I’m not running for the leadership of the Labour Party in 2015. But it seems like hugging Peter Mandelson — figuratively and nearly literally — on the eve of the leadership campaign is an odd step for Chuka Umunna (pictured above, left, with Mandelson), the shadow business secretary and the youngest of several members of the ‘next generation’ of Labour’s most impressive rising stars.![]()

Though he hasn’t formally announced anything, Umunna is doing everything to signal that he will seek the Labour leadership, including an op-ed in The Guardian on Saturday that serves as a laundry list of Umunna’s priorities as Labour leader:

First, we spoke to our core voters but not to aspirational, middle-class ones. We talked about the bottom and top of society, about the minimum wage and zero-hour contracts, about mansions and non-doms. But we had too little to say to the majority of people in the middle… [and] we talked too little about those creating wealth and doing the right thing.

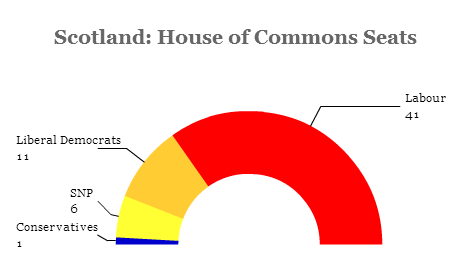

Ed Miliband’s resignation on Friday, in the wake of Labour’s most disappointing election result in a quarter-century, has opened the way not only for a robust leadership contest, but for a free-for-all of second-guessing about Miliband’s vision for Labour in the year leading up to last week’s election.

Liz Kendall, the 43-year-old shadow minister for care and older people, was the first to announce her candidacy for the leadership; shadow justice minister David Jarvis, a decorated veteran, said he would pass on the race. Others, including shadow health minister Andy Burnham, shadow home secretary Yvette Cooper, shadow education secretary Tristam Hunt are likely to join Kendall and Umunna in the race. Former foreign secretary David Miliband, whose brother narrowly defeated him for the Labour leadership in 2010, is set to make remarks Monday about his future in New York, where he serves as the president of the International Rescue Committee. Should he decide to return to London to vie for the Labour leadership, it could upend the race — many Britons believe Labour chose the wrong Miliband brother five years ago.

* * * * *

RELATED: The race to succeed Ed Miliband begins tonight

* * * * *

Unsurprisingly, the loudest critics have been the architects of the ‘New Labour’ movement that propelled former prime minister Tony Blair to power in 1997, including Blair himself. They’re right to note that Blair is still the only Labour leader to win a majority since 1974, and there’s a strong argument that they are also correct that Miliband could have made a more compelling case to the British middle class, especially outside of London.

Before he got bogged down with British support for the US invasion and occupation of Iraq in 2003, Blair was widely popular throughout the United Kingdom, positioning Labour squarely in the center of British politics and consigning the Conservative Party to hopeless minority status for the better part of a decade.

But even if Blair and Mandelson are right that turning back the clock to the 1970s or 1992 can’t provide Labour the way forward in 2015, it’s equally true that Umunna and the other Labour leadership contenders can’t simply argue that it’s enough to turn the clock back to 1997.

What’s more, in a world where senior Labour figures grumble that figures like Burnham and Cooper are too tied to the Ed Miliband era to lead Labour credibly into the 2020 election, there are also risks for Umunna or other leadership contenders to be too closely tied to the New Labour figures of the 1990s. The last thing Labour wants to do is return to the backbiting paralysis that came from the sniping between Blair and his chancellor and eventual prime minister Gordon Brown. If there’s one thing Miliband managed successfully since 2010, it was to unite the disparate wings of a horribly divided party. It will be no use for the next leader to attempt to move Labour forward if it reopens the nasty cosmetic fights of the past. Continue reading What ‘New Labour’ can and cannot teach Labour in 2015