, into Jokowi’s cabinet.)

Though Jokowi’s reshuffle, in part, helped solidify alliances for his 2019 reelection bid and reduced his dependence on his own party, the Partai Demokrasi Indonesia Perjuangan (PDI-P, Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle) and its longtime leader, former president Megawati Sukaroputri (who once referred to the president dismissively as a ‘functionary’). But the reshuffle also sent Anies in search of a new job and new political patrons. While Anies has always been a moderate Muslim, he had no problem embracing the harsh tactics of the FDI to his benefit in the Jakarta campaign.

More central among Anies’s new supporters is Prabowo Subianto, the runner-up in the 2014 presidential election. Prabowo, who comes from an elite family in Javanese politics, and and who heads the nationalist Partai Gerakan Indonesia Raya (Gerindra, Great Indonesia Movement Party), now has some momentum to mount a rerun against Jokowi in 2019. Indeed, businessman Sandiaga Uno, who only recently entered politics in 2015 as a top Prabowo protege, smoothed the Anies-Prabowo alliance, as it was his idea to recruit Anies for Jakarta governor, and Sandiaga joined Anies’s ticket as his running mate.

Also among Anies’s new supporters: Aburizal Bakrie, one of thew wealthiest businessmen in Indonesia and, until the end of 2015, the leader of Partai Golongan Karya (Golkar, Party of the Functional Groups). Golkar, which originated as Indonesia’s governing party in the Suharto era, has in the post-Suharto era embraced market-based reforms and pro-business policies. But it has split into two factions since Jokowi’s election — one that opposes Jokowi (personified by Bakrie) and one that supports Jokowi (personified by Golkar’s current leader Agung Laksono). Jokowi, after all, ran for president in 2014 on a ticket with Golkar’s 2009 presidential candidate, Jusuf Kalla.

Yudhoyono’s party, the Partai Demokrat (Democratic Party), which was formed in 2004 solely as a vehicle to advance the Yudhoyono presidency, and which seems to be collapsing now that Yudhoyono has essentially retired from political life, has remained neutral between the two coalitions. His son, who placed far behind Ahok and Anies in the Jakarta election’s first round, refused to endorse either candidate for governor.

While Golkar now supports Jokowi for 2019 reelection, the united force of Prabowo’s Gerindra, Bakrie’s Golkar splinter group, a rising tide of Indonesian Islamists and Anies, now a force in his own right as Jakarta’s governor, will present a potent challenge to Jokowi, who comes from outside the traditional political elite, and who has struggled to consolidate power.

With eyes turned now firmly to 2019, Jokowi remains broadly popular with the electorate, despite economic malaise and a collapse in the value of the rupiah since taking office. His international fans, who looked to Jokowi as a kind of Indonesian version of Barack Obama, have been dismayed by his support for the death penalty for drug dealers as a solution to Indonesia’s drug abuse problem. Nevertheless, Jokowi has implemented steps to liberalize the sluggish Indonesian economy, sometimes putting him at odds with leaders of his own PDI-P. He scrapped fuel subsidies almost immediately after taking office and introduced last summer a tax amnesty program. It coincided with the re-appointment of Sri Mulyani Indrawati, a lauded Indonesian economist and former World Bank managing director, as Jokowi’s new finance minister. Sri Mulyani held the same position from 2005 to 2010 and is widely respected for steering the economy through the global financial crisis in the Yudhoyono era. As noted, Jokowi has enhanced his legislative majority by bringing Golkar fully into his coalition and by reaching out to many of the smaller Islamist parties. Subject to ugly rumors about his own ethnic background and religion in his 2014 election, Jokowi has increasingly played up his own Muslim faith as president.

Ahok, who realized Jokowi was a stronger gubernatorial candidate in 2012, forfeited his own plans to run on Jokowi’s ticket, was never in the same league of political rockstar as Jokowi (even aside from his Chinese background and Christian faith).

Jakarta, too, has always been something of a bellwether for the country in general — in the 2014 presidential election, Jokowi won just 53.1% of the vote in Jakarta, while Prabowo won 46.9%, almost mirroring the national results exactly (53.15% to 46.85%).

So it’s far too soon to rule out Jokowi’s chances in two years’ time.

Nevertheless, well before Donald Trump’s emergence on the world stage, Prabowo was part of the vanguard of a new nationalist populism, and that will only help him as he appears to prepare for one last presidential run in 2019 in a far Trumpier world. As the two dominant coalitions prepare for that race, however, both sides will take note of the brutish and incendiary tone of the 2017 Jakarta campaign — and both sides will take note that the religious and ethnic mudslinging worked.

Your pie chart shows Ahok winning??