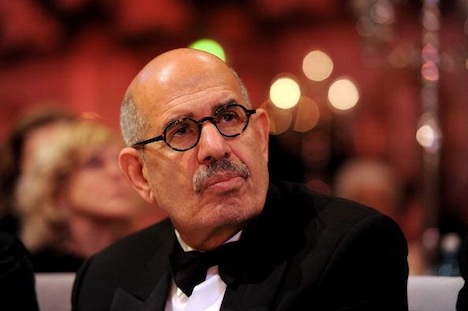

UPDATE: Egyptian officials are now distancing themselves from earlier reports that Mohamed ElBaradei will be Egypt’s next prime minister — that doesn’t incredibly change the analysis, though. ElBaradei’s ties to the West, not to mention the other drawbacks mentioned below, help us understand why Egypt’s new military-backed government may have had second thoughts about ElBaradei, especially if they are hoping to bring Salafist Al-Nour Party leaders into the fold.

* * * *

Mohamed ElBaradei is set to become Egypt’s interim prime minister just four days after Mohammed Morsi was deposed as from the Egyptian presidency by the country’s armed forces.

ElBaradei, the former director general of the International Atomic Energy Agency, is a well-known figure whose international credibility runs far deeper than that of newly-installed interim president Adly Mansour, formerly the chief justice of the Egyptian constitutional court. His selection as prime minister will bring instant gravitas to the emerging post-Morsi regime in Egypt, at least vis-à-vis the rest of the world.

But deploying ElBaradei into power is not risk-free — for either the new government or for ElBaradei’s reputation.

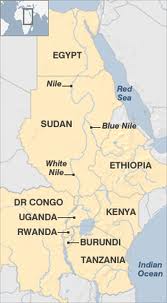

The danger is that his selection won’t be enough to ameliorate the governance crisis that has now accelerated with the Egyptian military’s decision to remove Morsi. After all, though Morsi’s government had few allies after its troubled year in office, it’s hard to believe that the Muslim Brotherhood still doesn’t command the largest bloc of supporters within Egypt, and their wrath at the military’s turn against the Muslim Brotherhood may not be soothed by the appointment of any caretaker, no matter his seniority or even-handedness. ElBaradei’s appointment comes just a day after pro-Morsi supporters of the Muslim Brotherhood staged a day of protest — the ‘Friday of rejection’ — demanding the return of Morsi to the presidency that met with tense, sometimes violent, resistance from the Egyptian military. It’s too early to predict that Egypt is descending into a kind of civil war — despite a troubling lynching of four Shi’a Muslims last month, the largely Sunni Egypt doesn’t really feature strong Sunni-Shi’a schisms that have propelled sectarian violence more recently in countries like Iraq and Syria, and most Egyptians, even its more conservative Islamists, hold the military in high regard, for now at least. But there’s no guarantee that ElBaradei can keep political violence from spiraling further out of control, propelling ever more turmoil to Egyptian industry, trade and tourism.

Even if no one will miss the ineptitude of the Morsi government, ElBaradei’s new power doesn’t come imbued with much of a mandate. Though Egypt’s post-Mubarak transition was troubled from its inception, the successful conduct of free and fair presidential elections last summer was a key milestone on Egypt’s road toward a more democratic state. While it’s true that the anti-Morsi protests had ballooned to a size even larger than those against Mubarak in February 2011, the more relevant factor is that Mubarak was never elected in a free election the way that Morsi was only a year ago. So while political scientists debate whether last week’s events amounted to a coup (spoiler: yes, of course it was a coup, even if the U.S. administration doesn’t use the word ‘coup’), ElBaradei and his military supporters will come to power having undermined the most visible democratic credential that Egyptians could boast since the Arab Spring began.

By contrast, though French president François Hollande remains incredibly unpopular after just one year into a five-year term, no one seriously thinks the French military is set to remove him from office to install a center-right president in France. Moreover, ElBaradei will become Egypt’s new leader after having pulled out of last year’s presidential race, and it was not entirely clear that ElBaradei would have won in any event. But it would have been better for the country today if ElBaradei had remained in the race to make a full-throated case for a secular, liberal democratic Egypt and to bring the fight to Morsi on the basis of the merits of his own ideas, not on the coattails of the military’s guns.

Unlike former foreign minister and Arab Council secretary-general Amr Moussa and former air force chief Ahmed Shafiq, ElBaradei is not tainted as felool — the ‘remnants’ of the government that Hosni Mubarak led from the 1980s until 2011. But as the Tamarod (‘Rebellion’) movement has gathered steam in its efforts to oust Morsi, ElBaradei has managed to unite a disparate coalition of anti-Morsi interests, including Moussa, much of the former military establishment, elements of the so-called ‘deep state’ and supporters of former presidential candidate Hamdeen Sabahi, whose leftist, Nasser-style nationalism nearly vaulted him into last June’s presidential runoff. If Monsour, ElBaradei and the new interim government succeed in organizing a new presidential election, Sabahi would certainly be the frontrunner to win it (unless ElBaradei himself runs, though he’s said he’s not interested in the presidency for himself).

As ElBaradei has noted in the days leading up to and following Morsi’s forced removal, the Morsi presidency was far from perfect — ElBaradei had routinely accused Morsi of becoming a ‘pharaoh’ in office, and he mocked Morsi’s Islamist agenda by noting acidly that ‘you can’t eat sharia.’ Though Morsi won only a narrow victory last June over Shafiq, he triumphed by assembling a broader coalition that transcended his own Muslim Brotherhood supporters, and, in recognition of that reality, Morsi initially called for a broad inclusion of diverse views in formulating policies in office. One of his first steps in August 2012, in firing longtime army chief and defense minister Field Marshal Hussein Tantawi, and replacing him with Abdel-Fattah El-Sisi, was an incredibly successful masterstroke, temporarily at least, in marrying the political interests of the Muslim Brotherhood and the Egyptian military. Ironically, it was El-Sisi, who owed his position as commander-in-chief of the Egyptian armed forces to Morsi, who green-lighted the action that toppled Morsi.

But as Bassem Sabry explained in illuminating detail on Thursday in Al-Monitor, the clear point at which Morsi lost control over the country was his ill-fated decision last November to push through a vote on the country’s new constitution. Continue reading ElBaradei set to become interim Egyptian prime minister in post-Morsi gamble for ‘reset’