On July 9, voters in the world’s fourth-most populous country, the world’s third largest democracy and the world’s largest Muslim country will directly elect its president for just the third time in its history.

From independence to Sukarno to Suharto to SBY

Indonesia’s initial post-independence period was dominated by two authoritarian leaders, the first of whom was the Soviet-backed Sukarno, who led Indonesia from the end of the Dutch colonial era and World War II in 1945 (and formal Dutch recognition of Indonesian sovereignty in 1949) until 1967.

The left-leaning Sukarno developed the principles that would cumulatively be come to known as pancasila, the dominant state ideology for the next four decades, which even today influences the nature of Indonesian governance and politics. Pancasila is comprised of five principles — in brief: belief in God, just and civilized humanity, Indonesian unity, ‘guided democracy,’ and social justice.

Under Sukarno, those principles sometimes took a hard edge — ‘guided democracy’ hardly meant any kind of cognizable participatory voting at all, while ‘Indonesian unity’ served to motivate a brutal and relentless campaign in West Papua in the early 1960s, a process that ended in 1969 with the incorporation of Irian Jaya province.

Following a military coup in 1965 that severely limited Sukarno’s power, which saw an unprecedented amount of political and social upheaval amid a state transforming into a staunchly anti-communist country (the famous ‘year of living dangerously’). Military general Suharto became Indonesia’s president in 1967, finalizing the country’s turn to his ‘New Order,’ a new Western-oriented regime.

Suharto ruled with even tighter control, and Indonesia doubled down on its West Papua approach with a three-decade campaign to subdue the formerly Portuguese colony of East Timor, beginning in 1975. At the same time, Suharto furthered the attempts to bring more unity to an archipelago of thousands of islands dominated by the most populous island, Java, which today contains 56% of Indonesia’s 247 million citizens.

Despite a diverse array of languages, cultures, traditions and ethnicities, Java had long been the center of the Dutch East Indies in the colonial period as well as the Majapahit empire that extended control over much of the empire between 1293 and 1500.

Though the concept of a pan-Indonesian language began with efforts in 1928, well before independence, the invented language of Bahasa Indonesian, which draws heavily on Malay, became an official language after 1945. Today, Bahasa Indonesian is the lingua franca of the entire country, one of its most unifying elements.

After three decades in power Suharto’s end came to an end in May 1998. In a post-Cold War era, without US economic and military support, Suharto’s elites found themselves unable to withstand the Asian financial crisis, which began with a Thai currency crisis in April 1997 and that extended from South Korea to Indonesia. The fall in the Indonesian rupiah‘s value and the resulting economic recession proved too much for Suharto’s regime, all while facing down growing criticism from pro-democracy activists in Jakarta to pro-independence guerrillas in East Timor.

Out of the ashes of Suharto’s ouster came a period of reformasi, during which the framework of Indonesia’s current democracy came into relief. Indonesian officials, under caretaker president B. J. Habibie, significantly amended Indonesia’s 1945 constitution to introduce new measures for greater democracy, additional freedoms and check and balances on presidential power.

Indonesia’s legislature elected its first post-Suharto president, Islamist leader Abdurrahman Wahid (known as ‘Gus Dur’) in 1999, who was succeeded after his impeachment in 2001 by the more secular Megawati Sukarnoputri — the daughter of Indonesia’s first president.

Megawati, however, lost her bid for the presidency in the country’s first direct elections in 2004. Instead, she lost to her former minister of security, Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono (known as ‘SBY’), who has governed Indonesia for the past decade, decisively defeating Megawati in a landslide in their 2009 rematch.

Though Yudhoyono (pictured above, right, with Australian prime minister Tony Abbott) has been criticized for doing too little in his decade in power, he’ll transfer to the next president an investment-grade Indonesia with robust democratic and legal institutions. That doesn’t mean there’s not room for reforming Indonesia’s still-too-inefficient economy nor does it mean that Indonesia is corruption-free.

But Yudhoyono has a handful of praiseworthy achievements:

- he largely accepted that Indonesia’s military forces were to blame for human rights atrocities in the Suharto era;

- SBY continued to recognize the newly independent Timor-Leste;

- he adroitly handled the aftermath and international efforts at recovery from the December 2004 tsunami that killed over 200,000 Indonesians;

- SBY signed a peace deal with pro-independence rebels in the western Aceh province in 2005;

- he kept fundamentalist Islamic terrorist attacks at bay without resorting to Suharto-style authoritarian means (if not eliminating them completely); and

- he largerly presided over an era of strong economic growth. Indonesia’s GDP skyrocketed during the SBY years from $256.8 billion in 2004 to $878 billion in 2012. Between 2004 and 2012, Indonesia notched an average GDP growth rate of 5.78%. Impressive, if not quite the same economic magic that China and other economies have harnessed over the last decade.

The race to succeed Yudhoyono pits two very different candidates against one another in what’s become the closest race since the transition to direct presidential elections began.

Joko Widodo — the young reformer

Jakarta governor Joko Widodo (known as ‘Jokowi’), age 53, served as mayor of Sukarna (or Solo) between 2005 and 2012. Elected in an upset victory in Jakarta’s gubernatorial election in September 2012, Jokowi became the rising rock-star of Indonesian politics, winning comparisons to US president Barack Obama — a popular figure in Java, in part because he spent four years of his adolescence in Jakarta.

A man of humble means, unique in Indonesian politics, Jokowi is known for a hands-on administrative style in the tradition of blusukan, impromptu visits throughout Solo and Jakarta to check in with everyday constituents and to check in on the performance of his governments. In less than two years as Jakarta governor, he introduced additional spending for education, raised the minimum wage and rolled out a universal halt care program almost immediately after his election.

That common touch, along with a corruption-free record, earned him a reputation as a reformist who could deepen Indonesia’s path to a modern economy and a developed democracy. But with no experience at the national level, and with no real way to deploy the principles of blusukan across thousands of islands, Jokowi’s rivals have attacked him boldly for being too inexperienced and for advancing only the vaguest of campaign policy platforms.

Whispering campaigns suggest that Jokowi is a Christian (a slur for a country that’s 87% Muslim) and that he’s Chinese (he’s actually Javanese, but anti-Chinese sentiment was a common instrument of displacement during the Suharto era). When the official campaign ended on July 5, Jokowi left the country for two days in the middle of the Muslim month of Ramadan to make the hajj pilgrimage to Saudi Arabia, emphasizing his Muslim credentials.

He represents the Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P, Partai Demokrasi Indonesia Perjuangan), the party of Indonesia’s first president and of former president Megawati. Today a slightly center-left party, it’s been in opposition under Megawati for a decade, and there’s a general impression that Megawati (and not Jokowi) holds the true behind-the-scenes power within the PDI-P and, accordingly, would hold considerable influence in a Jokowi administration.

His running mate, Jusuf Kalla, served as vice president to Yudhoyono between 2004 and 2009, before pursuing his own presidential bid five years ago. A native of south Sulawesi (Sulawesi, with 18.5 million residents, is Indonesia’s third-most populous island after Java and Sumatra), Kalla also served at the time as the leader of Golkar (Partai Golongan Karya, Party of the Functional Groups), the dominant party of the Suharto era and today a mildly center-right party. At times during Yudhoyono’s first term, Golkar’s dominance in the Indonesian legislature made Kalla a more influential force on domestic policy than anyone else in the country, Yudhoyono included. But he brings to the ticket experience that Jokowi lacks — at least at the national political level.

Though Golkar’s current leadership isn’t supporting Jokowi, a handful of other parties have lined up behind him, including:

- Partai Kebangkitan Bangsa (PKB, National Awakening Party), one of Indonesia’s most longstanding Islamist political parties, is closely connected with Nahdlatul Ulama (NU), a Sunni Islam group founded in 1926 that operated int he Sukarno era as the only legal Islamist party.

- Nasdem (Partai Nasdem), a small, secular party.

- Hanura (Partai Hati Nurani Rakyat, The People’s Conscience Party), a 2008 spinoff of Golkar founded by Golkar’s 2004 presidential candidate and controversial former military leader, Wiranto.

Prabowo Subianto — the strongman

His opponent is Prabowo Subianto, a former military commander who left Golkar in 2008 to form Gerindra (Partai Gerakan Indonesia Raya, the Great Indonesia Movement Party) when it became clear that Golkar’s leaders had no intentions of nominating him for the presidency in 2009. Instead, he wound up running as Megawati’s vice presidential candidate on a ticket with the PDI-P.

This time around, Prabowo gained traction slowly over the past year with a populist message of economic nationalism, the kind that led Indonesian lawmakers to pass a recent law limiting the export of raw mineral ore. That’s led investors to regard Prabowo warily, with expectations that, far from liberalizing the Indonesian economy, he might introduce new taxes or foreign restrictions, all while creating new debt-financed projects in the state capitalist tradition.

But if it’s economic nationalism that led Gerinda to a third-place finish in the April legislative elections, it’s outright political nationalism that’s brought Prabowo into an essentially tied race in July. After trailing Jokowi by between 20 and 30 percentage points as recently as two months ago, Prabowo has effectively narrowed the gap. He’s done so with a generally sharper campaign, shrewder alliances and with much of Indonesia’s television media supporting a Prabowo candidacy.

Opening his campaign in a military-style rally on horseback, he’s billed himself as a candidate who will be a ‘strong’ president capable of ‘firm’ leadership. He’s called into question the need for Western-style democracy during the election, and critics worry that he will drag Indonesia further away from political reform and closer to the ‘New Order’ era of Suharto. Prabowo, after all, was once Suharto’s son-in-law, and though he divorced in 2001, he’s close to his ex-wife, Siti Hediati Hariyadi (known as ‘Titiek’).

As a top military general in the Suharto era and the leader of Indonesia’s special forces, Prabowo headed the 1978 campaign that killed Timorese national hero, Nicolau dos Reis Lobato. He’s also been accused of responsibility a 1983 massacre in the East Timorese village of Kraras, and he lost his military command in 1998 when he was implicated in the kidnapping and torture of 23 pro-democracy activists, charges that Prabowo denies.

After a stint in Jordan, Prabowo turned to business. Descended from Javan royalty, his brother is one of the wealthiest members of the global Indonesian elite. But he soon turned to politics, and he’s now on the threshold of winning the most important office in Indonesia.

His running mate, Hatta Rajasa, is the leader of the Partai Amanat Nasional (PAN, National Mandate Party), one of Indonesia’s mildly Islamist parties. But Hatta is also one of the most high-profile economic policymakers of the Yudhoyono administration. Hatta served as transportation minister from 2004 to 2007, was promoted to state secretary from 2007 to 2009 and, until his vice presidential nomination in May, served as Indonesia’s coordinating minister for economics in Yudhoyono’s second term.

In addition to Gerindra (which is currently in opposition), Prabowo enjoys the support of nearly all of the current governing parties:

- Golkar, under the leadership of Aburizal Bakrie, has endorsed Prabowo, though it’s not certain if all of Golkar’s voters will follow that lead, considering that Kalla is running as Jokowi’s running mate.

- In addition to Hatta’s PAN, Prabowo has won the support of two more of the four main Islamist parties, the Partai Keadilan Sejahtera (PKS, Prosperous Justice Party) and the Partai Persatuan Pembangunan (PPP, United Development Party).

- In the last week of the campaign, Yudhoyono’s own party, the Partai Demokrat (Democratic Party) endorsed Prabowo too.

State of the race

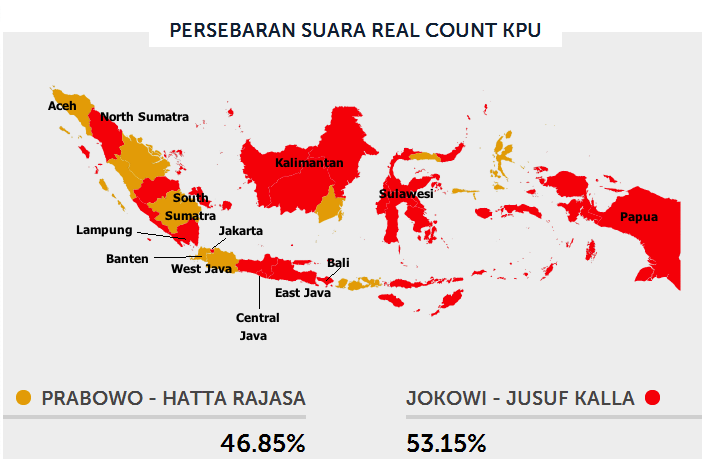

The final Australia-based Roy Morgan poll, conducted in late June, found Jokowi with 52% support and Prabowo with 48% support, a too-close-to-call lead for the young Jakarta governor.

Jokowi had a slightly higher lead in the most populous island of Java, by a margin of 53.5% to 47.5%, while Prabowo had a wider margin on Sumatra, the second-most populous island, by a margin of 60% to 40%. Jokowi led on the remaining islands, in Sulawesi by a margin of 60.5% to 39.5%.

Female voters preferred Jokowi by a margin of 55% to 45%, while male voters preferred Prabowo by a 51% to 49% margin.

Younger voters slightly favored the elder candidate, Prabowo, by a slight margin, while older groups increasingly supported Jokowi.

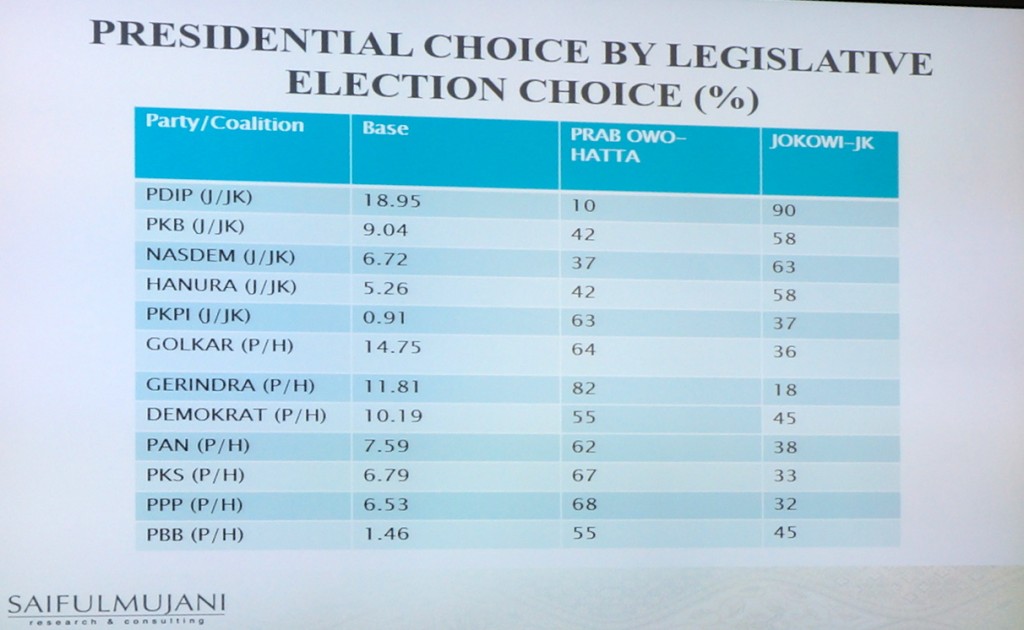

What the April legislative elections tell us

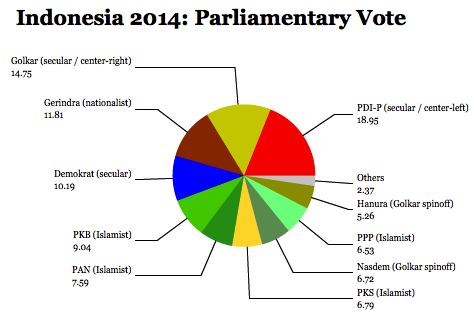

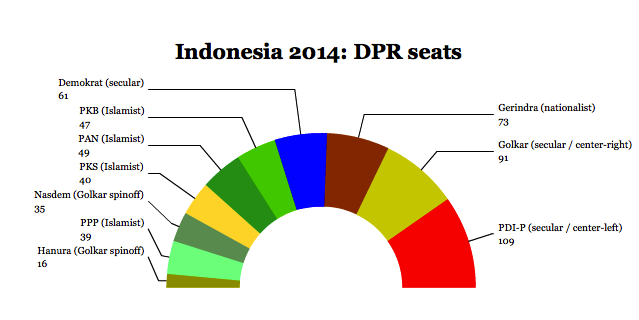

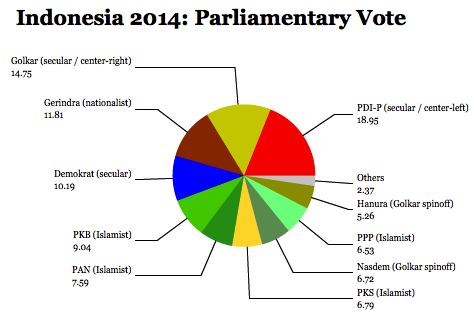

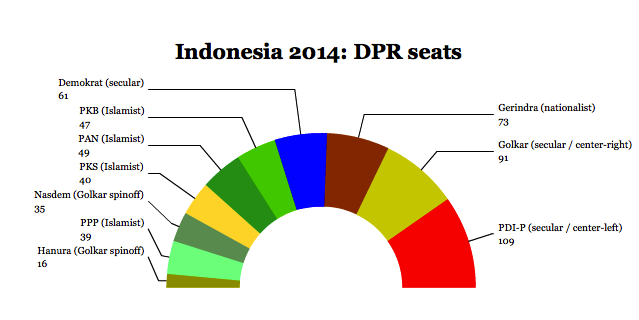

In April, Indonesians voted for all 560 members of the Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat (DPR, People’s Representative Council) and the additional 132 members of the non-partisan Dewan Perwakilan Daerah (DPD, the Regional Representative Council), a second legislative body formed in 2004 with relatively more limited powers than the DPR. Both bodies have fixed five-year terms.

Under Indonesia’s somewhat arcane process, a party (or a coalition of parties) must win either 25% of the national vote in the April parliamentary elections or hold 20% of the seats in the Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat (DPR, People’s Representative Council) in order to nominate a presidential candidate. That forced, throughout May and early June, intense behind-the-scenes discussions to form coalitions and nominate vice-presidential running mates.

It’s a somewhat peculiar system, and it’s one that will change with the 2019 election, when Indonesians will vote simultaneously for a legislature and a president. It’s a system that, ironically, would have almost certainly resulted in a Jokowi win, had both elections been held in April. Instead, Jokowi finds himself in a tight race against Prabowo.

There were signs, however, that Jokowi’s strength was less than might have been expected.

In the April elections, though the PDI-P indeed won the largest share of the votes, it was far less than the party expected, having timed their announcement of Jokowi as its presidential candidate just days before the voting. As it turns out, the PDI-P only narrowly edged out Golkar. Moreover, Indonesia’s four Islamist parties together won nearly 30% of the vote, demonstrating their continued viability among conservative Muslim voters.

Gerindra, though it placed third, marked its best-ever performance, while the fourth-place finish of SBY’s Democrats foreshadowed the relatively minor role they would play in vice-presidential and coalition talks.

All told, it means that Jokowi will be hard-pressed to push through an agenda as president without winning over support from other parties.

* * * * *

Here’s the full list of Suffragio‘s 2014 coverage of the Indonesian presidential and legislative elections:

Indonesia post-mortem: why young cosmopolitan voters chose Prabowo

July 28, 2014

It’s official: Jokowi was Indonesian presidential election

July 22, 2014

What Jokowi’s apparent victory in Indonesia means

July 9, 2014

Jokowi declares victory on basis of ‘quick count’ Indonesia election results

July 9, 2014

What Indonesia’s election means for Timor-Leste

July 7, 2014

Indonesia’s Prabowo all but declares he’ll become Suharto 2.0 if elected

July 1, 2014

Ruling Democrats in Indonesia endorse Prabowo

June 30, 2014

Will Prabowo Subianto become Indonesia’s next president?

June 28, 2014

In Indonesia, it’s Jokowi-Kalla against Prabowo-Hatta

May 20, 2014

Veepstakes, Indonesia style — will Kalla return as vice president?

May 12, 2014

Jokowi effect falls flat for PDI-P in Indonesia election results

April 9, 2014

Four key points to watch as Indonesia elects a new parliament

April 5, 2014

Who is Joko Widodo?

April 3, 2014

Top photo credits to Bernard Anthony Burrola — Indonesian capital by Jakarta by night and Prambanan, the iconic 9th century Hindu temple in central Java.

![]()

![]()