Though he may well survive his party’s horrendous defeat in Sunday’s European elections, Nick Clegg’s decision to cling to the leadership of the Liberal Democrat will almost certainly doom it to equally damaging losses in the May 2015 British general election. ![]()

Appearing weary in a television interview after his party lost 10 of its previous 11 seats in the European Parliament, Clegg (pictured above) defied calls yesterday from both inside and outside his party to step down as leader.

It’s axiomatic that junior coalition partners tend to suffer in elections. The Freie Demokratische Partei (FDP, Free Democratic Party), which joined German chancellor Angela Merkel in government between 2009 and 2013, lost all of its seats in the Bundestag, the lower house of the German parliament, for the first time since World War II in last September’s federal elections. It, too, suffered on Sunday, losing all but three of its previous 12 MEPs in Sunday’s election as well.

In Ireland, the center-left Labour Party, the junior partner in a government led by center-right Fine Gael, lost all three of its MEPs and won just 5.3% of the vote. Its seven-year leader, Eamon Gilmore, who has served as Ireland’s Tánaiste, its deputy prime minister, and foreign affairs minister, since 2011, resigned on Monday, taking responsibility for Labour’s horrendous showing.

Gilmore’s example makes Clegg’s position even more awkward.

Paddy Ashdown, a member of the House of Lords, and the party’s leader between 1988 and 1999, defended Clegg, as did former leader Sir Menzies Campbell. But private polls, leaked to the press, show that Clegg’s Liberal Democrats are headed for an equally jarring defeat in 12 months, and that Clegg himself could even lose his seat.

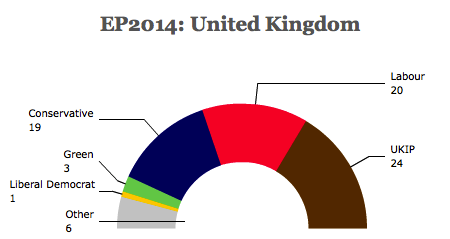

Clegg is widely viewed as having lost a series of debates with the leader of the United Kingdom Independence Party, Nigel Farage, who led UKIP to a stunning victory on Sunday, winning 27.5% of the vote and 24 seats in the European Parliament:

Farage credited his victory, in part, to the debates with Clegg, though he crowed on Monday that Clegg’s position as leader is untenable, and that he would be ‘surprised’ if Clegg leads the LibDems into the next election.

To Clegg’s credit, neither Conservative prime minister David Cameron nor Labour leader Ed Miliband were willing to debate Farage by strongly defending European integration and the continued British role in the European Union. Former Labour prime minister Tony Blair noted Clegg’s integrity yesterday for doing so, while accurately highlighting the more fundamental problem for the LibDems heading into election season:

Blair praised the way in which Nick Clegg had shown leadership in confronting the anti-EU mood in the country. “To be fair to Nick Clegg – I don’t want to damage him by saying this – over the past few years he has shown a quite a lot of leadership and courage as a leader.

“The problem for the Lib Dems is nothing to do with Europe. The problem they have is very simple: they fought the 2010 election on a platform quite significantly to the left of the Labour party and ended up in a Conservative government with a platform that is significantly to the right of Labour.

Partly in response to UKIP’s rise, David Cameron agreed last year that, if reelected, he will hold a referendum on British EU membership in 2017.

It’s natural that a party that served as a protest vehicle for decades would lose support when it finally becomes responsible for government. Clegg currently serves as deputy prime minister in a first-of-its-kind ‘Liberal Conservative’ coalition. But voters also blame the LibDems nearly as much as the Conservatives for the harsh budget cuts that Tory chancellor George Osborne has introduced over the past four years. Clegg’s personal unpopularity could worsen what already seems like a doomed campaign. Clegg’s critics within the party would prefer Vincent Cable, currently the business minister in the government, lead the LibDems instead. Cable is generally more confrontational with Tory officials, and he’s been much more skeptical in public about Osborne’s budget-cutting austerity. It’s clear that Cable would be able to draw a sharper distinction with the Tories in 2015, and he’s much more in line with what used to be the LibDem base. So far, however, Cable, like Ashdown, Campbell and other party leaders, has steadfastly backed Clegg. At age 71, Cable may not be incredibly enthusiastic about leading the LibDems through such a punishing campaign.

In the 2010 general election, Clegg was poised to lead the party to its best-ever result, after his performance in the first-ever televised debate among the major prime ministerial candidates. Amid what the press called ‘Cleggmania,’ the LibDems shot to the top of the polls. By election day, however, the LibDems won 23% of the vote, but just 62 seats, actually a net loss of five. It was nonetheless enough to deny Cameron and the Tories an outright majority, giving the LibDems their first-ever taste of government under Clegg, who has pulled the LibDems away from its traditionally leftist comfort zone and into the more market-friendly center. But the LibDems almost certainly benefitted in 2010 as the only major party to oppose British intervention in the US-led invasion of Iraq, serving as a protest vehicle for voters who had soured on 13 years of Labour rule and prime minister Gordon Brown, but who weren’t sure about voting Conservative.

The LibDems have taken their share of negative hits since May 2010.

In the 2007 leadership race, Clegg narrowly defeated Chris Huhne, who subsequently became minister for energy and climate change until his resignation in February 2012, in relation to a bizarre case in which it emerged that Huhne had tried to convince his wife take the blame for a 2003 speeding incident. Huhne eventually pled guilty to perverting the course of justice, and resigned as an MP last year.

Though Cameron, as part of the coalition agreement, agreed to hold a referendum in May 2011 on introducing a new electoral system, long favored by the Liberal Democrats, whereby an ‘alternative vote’ system would replace the first-past-the-post system, the LibDems resoundingly lost by the lopsided margin of 67.9% to 32.1%.