<See below Suffragio’s preview of Iran’s June 2013 presidential election, followed by a real-time listing of all coverage of Iranian politics.>

Citizens in the Islamic Republic of Iran will select a new president on June 14 from among eight pre-vetted candidates.

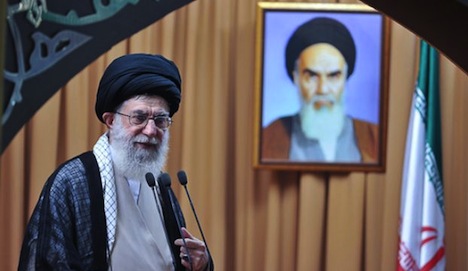

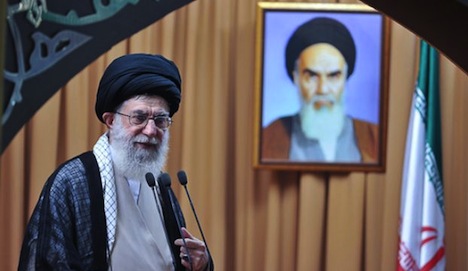

Under Iran’s unique system, the ultimate authority is the Supreme Leader, who controls the military as well as virtually all other branches of government, including the executive. Upon the founding of the Islamic Republic in 1979, grand ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini returned from exile in Iraq and France to become its first Supreme Leader. Upon his death in 1989, ayatollah Ali Khamenei (pictured above, with Kohmeini in background) was appointed Supreme Leader and has held the office in the ensuing 24 years.

The Supreme Leader is appointed by the Assembly of Experts, an 86-member body of Islamic scholars elected to eight-year terms. The Assembly of Experts also has the power to oversee and even dismiss the Supreme Leader although, in practice, its members are essentially subservient. Its current chair, since 2011, is Mohammad Kani, a conservative loyal to Khamenei.

The Iranian president, elected directly for a four-year term, with a limit of two consecutive terms, remains subservient to the Supreme Leader. Although Iran’s president can set both foreign and domestic policy, in practice, the president can do very little without the consent of the Supreme Leader. Since 1981, Iran has had four presidents, and each of them has served two full terms:

- Ali Khamenei, 1981 — 1989. Khamenei, before his elevation to Supreme Leader, served as Iran’s president in the 1980s when the country was focused on a difficult war against Iraq after Saddam Hussein invaded Iran in September 1980 after the Islamic Revolution, in large part due to fears that Iran’s Shi’a majority would embolden the Shi’a minority in his own country. Although Iran regained its territory by 1982, the war lasted for another six years and featured the use of chemical weapons by Iraqi forces against Iranians, and anywhere from 300,000 to 900,000 Iranians were killed.

- Hashemi Rafsanjani, 1989 — 1997. Rafsanjani’s presidency focused on rebuilding Iran after its costly war with Iran and transitioning its role in the Middle East following the breakup of the Soviet Union and the increased building of U.S. forces in the Middle East following the Cold War, notably during the 1990-91 war against Iraq to liberate Kuwait.

- Mohammed Khatami, 1997 — 2005. Khatami emerged as a dark-horse candidate to win the 1997 presidential election and remains Iran’s most prominent reformist voice. Under his leadership, he achieved limited gains in relaxing freedoms within Iran, and he continued Rafsanjani’s approach toward conciliation with the United States and Europe, especially with respect to Iran’s nuclear energy program, which emerged as a hot-button issue in the early 2000s in light of U.S. and Israeli fears that a nuclear-powered Iran could easily pursue a nuclear weapons program.

- Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, 2005 — 2013. Ahmadinejad (pictured below) won the presidency in 2005 over Rafsanjani as a conservative populist who focused on Iran’s economic woes. The former mayor of Tehran, Ahmadinejad came to office as a voice of the poorer working class, unlike his predecessors. Unlike Khatami and Rafsanjani, Ahmadinejad’s administration has taken a harder line with respect to the West, especially in defense of Iran’s sovereign right to develop nuclear energy. That’s left Iran subject to U.N. sanctions and other measures that have largely left it isolated diplomatically and struggling economically at the end of Ahmadinejad’s second term.

Iran’s unicameral legislature is called the Islamic Consultative Assembly (Majles), and it’s comprised of 290 directly elected members. It’s not nearly as powerful as the Supreme Leader, the president or even the Guardian Council, but it has significant powers with respect to Iran’s public budget. In the most recent parliamentary elections, conservatives won around 180 seats, of which around 100 were ‘principlists’ loyal to Khamenei and only around 40 of which were conservative loyalists of Ahmadinejad, with around 70 seats going to reformists and moderates of various stripes and around 20 seats going to religious minorities, including Armenian Christians and Jews. Its speaker, since 2008, has been Ali Larijani.

The more powerful Guardian Council is a body of 12 members, six of which are appointed by the Majles and six of which are appointed by the Supreme Leader, which has the power to interpret laws passed by the Majles and other constitutional issues. Its chief role, however, is vetting and approving candidates who run for public office — including candidates for president.

The current presidential election takes place under the backdrop of the fraught 2009 election, in which Ahmadinejad officially defeated former prime minister Mir-Hossein Mousavi by 66.6% to 33.9%, though Mousavi’s supporters launched the ‘Green movement’ protests in response, alleging voter fraud. Although the evidence of actual fraud was not incredibly strong, the Supreme Leader and his supporters responded with vigor to put down the protests, placing Mousavi and key reformist allies under house arrest (they remain so even today) and placing many activists in detention.

Former president Rafsanjani, who registered to run for president in 2013, and was rejected as a candidate by the Guardian Council in May 2013, had hewn a middle road between Khamenei and the protestors throughout the 2009 post-election crisis, supporting the Supreme Leader but also subtly criticizing the heavy-handed response.

The election will come down to eight candidates and, if no single candidate wins a majority of the vote, the two top contenders will face off in a June 21 runoff.

Those candidates are, as announced by the Guardian Council:

- Mohammad Reza Aref, the reformist candidate, who served as Khatami’s communications minister and vice president.

- Hassan Rowhani, a moderate candidate with ties to Rafsanjani, a former head of Iran’s Supreme National Security Council and its chief nuclear negotiator from 2003 to 2005.

- Mohammad Baqer Qalibaf, a ‘principlist’ conservative, who succeeded Ahmadinejad as Tehran’s mayor in 2005 and has been a relatively aggressive Ahmadinejad critic.

- Gholam Ali Haddad-Adel, a principlist and the former speaker of the Majles in the mid-2000s, whose daughter is married to the Supreme Leader’s son.

- Ali Akbar Velayati, a principlist and currently a top advisor to the Supreme Leader on international affairs and Iran’s foreign minister from 1981 to 1997.

- Saeed Jalili, a principlist, and the current head of the Supreme National Security Council and Iran’s current nuclear negotiator, who has strong connections to conservatives tied to both Khamenei and to Ahmadinejad.

- Mohsen Rezai, a conservative who formerly headed the Revolutionary Guards and who unsuccessfully ran in 2005 and 2009 as well.

- Mohammad Gharazi, a former oil minister and communications minister in the 1980s and the 1990s.

See below all of Suffragio‘s coverage of politics in Iran:

Ten reasons why the Iran sanctions Senate bill is policy malpractice

January 16, 2014

Obama-Rowhani call a historic first step in securing better US-Iranian relations

September 27, 2013

The big news on Syria this weekend? Iran’s surprisingly mellow reaction to US military plans

September 1, 2013

As Rowhani takes power, U.S. must now move forward to improve U.S.-Iran relations

August 6, 2013

Did Rowhani’s support in Iran outperform the potential of a Rafsanjani candidacy?

June 17, 2013

Moderate cleric Rowhani wins stunning first-round victory in Iran presidential election

June 15, 2013

What U.S. commentators get wrong about Iran and why Iran’s election matters

June 14, 2013

Voting wrapping up in Iran’s presidential election

June 14, 2013

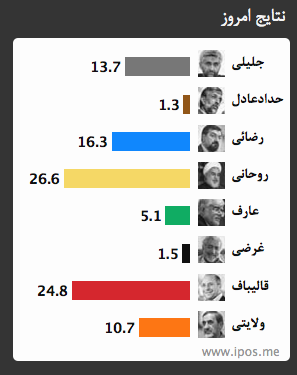

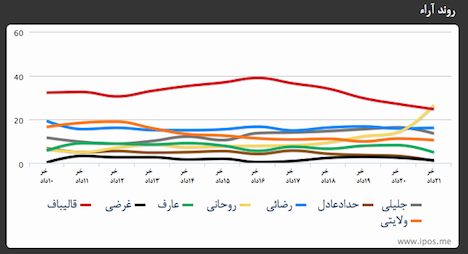

Rowhani, Qalibaf appear to lead polls to top Friday’s vote, advance to June 21 runoff

June 12, 2013

The incredibly shrinking president: Ahmadinejad’s subdued role in Iran’s presidential race

June 12, 2013

And then there were six: the dwindling Iranian presidential field

June 11, 2013

How the West could learn to stop worrying and love a nuclear Iran

June 10, 2013

What will Mohammed Khatami do?

May 30, 2013

In one year, South Asia and the Af-Pak theater as we know it will be transformed

May 28, 2013

Why Iran is not a totalitarian state

May 23, 2013

A look at the eight presidential candidates approved by Iran’s Guardian Council

May 21, 2013

Rafsanjani, Mashaei both disqualified from running for Iranian presidency

May 21, 2013

Iran awaits Guardian Council decision on Rafsanjani, other presidential contenders

May 20, 2013

Official Iranian parliament results

March 5, 2012

Iran parliamentary election: in the shadow of 2009 and 2013

March 2, 2012

![]()