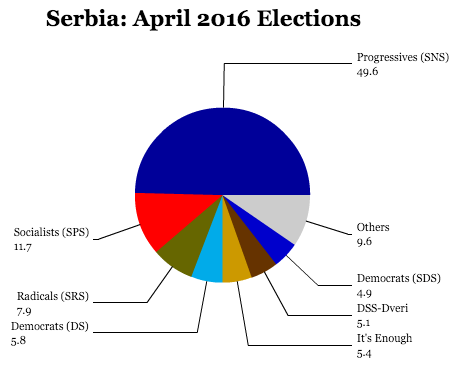

This weekend, Serbia’s prime minister Aleksandar Vučić finalized a four-year consolidation of power in early parliamentary elections that delivered a landslide victory for his center-right Serbian Progressive Party (SNS, Српска напредна странка), giving him the mandate and the support to advance political and economic reforms that he hopes could one day result in Serbia’s accession as a member-state of the European Union.![]()

In results late Sunday night, the SNS a wide lead over its nearest competitor, the center-left Socialist Party of Serbia (SPS, Социјалистичка партија Србије), which currently serves as the government’s junior coalition partner. The Socialist leader, Ivica Dačić, a former prime minister, currently serves as Vučić’s foreign minister. Several parties of the fragmented center-left and hard-right ultra-nationalist parties trail far behind in single digits. With just under 50% of the total vote on Sunday, the SNS can expect to have an absolute majority in Serbia’s unicameral, 250-seat National Assembly (Народна скупштина).

Vučic called the snap elections earlier this year, fully knowing how well his party was doing in the polls. Like it or not, Vučic and the former SNS leader Tomislav Nikolić, currently in his first term as president, will be directing Serbian policy through the end of the decade.

* * * * *

RELATED: Vučić set to consolidate political power in Serbia

with 3rd consecutive win

* * * * *

But Serbia is far from the only country in the Balkans that will vote this year, and Sunday’s vote kicks off what could become a season of electoral change across the region.

Unlike Serbia, where voters were happy to deliver Vučic the broad mandate he wanted, voters in the rest of the western Balkans are far less sanguine about their elected officials. Opposition politicians in Montenegro nearly ousted their long-serving prime minister earlier this year, though fresh elections are due before October. The twists and turns of a wiretapping scandal in Macedonia have reached fever pitch this week, with protesters marching against the government in Skopje, and a June 5 parliamentary election date is currently in doubt.

A region that still dreams of EU accession

The western Balkans are the last major region of Europe that has not yet been integrated into the European Union. With the possible exception of Turkey, it’s the final frontier of EU accession. Among the six (or seven, if you count Kosovo) countries that emerged out of the former Yugoslavia, only two of them have won EU member-state status, Slovenia and Croatia. They join only Albania in representing the western Balkans in the North Atlantic Treaty Organization.

The remaining Balkan states are in varying stages of their quests for accession:

- Macedonia was granted candidate status back in 2005, but democratic and economic backsliding have stalled its membership push, not to mention its long-running spat with Greece over the name, ‘Macedonia,’ which Greeks consider to be an inaccurate appropriation of Greek culture and history.

- Montenegro gained candidate status in December 2010, and negotiations are ongoing, though Montenegro has fully implemented just two of 33 chapters of the acquis communautaire, the body of EU law required for all member-states.

- The European Union granted Serbia candidate status in March 2012, negotiations kicked off in 2014 and Vučic is eager to conclude accession by the year 2020, though that remains incredibly optimistic.

- Albania won candidate status in June 2014, and though its negotiations have yet to begin, prime minister Edi Rama, a former artist who charged to power in 2013, is an energetic center-left figure who’s worked closely with former British prime minister Tony Blair to develop a package of EU-friendly economic and political reforms.

- Bosnia and Herzegovina applied for membership status in February 2016, but the European Union hasn’t yet granted it candidate status.

Given the existential threats that the European Union faces, hardly anyone outside the Balkans seems to have the stomach for what promises to be a difficult round of accession. The June 23 referendum in the United Kingdom on whether to leave the European Union remains too close to call, but its passage would be a major blow to the notion of ‘ever closer union.’ Much of southern Europe, most especially Greece, have still not recovered from the eurozone crisis that stretched the limits of EU financial, economic and monetary policy and that brought into question the future of the single currency. Meanwhile, the most acute refugee crisis in Europe since World War II has weakened the Schengen agreement by undermining the free movement of people within the European Union and the eradication of internal EU borders.

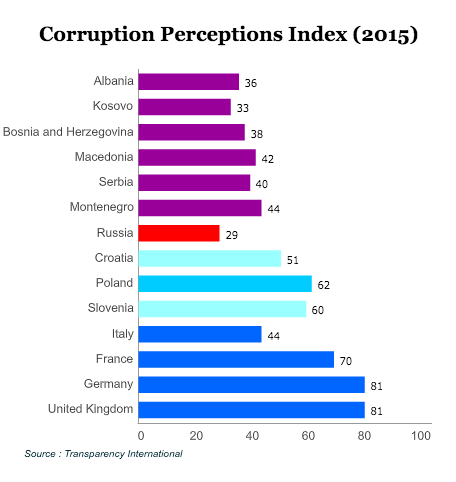

For current EU members, then, it may look like there’s precious little benefit in EU accession. But for the Balkan states, there remains enthusiasm that EU membership will force the kind of reforms that could reduce the crippling corruption that is, on general, worse in the Balkans than in the rest of Europe:

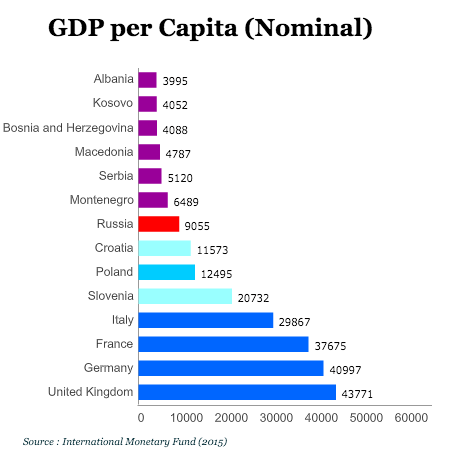

Balkans populations also hope that EU membership will also clear the path not only for reforms, but for the kind of funding that could allow them to catch up to the higher EU standard of living, which, not surprisingly lags far behind:

With eventual EU membership — and the promise it brings of greater incomes and opportunities — dangling as a carrot, it’s no surprise that Vučic has amassed so much political power in Serbia and an impressive amount of respect among European leaders. But it’s that same dynamic that could lead to massive changes throughout the rest of the region, most notably in Montenegro and Macedonia.

With eventual EU membership — and the promise it brings of greater incomes and opportunities — dangling as a carrot, it’s no surprise that Vučic has amassed so much political power in Serbia and an impressive amount of respect among European leaders. But it’s that same dynamic that could lead to massive changes throughout the rest of the region, most notably in Montenegro and Macedonia.

Wiretaps and pardons

Eleven days ago, Macedonia’s president Gjorge Ivanov pardoned 56 people, all of whom were implicated in a wide-ranging wiretapping scandal that forced the country’s powerful prime minister, Nikola Gruevski, to resign in January. Beginning in the early 2010s, Gruevski and his government were found to have wiretapped illegally up to 20,000 Macedonians, opposition figures, journalists and even diplomats. ![]()

Ivanov, who announced a decree that would end all investigations into the wiretapping scandal, set off a constitutional crisis from what had already been a crisis of governance and the rule of law, and his announcements met with sharp disapproval from EU officials and Macedonia’s political opposition.

Gruevski’s ruling VMRO-DPMNE (Внатрешна македонска револуционерна организација – Демократска партија за македонско национално единство; Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization – Democratic Party for Macedonian National Unity) has been in power since 2006. It easily won a fourth consecutive term in April 2014, though the election was hardly a fair fight.

Gruevski has spent much of the past decade stoking nationalist sentiment, which has antagonized Greece; for example, he erected an 11-foot high statue of Alexander the Great in Macedonia’s capital of Skopje. While the spat with Greece helped Gruevski, in part, to rally domestic support, it has only hardened Greek determination to block Macedonian membership not only in the European Union, but NATO as well. Meanwhile, the VMRO-DPMNE’s government has done little to introduce reforms to stem corruption or promote liberalization.

Macedonians now seem fed up with Gruevski’s empty promises and hollow rhetoric, to say nothing of the wiretapping shenanigans and his attempts to persuade Ivanov to pull the plug on the ongoing investigations.

Elections were set for June 5, but the government, fearing a rout, may try to postpone them. A meeting scheduled earlier today in Vienna among EU leaders and Macedonia’s political leaders was cancelled, even as the intensity of Macedonia’s protesters increases.

Zoran Zaev, Macedonia’s opposition leader and the head of the center-left Social Democratic Union of Macedonia (SDSM, Социјалдемократски сојуз на Македонија), was instrumental in revealing the extent of the wiretapping scandal, though only after Gruevski tried to have Zaev jailed for allegedly attempting to illegally toppling the government.

For years, Zaev has opposed Gruevski’s nationalist showmanship and denounced the government’s flashy development projects as wasteful vanity spending. Now, with Ivanov’s announcement to suspend the wiretapping scandal that Zaev himself helped to reveal, the opposition leader has joined the front lines of the protesters. There’s a sense that he could soon be leading the country, though he pledged earlier this month to boycott elections without additional reforms to guarantee political freedom and a free and fair electoral process. An original plan to hold elections in April has already been postponed once to June and could well be delayed again.

Negotiations over the conduct and timing of the Macedonian elections are just the beginning of what could become an even more tumultuous year. If Zaev and an opposition coalition forces VMRO-DPMNE from power, no one knows exactly how willingly Gruevski and his allies will concede. Moreover, from day one, a Zaev-led government would be locked in a high-stakes battle with Ivanov to reinstate the wiretapping investigation.

Đukanović’s last stand?

Though it officially won its independence from Serbia only in June 2006, Milo Đukanović has controlled Montenegro like a personal fiefdom since 1991, when he was first elected prime minister. Đukanović has held power, on and off, ever since.![]()

Polls show that Đukanović and his Democratic Party of Socialists (DPS, Demokratska Partija Socijalista Crne Gore) hold a wide lead in elections that have to be called within the next six months. But that belies the frustration that’s built for a quarter-century with Đukanović and his family, whose opponents argue that they run Montenegro as their own personal duchy of corruption.

As in Serbia, Montenegro’s opposition is even more split today than it was in the last election. The conservative opposition Democratic Front (Demokratski front) did poorly in the 2012 parliamentary elections, and its leader Miodrag Lekić narrowly lost the 2013 presidential election. Last year, however, Lekić left the party to form Democratic Alliance (DEMOS, Demokratski savez), a competing center-right party.

In December, however, Đukanović only narrowly survived a vote of no confidence in Montenegro’s unicameral, 81-member parliament (Skupština Crne Gore), following widespread protests that began in October over longstanding suspicions of Đukanović’s corruption. Protesters demanded his resignation and a transitional government; Đukanović himself spent half of the 2000s fending off a criminal inquiry into corruption from an Italian prosecutor. Đukanović’s long-time allies, the Social Democratic Party (Socijaldemokratska Partija Crne Gore), left government for the first time since 1998.

Đukanović has hoped that Montenegro’s relatively strong economy and a general trend toward liberalization will distract from his critics’ worst allegations. Moreover, Montenegrins will go to the polls as he pursues the country’s accession to NATO after formally opening talks in February. It’s a step that has appalled Moscow, which still holds plenty of economic and cultural power in the western Balkans, despite the region’s aspirations to integrate further with the rest of Europe.

Đukanović, who is only 54 years old, seems unlikely to take the opportunity of 2016 elections to step down. But it’s not inconceivable that, despite Montenegro’s more successful strides toward NATO and, eventually, EU accession, he too will face the kind of popular wrath that is now greeting Gruevski across Macedonia.