Irish voters delight in contrarianism.![]()

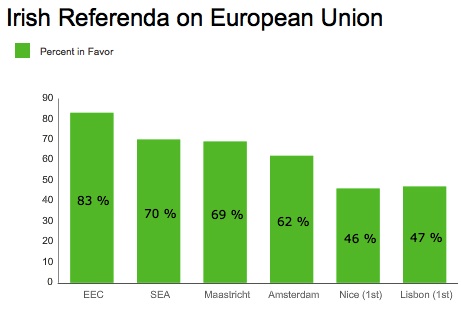

When Irish voters were supposed to endorse the Treaty of Nice in 2001, they rejected it instead. After nine months of renegotiation with the European Union to secure recognition of Ireland’s traditional military neutrality, Dublin held a second referendum and Irish voters adopted the revised Nice treaty. Irish voters did the same thing in June 2008, when they rejected the Treaty of Lisbon by an equally narrow margin (again, Dublin set about renegotiating and held a successful referendum shortly thereafter).

When Irish voters, suffering under severe budget cuts and tax increases, may have had a gripe with last year’s European ‘fiscal compact’ (not a treaty, in the formal sense, because of the United Kingdom’s veto), they instead approved the fiscal compact by a wide margin in the June 2012 referendum.

In Sunday’s referendum, Ireland’s stubborn voters were expected to vote to abolish the Seanad Éireann (Irish senate), the upper house of the Oireachtas, Ireland’s parliament, on the promise of a future with fewer politicians instead of more.

Political leaders across all lines — the Irish left, the Irish center-right and even Irish nationalists — supported moving to a unicameral system to cut up to $20 million in annual costs and to eliminate a chamber that’s largely seen as unrepresentative, undemocratic and wasteful, while using the opportunity to register disgust with a political elite that remains unpopular in the wake of a sovereign debt crisis, the failure of Irish banks, and a humiliating European bailout that has imposed a new era of austerity in a country that, only a decade ago, was known as the ‘Celtic Tiger’ for its surging economy.

But perhaps the Irish electorate decided to register its contrarianism at the very notion of being perceived as anti-politician contrarians.

For whatever reason, not enough Irish voters elected to abolish the Seanad, and the October 4 referendum was defeated by a narrow margin of 51.7% voting ‘No,’ and just 48.3% voting ‘Yes.’

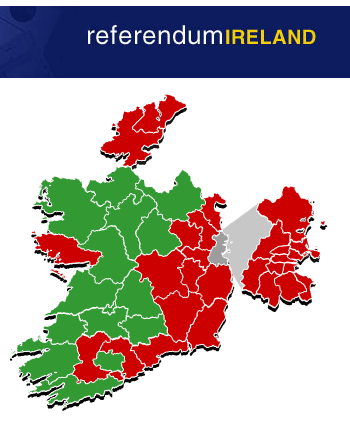

The result broke down on largely regional lines. Voters in Munster and Connacht in the west of the country largely voted to abolish the Irish senate, while the northern state of Ulster and the eastern state of Leinster (including all of the constituencies in Dublin) voted to retain the senate. In particular, Ulster voters worried that the elimination of the Irish senate would also eliminate the one forum where Northern Irish voices have been historically heard within the government of the Republic of Ireland.

The result left the Taoiseach (Ireland’s prime minster), Enda Kenny, with perhaps the biggest defeat since taking power in March 2011. Kenny campaigned on the promise of eliminating the Irish senate, and the referendum fulfills a promise to bring the issue to a direct referendum. But as Kenny said following the result: ‘Sometimes in politics you get a wallop.’

The defeat is another warning sign of the growing unpopularity of Kenny’s government — though voters blamed Fianna Fáil for the initial Irish banking crisis and its aftermath, they seem to be holding Fine Gael responsible for the austerity that’s followed since the 2011 elections.

A recent October 1 RTE poll showed that Kenny’s liberal center-right Fine Gael has plummeted to 26% support (after winning 36.1% in the last election), while its coalition partner, the progressive Labour Party wins just 6% support, the lowest level in decades (after winning 19.4% in 2011). Though the conservative center-right Fianna Fáil has regained some ground at 22% (up from 17.4% in 2011), the real winner is the Irish nationalist party Sinn Féin, which polled 23% support (up from 9.9% in 2011).

Among the supporters of abolishing the Irish senate were Fine Gael, Labour, Sinn Féin and Ireland’s Socialist Party. Politically speaking, the result was a victory for Ireland’s most successful post-independence party, the conservative center-right Fianna Fáil, which suffered a historical loss in the 2011 election. Fianna Fáil campaigned against eliminating the Irish senate in favor of reforming it, arguing that it served as a necessary watchdog against poor government. Kenny had received criticism prior to the vote for refusing to debate Fianna Fáil leader Micheál Martin, and those criticisms amplified in the aftermath of the referendum’s defeat.

It’s also a victory for many of Ireland’s longtime independent senators, some of whom are incredibly colorful and thoughtful figures, including David Norris (pictured above kissing a supporter), a scholar of James Joyce and Ireland’s first major openly gay presidential candidate. Continue reading Irish vote to retain the Seanad deals blow to Kenny, who pledges parliamentary reform instead