Though the full-throated nature of the endorsement of former Brazilian president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva of acting Venezuelan president Nicolás Maduro is perhaps somewhat of an eyebrow-raiser, it should not be unexpected, and it highlights the extent to which much of official Latin America has a vested interest in the continuation of chavismo — for now at least. ![]()

![]()

Lula is perhaps second to just Fidel Castro in terms of living politicians who are nearly universally popular throughout Latin America, so his hearty endorsement gives Maduro some international credibility, extolling both Chávez and Maduro for their passion for the rights of the poor, and it may well sway some voters who are on the fence between Maduro and challenger Henrique Capriles:

Lula says in a video released by VTV, astate-controlled television station, that he got to know Maduro in his years as foreign minister, and that Maduro will carry on Chávez’s grand hope of transforming Venezuela into a more just country where oil wealth is shared with those suffering most in society. While Lula (pictured at top, left, with Chávez) notes that the decision is for Venezuelans alone, and he doesn’t want to interfere, but he could not help but share his testimony about Maduro, declaring, ‘Maduro Presidente; es la Venezuela que Chávez soñó‘ (Maduro for President! It’s the Venezuela of which Chávez dreamed!

But as Reuters noted last month, there may be more to Lula’s endorsement than just ideological solidarity:

“In the near term, a Maduro win would be best,” said Jose Augusto de Castro, head of Brazil’s Foreign Trade Association….

Key infrastructure projects launched during the 14 years of Chavez’s government, from the Caracas metro expansion to bridges across the Orinoco river that divides Venezuela, are run by Brazilian firms like Odebrecht.

Lula refused throughout his tenure as president from 2003 to 2010 to criticize Chávez openly, to the consternation of U.S. foreign policymakers. But Chávez’s more strident socialist path may have made Lula’s more moderate leftism seem even tamer in contrast, and Lula’s example in Brazil stands as a pointed counter-example to chavismo in many ways — Lula managed to reduce poverty in Brazil much as Chávez did in Venezuela, but he did so while also cultivating ties to the business elite and development from the United States, the European Union and the People’s Republic of China alike.

Lula’s friendship with Chávez meant that Brazilian firms were shielded from many of the tumultuous aspects of doing business in Venezuela, most of all Chávez’s snap decisions to expropriate and nationalize industries. Furthermore, Brazil has benefitted from Venezuela’s oil wealth, and trade between the two countries quintupled over the course of Lula’s presidency, though the ties were strategical as well:

[T]he main goals of Lula and Chávez were geopolitical. Samuel Pinheiro Guimarães, the most influential diplomat in the Brazilian chancellery, explained that Brazil’s strategy sought to prevent the “removal” of Chávez through a coup, to block the reincorporation of Venezuela into the North American economy, to extend Mercosur with the inclusion of Bolivia and Ecuador and to hinder the US project to consolidate the Pacific Alliance, which includes Chile, Colombia, Mexico and Peru.

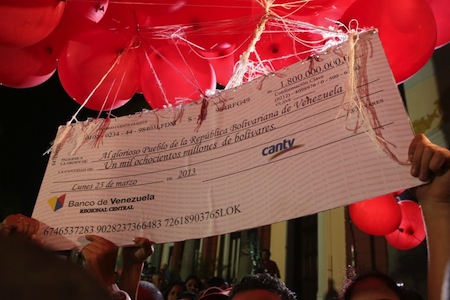

If you didn’t need a reminder, Latin American leaders and politicians from the moderate left, populist left and the right all attended Chávez’s funeral in March — showcasing just how entrenched chavismo has become in the region, if for no other reason than as a channel for oil subsidies and alternative finance.

Indeed, with the suspension of Paraguay from Mercosur (Mercado Común del Sur) following the impeachment and removal of Fernando Lugo in June 2012, Brazil and other countries wasted little time in making Venezuela a full member — Paraguay’s senate had long blocked Venezuela’s membership.

Campaigning kicked off today officially for the April 14 presidential race. I attempted yesterday to argue a rationale for supporting each candidate — the policy case for Maduro is here, and the policy case for his challenger, Capriles, is here.