It’s official — the International Olympic Committee has awarded the 2022 Olympic Winter Games to Beijing.

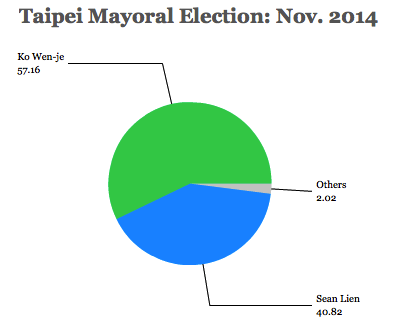

Ultimately, China’s successful bid faced little competition after Oslo and several other finalist cities withdrew from consideration after cost considerations and other hassles. Beijing, which was bidding to become the first city to host both the Summer and Winter Games, already hosted the 2008 Summer Games as a way to prove its mettle as a host city, and it has already built much of the Olympic infrastructure it would need to host again — sparing its sole competitor, Almaty, from the task of building stadiums that, as in most Olympic host cities, lay fallow for decades thereafter. Kazakhstan has relatively little experience at throwing international events, and it certainly doesn’t have the budget that China (or Russia’s 2014 Sochi Winter Games) could have promised.

Nevertheless, Kazakhstan would have been the first central Asian country ever to host either the winter or the summer games, and by 2022, it will gather experience through hosting the 2011 Asian Winter Games and the 2017 Winter Universiade. It also had the benefit of offering real snow, unlike Beijing, a fact that its proponents reiterated throughout the competition.

While Almaty’s selection might have raised more uncertainty than Beijing’s, it would have more greatly fulfilled the Olympic Charter’s stated purpose:

The goal of the Olympic Movement is to contribute to building a peaceful and better world by educating youth people through sport practised in accordance with Olympism and its values.

Central Asia has long been overshadowed by its neighbors Russia (which controlled the region when all five of its countries were swept into Soviet Union) and China (which is home to the region’s largest and most dynamic city, Urümqi). But its location has made it incredibly important to global trade and geopolitics — and, in the 21st century, to Russia, to China or to the United States, a leverage that Kazakhstan and its neighbors have used to great effect, and it that’s what Kazakh diplomats mean when they speak about their country’s ‘multi-vector’ foreign policy.

It’s hard to think of a region of the world so little understood and even more rarely considered than central Asia, and Almaty’s selection as the site of the 2022 Winter Games would have drawn a rare and welcome spotlight on Kazakhstan, specifically, and central Asia generally — warts and all.

* * * * *

RELATED: As Putin blusters over Kazakhstan,

what follows Nazarbayev?

* * * * *

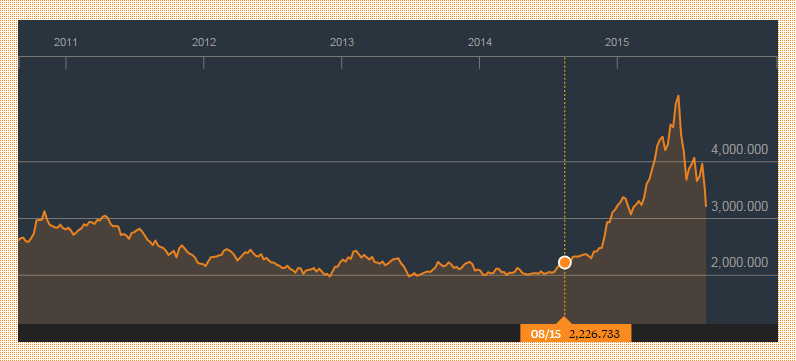

And there are a great many warts. Kazakhstan has been ruled by the same man, the 75-year-old Nursultan Nazarbayev, since 1989 when the country was still a republic in the Soviet Union. Despite duly conducted show ‘elections,’ it’s not a democracy and, also like China, it’s received harsh international condemnation for human rights abuses. Under Nazarbayev, Kazakh nationalism (vis-à-vis Russian nationalism) has been a greater priority than ethnic or sexual minority rights. Its sudden oil wealth, developed over the past two decades, has boosted the odd architecture of Astana, the country’s new capital, and widening corruption (it ranked 126 in the latest Transparency International rankings of corruption perceptions — worse than China’s ranking of 100 but better than Russia and the other four ‘stans’ of central Asia). Its dependence on petrodollars, as oil prices remain subdued, demonstrates just how much the economy should diversify. Its record on press freedom is very poor, but not quite as poor as Beijing’s. On balance, Kazakhstan is no worse than China when it comes to human rights and democracy and, on many vectors, it’s a less repressive country than China.

Of course, Kazakhstan (a country of 17 million people) doesn’t boast one of the world’s largest economies. Yet, at between $212 billion and $231 billion, it’s more than three times larger than the closest central Asian alternative, Turkmenistan. For all of Nazarbayev’s failings, he personifies Kazakh pride at clawing back their own nation-state after centuries of Russian colonization and economic subjugation that began in the early 1700s. Nazarbayev has used his petro-fueled bully pulpit to call for more ambition among the Muslim world, scolding the World Islamic Forum in 2011 for dragging its feet on modernizing. He’s a hero among the nuclear non-proliferation set because of his decision to give up Kazakhstan’s nuclear weapons — a policy that Nazarbayev has skillfully used to generate goodwill on the global stage and in the international media.

Perhaps most importantly, with Russian designs on its near-abroad ever more menacing in president Vladimir Putin’s third term, from Ukraine to Georgia, central Asia has also felt some uneasy pressure from Moscow. Leading Russian politicians hungrily eye Kazakhstan, especially the northern plains where many ethnic Russians currently reside (ethnic Russians comprise nearly 24% of the population). There’s a real question as to whether Kazakhstan will remain a stable, independent country in the coming post-Nazarbayev era — Putin could easily take advantage of turmoil if the political transition to the next generation of leaders isn’t smooth.

Almaty, still the country’s mountain-dazzled cultural and financial center (but no longer the capital since 1997), lies in the far southeastern corner of the country, closer to China and Kyrgyzstan (and even Tajikistan and Uzbekistan) than Russia. That’s one reason why the country, just six years after independence, moved its capital to the northern steppe, transforming sleepy Akmola into a city of over 850,000 today — that’s certainly some feat for a country aiming to erect Olympic infrastructure in the next seven years.

Moreover, choosing Beijing doesn’t rid the Olympic committee of its woes with respect to human rights and autocracy — China’s record is arguably worse than Kazakhstan’s on both counts. Given that there are around 50 Chinese cities with populations at least as large as Chicago, it’s somewhat disappointing that Beijing wants two bites at the same Olympic apple. China is far more diverse and culturally engaging that its urban eastern coastline. Urümqi, in Muslim-majority Xinjiang, or the mountainous (and snowy) Tibetan plateau, one suspects, were off-limits due to the government’s anxiety that separatists might try to hijack the games for political purposes.

Critics note that the 2008 Beijing ceremony, like the 2014 Winter Games in Russia, did little to promote human rights, and they point to the egregious conditions of foreign workers in Qatar, which is (for now) hosting the 2022 World Cup, despite the ongoing tumult over corruption at FIFA. Handing the 2022 Games to Beijing will do just as little to influence Chinese behavior.

But there’s a strong case that Kazakhstan would have been more susceptible to international influence — it’s not a member of the United Nations Security Council, for one, and Nazarbayev has gone to great lengths to portray his rule as just, if not always liberal or democratic. He’s sensitive to international pressure on democracy and human rights, considered renaming the country to eliminate its status as ‘just one of the ‘-istans’ in Eurasia, and his government nearly went into a tailspin when a comic mock-u-mentary portrayed the country in a silly, provincial light.

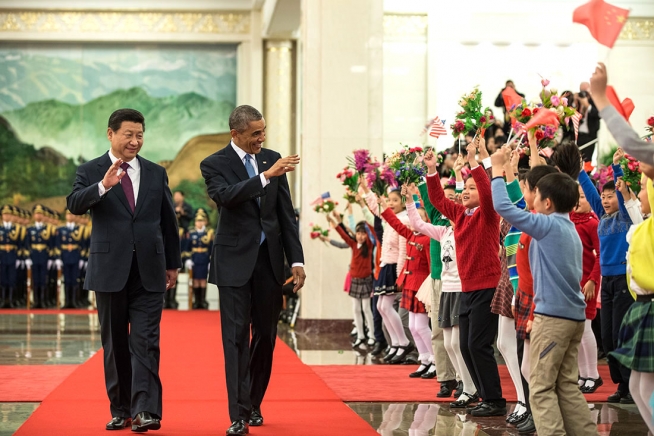

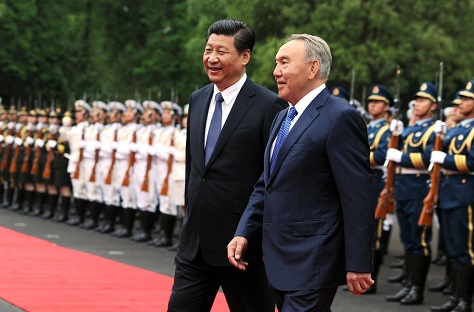

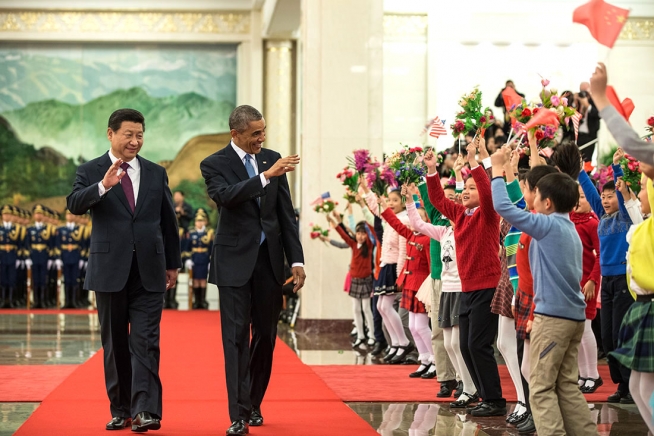

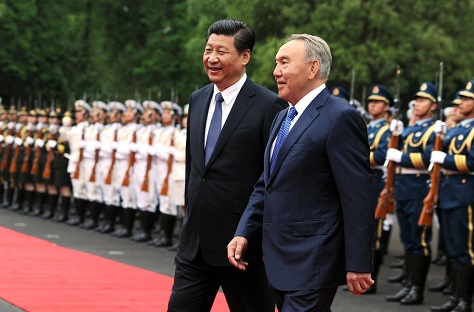

Of course, the 2022 Winter Games would have been a Nazarbayev legacy project, from start to finish, but no less than they’ll now be a showcase for China’s ruling Communist Party — in 2022, China’s leader Xi Jinping (pictured above with Nazarbayev) will be prepared to step down after a decade in power.

But they’re also a project that could have bolstered Kazakhstan’s independence and transformed the image of central Asia worldwide. It’s difficult to think of another Olympic ceremony, short of the Barcelona Summer Games in 1992, that could have had as much transformative value — not even the pending 2016 Summer Games in Rio de Janeiro, the first games to be held in Brazil or in South America.

Handing the 2022 Winter Games to Almaty would have highlighted a region with has a unique culture and a storied Silk Road history at the crossroads of world history. This more intimate understanding is precisely why the Games exist, and Beijing’s selection marks a wasted opportunity to further fundamental Olympic goals.

![]()

![]()