But as it turns out, orange is also the new bulwark for liberal democracy.

Mark Rutte’s governing center-right, liberal Volkspartij voor Vrijheid en Democratie (VVD, the People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy) performed better than polls predicted in The Netherlands, and Rutte will now return as Dutch prime minister — perhaps through the end of the decade — as head of a multi-party governing coalition.

Conversely, Wednesday’s election amounted to a disappointing result for Geert Wilders and the sharply anti-Europe, anti-Islam and anti-immigration Partij voor de Vrijheid (PVV, Party for Freedom

As Dutch voters took a harder look at the campaign, however, they turned away from Wilders’s populism and to the balmier vision of Rutte’s VVD. But they also turned to three other parties that ranged from conservative to liberal to progressive. Indeed, over 65% of the Dutch electorate supported parties that are, essentially, in favor of moderate policymaking, European integration and basic decency to immigrants.

Given that the Dutch election is the first of a half-dozen key European national elections in 2017, all of which are taking place in the dual shadows of last year’s Brexit referendum and Donald Trump’s election in the United States, everyone was watching this vote in particular as a harbinger for European elections this year.

So what does today’s result mean? Here are the top eight takeaways from election night.

1. European voters may be swinging away from populism

In June 2005, around 61.5% of Dutch voters said ‘no’ to a federal-style EU constitution (just three days after a much narrower ‘no’ vote in the French referendum). More than anything, the emphatic tegen firmly demonstrated that Dutch enthusiasm for European integration has its limits — even among tolerant voters in The Netherlands, one of the founding countries of what is today the European Union. Just three years earlier, in the 2002 Dutch election, 17% of the electorate backed supporters of the late Pim Fortuyn, an urbane and openly gay intellectual with sharp anti-immigration views, who was assassinated just nine days before the election.

Which is to say that today’s disappointing result for Wilders and the PVV wasn’t necessarily pre-ordained. It only narrowly lost to the VVD (16.1% versus 16.4%) in Rotterdam, the country’s second-largest city. But for all the talk that a new Trump-style nationalism is sweeping the developed world, Wilders fared particularly poorly, collapsing into second place. Wilders, who has led the party through four consecutive elections since 2006, won less support in 2017 than his party did in the 2010 elections (15.4%). By any measure, it’s a disappointing night for populism and ‘unreconcilable-clash-with-Islam’ nationalism.

As turnout across The Netherlands peaked far above 2012 levels, especially among young voters, Wilders’s defeat shows that Dutch voters firmly reject hard-line calls for a crackdown on immigration or a Dutch ‘Nexit’ from the European Union or the eurozone. It’s just one election, and The Netherlands is home to barely 17 million people — that’s around one-fourth of France’s population and one-fifth of Germany’s. But Wilders’s failures are a very bad sign for populist fellow travelers across Europe, including Marine Le Pen, who hopes to win the French presidency this spring against steep odds on a similar platform of pulling out of the European Union and halting Muslim immigration.

2. Mark Rutte will continue as prime minister

No one will accuse Mark Rutte of being as flashy or controversial as Wilders, but he has been a force for Dutch stability since 2010 when he first came to power.

The two governing parties, Rutte’s VVD and the Partij van de Arbeid (PvdA, Labour Party), were the only two parties to lose a significant number of seats in the 2017 election, and the VVD itself lost nearly a quarter of its seats from its 2012 result. Normally, that would be a damning statement about the direction Dutch voters wanted to turn.

Nevertheless, amid landscape where voters fractured among many parties, and no single party won much more than 21% of the vote, the VVD has enjoyed a resounding victory — beyond what even the most optimistic of polls showed before election day. Rutte has nevertheless solidified his position as the leader of the most popular party in The Netherlands.

For that, Rutte should send a thank-you card to Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, the Turkish president who spent the weekend slamming Rutte’s government for barring Turkish political rallies in The Netherlands and hysterically accusing the Dutch government of ‘nazism’ and ‘fascism.’ It may have nudged voters to support Rutte at Wilders’s expense. (Erdoğan is holding a high-stakes referendum on transforming Turkey from a parliamentary republic to a presidential one, and he hoped to stir up support among Turkish voters abroad).

As for the next Dutch government, expect much of the same — a steady hand in line with other liberal European governments of both the center-right and the center-left, continued budget discipline and perhaps modest tax relief.

3. Coalition talks could grind on for months

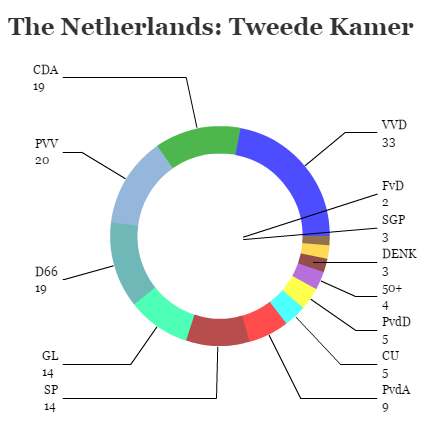

It will not necessarily be easy for Rutte to build a government, due to the fragmented nature of the new Tweede Kamer (House of Representatives), which is likely to include representatives from 13 different political parties.

It took the VVD and Labour weeks (not months) in 2012 to pull together a coalition government. This time around, it could easily take much longer. It would be surprising if Labour, which has lost nearly 30 seats from 2012, joins Rutte again in the next government. But with or without Labour, Rutte will need to negotiate a governing program to sustain a new four-party (or maybe even five-party) coalition.

Rutte has two natural allies.

The first is the Christen-Democratisch Appèl (CDA, Christian Democratic Appeal), a socially conservative, center-right party that joined Rutte’s first government between 2010 and 2012, and which dominated Dutch politics in the 2000s when the CDA’s Jan Peter Balkenende served as prime minister (indeed, the VVD served as the junior partner in two of Balkenende’s cabinets from 2003 to 2006).

The second is Democraten 66 (D66, Democrats 66), a quirky party (yes, formed in 1966) that promotes good-government reforms and center to center-left liberalism. The party belongs to the same European family of parties as the VVD and, like the VVD, it served as a junior partner in Balkenende’s cabinet from 2003 to 2006.

* * * * *

RELATED: Who is Alexander Pechtold?

* * * * *

Together, the three parties (VVD, CDA and D66) form a center-right and liberal consensus to cut income and corporate taxes, institute new limits for temporary labor contracts and perhaps even reform and simply the tax system.

But Rutte will need to find just a few more votes to get to a majority.

The conservative ChristenUnie (Christian Union) seems likeliest to join a four-party coalition. But Labour remains a potential partner. Far less likely are the pro-pensioner and populist 50PLUS or the quirky pro-animal rights Partij voor de Dieren (PvdD, Party for the Animals).

4. Expect D66 and CDA sniping to

undermine Rutte’s cabinet

Both D66 and the Christian Democrats increased their share of the vote between 2012 and 2017, and both will feel entitled to push aggressively for their interests in the next government.

But the parties’ respective leaders, each of which will be gunning for deputy prime minister or other top appointments in the third Rutte cabinet, shared a fair amount of mutual disdain during the campaign season. During one leaders’ debate, D66 leader Alexander Pechtold scolded Christian Democratic leader Sybrand Buma for his anti-migration rhetoric, warning that his party was trying to turn Muslims into ‘second-class citizens.’ At one point, Pechtold turned to Buma and told him, ‘you’ve been a big zero.’

The two parties are closer in policy viewpoints than cultural touchstones. D66 attracts wealthier and urban supporters, including a fair share of younger and middle-aged voters. The Christian Democrats, however, tend to attract older, poorer and more rural supporters. The Christian Democrats skew to a more socially conservative viewpoint than D66, and that was most evident in the 2017 election on immigration.

5. With Labour’s collapse, Eurogroup may get a new chair

Pity Labour, which joins the ranks of junior coalition partners that are subsequently punished by voters. It’s a familiar pattern in the Europe of the 2010s — the shared fate of the UK Liberal Democrats, the Irish Labour Party, the Free Democrats in Germany, and now the Dutch Labour Party, too.

Though Labour elected a new, more stridently left-wing leader in Lodewijk Asscher last December, it long ago lost many of its core supporters from 2012. After campaigning on a stridently anti-austerity platform in that election, Labour’s supporters were angered to watch Labour so readily join Rutte’s government just weeks after that election. Labour’s polling collapse began in early 2013 and just worsened from there — it was already clear during the 2014 European parliamentary elections and the 2014 Dutch municipal elections. Lower-income voters migrated to the PVV and to the Socialistische Partij (SP, Socialist Party), while higher-income voters migrated to D66 and GroenLinks

It’s difficult (though not impossible) to imagine Labour remaining in government after losing three-fourths of its seats. Labour’s losses alone amount to nearly one-fifth of the entire House. Instead, Asscher will likely work to rebuild Labour — once the dominant party of the Dutch center-left — from the opposition benches.

One of the dominoes that falls from today’s election is the fate of finance minister Jeroen Dijsselbloem, who also currently serves as president of the Eurogroup, the eurozone finance ministers. Reelected to the presidency in 2015, Dijsselbloem’s term runs through 2018. For now, Dijsselbloem will probably stay on as finance minister until the new government can be formed.

It’s possible that Dijsselbloem could stay on as Eurozone president through 2018, though it would be weird if he’s no longer the Dutch finance minister. If, as seems likely, he steps down from the role, the leading contender to replace Dijsselbloem would be Spanish finance minister Luis de Guindos, who narrowly lost the internal election against Dijsselbloem in 2015. Though the European left could block that appointment, demanding instead that the role go to the center-left, Dijsselbloem had become the face of European neoliberalism to many southerners, especially in Greece. In de Guindos, at least, Mediterranean Europe would get it own (admittedly conservative) voice at the fiscal and monetary policymaking table.

6. Jesse Klaver is the future of the Dutch left

No party improved more from its 2012 position more than GroenLinks (Green-Left), which is set to become the largest party of the Dutch left after its best-ever performance, nearly quadrupling its seats from four to 15. The Green-Left was the leading party in Amsterdam, the Dutch capital, and the second-leading party in Utrecht, the fourth-largest city.

* * * * *

RELATED: Meet Jesse Klaver — the 30-year old Dutch leader of the surging Green-Left Party

* * * * *

Much of that success is due to Jesse Klaver, the 30-year-old leader of the party who ran on a platform of realistic (if firmly progressive) policy goals, like introducing a per-kilometer car tax to reduce congestion and promoting the use of public transportation and alternative energy sources. Born to a Moroccan father and a mother of Indonesian descent, Klaver grew up in public housing and was raised chiefly by his grandparents. To the extent that the ‘new left’ of Tony Blair and Gerhard Schröder is extinct, and the traditional power of the center-left, labour and socialist movements all seem to have nothing to say about economic and social policy in the 21st century, Klaver’s vision of the progressive left looks increasingly like its future — youthful, incremental, inclusive and optimistic.

It might be tempting for Klaver to bring his party into government after its best-ever showing. But Labour’s example (and its horrific 2017 collapse) will serve as a warning to Klaver of the dangers of becoming a junior progressive partner in an otherwise center-right government. With 15 seats and a mandate among young and progressive voters, in particular, Klaver could play an important role as the leading voice of opposition to the next VVD-led government and, potentially, demolishing what’s left of Labour’s support base.

7. European voters are predictably worried about the rate of migration and the level of immigrant integration

The disappointing result for the PVV doesn’t necessarily mean that the Dutch electorate is comfortable about immigration. Rutte and Buma both imitated some of the rhetoric that Wilders used on the campaign trail about immigrants. Rutte in January proclaimed that immigrants should either ‘be normal’ or go away, harshly denouncing those who reject ‘Dutch values.’ Buma, for his part, argued that children should sing the national anthem in schools, and that the government should introduce mandatory community service for young people.

So even if Wilders lost today’s election, he has certainly influenced the language (if not the policy) of the Dutch center-right. It’s not controversial to suggest that Dutch voters have concerns about the rate of immigration into their country from outside Europe, especially after the deluge of refugees from Syria that crested in 2015, and integration of Muslim and other immigrants into Dutch culture, society and the economy is one of the great challenges for the Dutch government.

* * * * *

RELATED: Rutte’s liberals eclipse Dutch populists as voters go to the polls

* * * * *

One of the side effects of two decades of Fortuyn and Wilders railing against Islam was the emergence in the 2017 election of a new party, DENK (the Dutch word for ‘think,’ and the Turkish word for ‘equality’), founded by two former Labour Party MPs of Turkish descent that considers itself a movement for migrant and immigrant rights to promote greater equality for Turkish and other immigrants. The party will win three seats in the new Tweede Kamer, and there’s some evidence that its emergence as a new force severely hurt Labour. In Amsterdam, DENK won 7.5% of the vote, compared to just 8.4% for Labour (which easily won Amsterdam five years ago with 35.8%). In Rotterdam, DENK won 8.1% to just 6.4% for Labour.

8. Dutch economic policy has been a success

By and large, the result is pretty much exactly what you would expect for a country that’s among the wealthiest in Europe with a strong, competitive economy, relatively low unemployment and world-leading health and social indicators. There’s no reason to believe that Dutch voters wanted to upend their government or that they were clamoring for a Trump-style rupture.

It’s boring to say, perhaps, but sometimes voters realize there are limits to what government can accomplish — and there are benefits to empowering centrists and moderates who are often more boring than flamethrowers like Wilders. The economy is on the upswing, especially compared to 2012, when the eurozone crisis was fresh in the minds of voters, and Rutte was under siege to cut off Dutch support to bail out the struggling Greek economy.

Since Trump’s victory (and even before), the mountain of international press for Wilders rose steadily. Of course, Trump’s election made possible the idea of normalizing a more nationalist worldview across the developed world. But there were always alternative narratives about the Dutch election. Rutte is now one of the longest-serving leaders in Europe. Klaver is now a genuine star of the European left. Pechtold leads a party that really has no analogue in the rest of Europe, and he and Buma are now set to be more powerful than just about anyone else after Rutte.

Let me understanding this correctly. Wilders’ PVV becomes the second most voted party of the Netherlands and they are the big losers? The Dutch left imploded, pure and simple. Wilder’s has moved the Netherlands to the right,but the media doesn’t want that narrative.

@Frank, certainly not true. The left is more divided than ever (Labour, GreenLeft, D66, DENK, SP, Party for Animals, that’s 64 seats, before the elections 71 seats). VVD lost 9 seats, PVV won 5 seats, CDA won 6 seats. It’s nonsense to say the Dutch left imploded, they lost some 7 seats out of 150, that’s certainly not an implosion!