Whatever the Jakarta gubernatorial election portends for Indonesian president Joko Widodo’s reelection chances in 2019, it points perhaps to a nastier fight for the presidency and, more generally, in Indonesian politics in the future.![]()

![]()

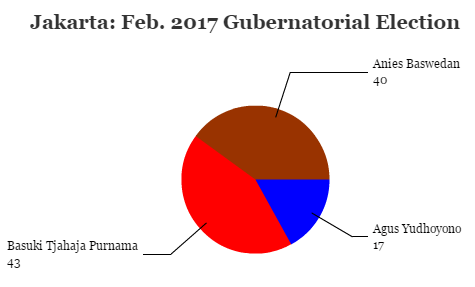

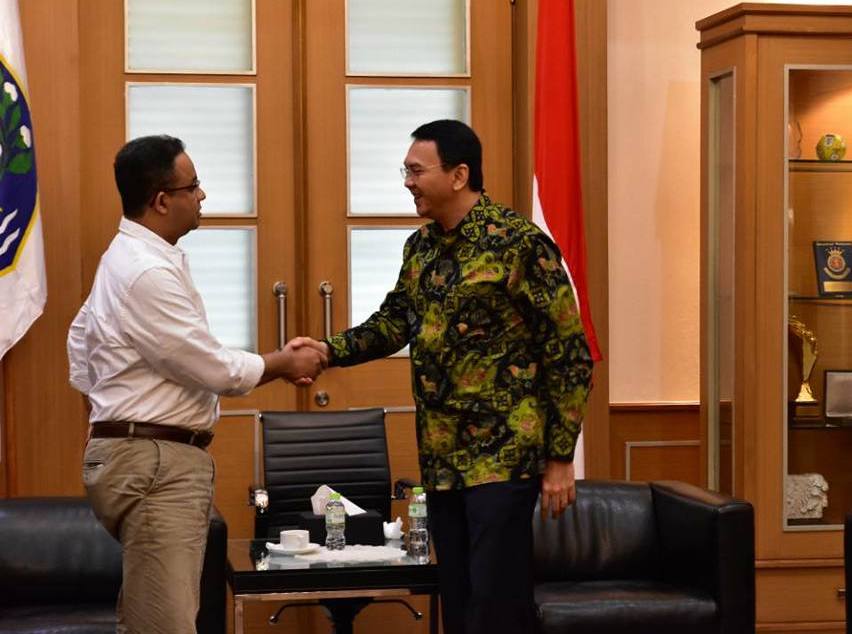

While official results still aren’t available, early counts made clear that Anies Baswedan, backed by both nationalist elites and a growing hardline Islamist movement, unseated Jokowi’s successor as Jakarta governor, Basuki Tjahaja Purnama (known by his nickname, ‘Ahok’) by a far wider margin than expected. A Christian of Chinese descent. Ahok, who ran on Jokowi’s 2012 ticket, took over as governor when Jokowi won the Indonesian presidency in 2014.

Ahok was never quite as popular as Jokowi, and in Indonesian politics, where alliances can shift overnight, it’s too strong to suggest that Ahok’s defeat predicts trouble for Jokowi, who is looking to reelection in mid-2019. But the harsh tone of an election that took on racial and religious tones in a country that prides itself on tolerance and coexistence is an ominous sign.

Jakarta, home to over 10 million people, is one of the world’s 15 most-populous cities and, by far, the largest city in Indonesia. As governor, Ahok perhaps has an even more impressive record in three years than Jokowi had in two. With few ties to the longstanding ruling class, Ahok was an anti-corruption crusader whose brash actions to clean up Jakarta’s canals, reduce pollution and demolish some of the worst slums in the city rankled many of its residents, especially its poorer ones.

Far more damning to Ahok, however, was a concerted effort last year by radical Islamists to drag his name through the mud.

As the campaign wore on, however, it became clear that Ahok’s political rivals were happy to benefit from angst over his status a double minority and, especially, as a non-Muslim. At the end of last year, the hardline Islamic Defenders Front (FPI) organized a series of protests against Ahok that severely dented his popularity, especially among Muslims. The campaign introduced a new and far more divisive edge to Indonesian politics, which has not traditionally revolved primarily around race or religion. Ahok could still be imprisoned for up to five years on charges of violating blasphemy laws — what Ahok’s supporters believe a ridiculous and politically motivated charge. The outgoing governor is accused of insulting the Quran by quoting a Quranic verse last September in his reelection bid.

In an earlier round of voting on February 15, Ahok narrowly led Anies and Agus Harimurti Yudhoyono, the son of Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, Jokowi’s predecessor as president, but failed to secure the majority support necessary to avoid a runoff. Continue reading As Jokowi looks to 2019 reelection, rivals deal a blow by taking Jakarta