Last Thursday, the United States-Indonesia Society and the International Republican Institute held a briefing of data from R. R. William Liddle, a professor emeritus of political science at The Ohio State University and one of the leading US experts on Indonesian politics, government and culture. ![]()

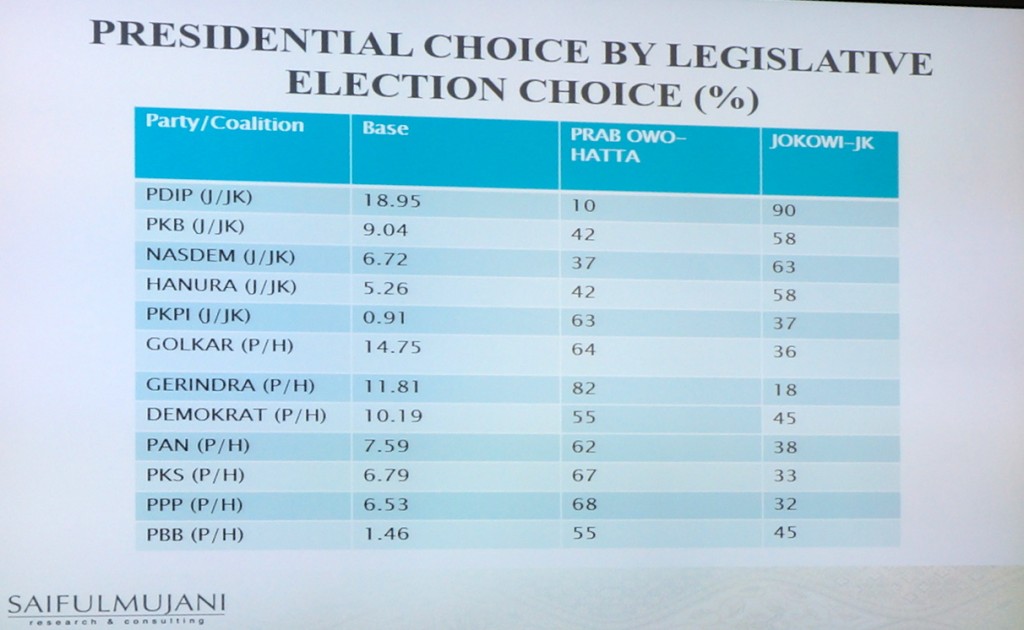

Dr. Liddle brought with him a compelling set of exit polling data conducted by Saiful Mujani, a Jakarta-based research and consulting firm.

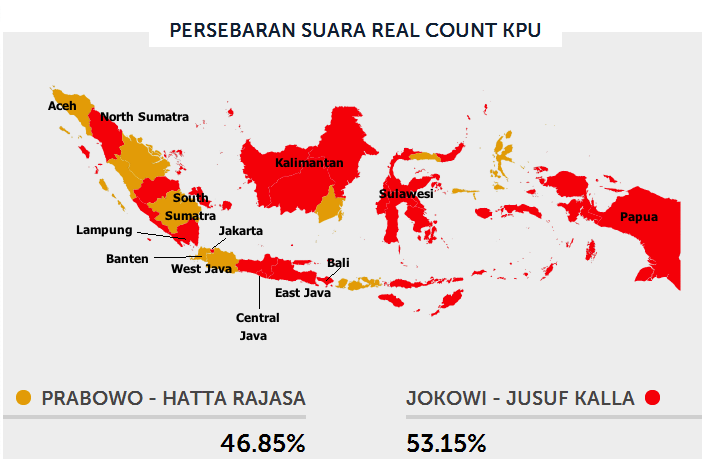

The data provided the strongest narrative details yet for how Jakarta governor Joko Wododo (‘Jokowi’) effectively outpaced former general Prabowo Subianto in what was Indonesia’s most fiercely and closely contested election since the introduction of direct voting for the presidency in 2004.

For example, it may be counterintuitive, but younger, urban voters appeared to prefer, by a slight margin, Prabowo to Jokowi. After all the talk of Jokowi as the younger candidate of hope and of reform, the ‘Barack Obama’ of Indonesia after his meteoric rise from Solo mayor to Jakarta governor to, now, president-elect, it isn’t necessarily intuitive that Jokowi edged his way to the Indonesian presidency on the support of relatively poorer, rural and older voters.

Voters by age

Voters under 21 years old supported Jokowi by a margin of just 53% to 47%, but voters over 55 supported Prabowo by a margin of 59% to 41%. Though you might expect younger voters to be most enthusiastic for a relatively young, modern president, they opted for Prabowo, nine years Jokowi’s senior.

One possibility is that younger voters don’t entirely remember Indonesia’s authoritarian age, but older voters remember only too well the human rights abuses of Suharto’s three-decade reign and, most especially, the economic pain of the financial crisis of 1997-99 that brought down Suharto’s ‘New Order.’ Given Prabowo’s ties to the regime — he was a top Suharto-era general and he used to be married to Suharto’s daughter — older voters might have been warier about supporting the former general, given his checkered past.

Rural and urban voters and voters by class

Rural voters preferred Jokowi by a margin of 56% to 44%, but Prabowo narrowly won urban voters by a margin of 51% to 49%. The data also showed that ‘white-collar’ voters supported Prabowo by 55% to 45%, while ‘blue-collar’ voters backed Jokowi by 54% to 46%.

Again, it’s a fascinating turn, considering Prabowo’s emphasis on economic nationalism that, in most countries, finds a greater audience among the least economically powerful. Wall Street bankers and investment attorneys in the United States, for example, are much less likely to support protectionist policies than, say, blue-collar ironworkers or manufacturers who acutely feel the sting of global competition.

As Liddle noted, there might be several reasons for Prabowo’s apparent strength among educated, successful, cosmopolitan Indonesians. One of them is the way that Jokowi framed himself as a ‘common man’ candidate — not a president who, like Prabowo, comes from the Indonesian elite, educated in international schools and has exquisite English-language skills. Prabowo, throughout the campaign, effectively demonstrated that his much greater exposure to the United States and the wider world, and many cosmopolitan voters found that quality reassuring.

Voters by religion

Islamic voters narrowly favored Prabowo by a margin of 51% to 49%, while non-Islamic voters overwhelmingly backed Jokowi by an 80% to 20% margin. That’s not surprising, given that three of the four major Islamist parties backed Prabowo and that his running mate, Hatta Rajasa, former coordinating minister for economics, is the leader of the Islamist Partai Amanat Nasional (PAN, National Mandate Party). It’s also not surprising in light of the whispering campaign that Jokowi is secretly Christian. The predominantly Hindu island of Bali, for example, has always been a stronghold for Jokowi’s party, the Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P, Partai Demokrasi Indonesia Perjuangan), and Jokowi did particularly well in predominantly Christian areas, such as Papua. It also explains why Prabowo won Indonesia’s most populous province, West Java, home to some of Indonesia’s most conservative Muslims — with 46.3 million people, West Java contains nearly 19% of the country’s population.

The Javanese-Sundanese split

The data indicate that Jokowi triumphed among the Javanese by a margin of 56% to 44%, while Prabowo won the Sundanese by a margin of 80% to 20%. That explains why, despite Prabowo’s West Java breakthrough, with a heavy Sunda population, Jokowi narrowly won Jakarta (9.6 million) and East Java (37.5 million), and he racked up an even more solid victory in Yogyakarta (3.5 million) and Central Java (32.4 million), the traditional Javanese homeland. Among non-Javanese and non-Sundanese voters, Jokowi won by a margin of 53% to 47%. While Prabowo generally won more provinces in Sumatra, for example, Jokowi won the most populous province, North Sumatra (13 million), and Jokowi’s running mate Jusuf Kalla may have helped Jokowi win much of the island of Sulawesi.

The most interesting finding of the survey, though? Continue reading Indonesia post-mortem: why young, cosmopolitan voters chose Prabowo