Felipe González was just 41 years old when he became, in the view of many Spaniards, the most consequential prime minister to date in post-Franco Spain.![]()

![]()

![]()

Across a span of 14 years in power, González, the leader of the center-left Partido Socialista Obrero Español (PSOE, Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party), won four consecutive elections, normalized the rule of law and the traditions of democratic participation in Spain, brought the country into what was then the European Economic Community, the forerunner of today’s European Union, and shepherded Spain into NATO as a firm member of the transatlantic military and security alliance.

Today, while Spaniards take for granted many of those accomplishments as pillars of the Spanish state, González is also now remembered for the levels of corruption that sank his final government and a botched attempt to combat armed Basque nationalists.

But he’s still the first among Spain’s elder statesmen, in many ways as influential as the former king, Juan Carlos I, who abdicated in 2014 in favor of his son Felipe VI. In truth, the two are more responsible than anyone for Spain’s vibrant democracy today.

Third election a Christmas miracle?

As his country enters its 10th month without a government, voters may worry that Spanish democracy has become a bit too vibrant in recent years, as a strong two-party political system has crumbled into a four-party state with myriad regionalist parties from all corners of Spain, its two-party system dissolved under the penumbra of depression-level GDP contraction and unemployment.

That’s why, after two elections, the first in December 2015 and the second in June 2016, no party can quite cobble together the necessary majority to form a government. If Spain’s party leaders cannot unlock a breakthrough by the end of October, the country will head to the polls for the third time in 13 months, possibly even on Christmas Day 2016.

González, who has doled out criticism for all of Spain’s political leaders, is one of the few PSOE figures publicly urging his party and its young leader, Pedro Sánchez, to concede its fight to deny another government under conservative prime minister Mariano Rajoy. In his view, Spain would suffer greater damage from a third general election in 13 months — as polls show that yet another snap election would result in essentially the same deadlock as the last two. In a country where turnout of 75% or more isn’t uncommon, turnout dropped from 69.7% in December to just 65.7% in June, and it could fall even lower, to 63% or worse, with another snap vote. Generally speaking, Spanish observers believe that will boost the PP, at the expense of the PSOE and Podemos, the leftist, anti-austerity movement that formed in 2014 out of the indignados movement of Spain’s masses of unemployed workers.

* * * * *

RELATED: PSOE’s incentives point to PP-Ciudadanos minority government in Spain

* * * * *

Another election in Spain would come as both Germany and France face national elections in 2017 with rising eurosceptic sentiment. It would come weeks after a make-or-break referendum on constitutional reform that’s seen as a plebiscite on Italian prime minister Matteo Renzi, and as the United Kingdom, under its new prime minister Theresa May, maneuvers to leave the European Union after its blockbuster June 2016 ‘Brexit’ vote. It could fall just days after the United States might elect businessman and reality television star Donald Trump as its next president.

So the last thing Spain’s leaders (and European and American leaders) want is another inconclusive vote and prolonged uncertainty that could threaten the slight economic growth that Spain’s generated in 2015 and 2016 and that has left the country without a government to implement a budget for the next year or provide leadership in ongoing post-Brexit debates over the European Union’s future.

Rajoy fails to win investiture vote

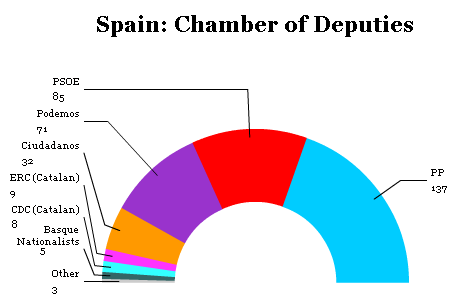

The latest despair comes after another failed attempt by Rajoy to retain power. Although his conservative Partido Popular (PP, the People’s Party) won the greatest number of seats in the most recent June election (indeed, a 14-seat increase from the December election), he has twice failed to win two confidence votes since the end of August, with a majority of the Chamber of Deputies (Congreso de los Diputados), the lower house of the Spanish parliament, blocking Rajoy’s investiture.

That’s despite building an alliance with Ciudadanos, a reformist, federalist and economically liberal party that recently, under the leadership of 36-year-old Albert Rivera, has emerged as a national force (after years of contesting local elections in Catalonia). That, with the support of another Canary Islands deputy, gives Rajoy 170 votes, just short of a majority.

It hasn’t helped that Rajoy refuses to step down in favor of a more conciliatory or moderate figure as prime minister, and it also doesn’t help that Rajoy’s party is mired in corruption scandals.

Rajoy’s failure now gives Sánchez, an economist and political neophyte who unexpectedly won the party’s leadership in the summer of 2014, an outside chance to become prime minister. Despite common ground with Ciudadanos (Rivera negotiated a similar package with Sánchez before the June elections) and even with Podemos, attempts to create a three-party coalition failed last spring.

The negotiations fell apart when Sánchez refused to grant a request from Podemos to allow a constitution referendum on Catalan independence. Neither party’s policy lines have moved since the spring, and given that the three parties together hold even fewer seats than after last December’s vote, such a coalition seems far more unlikely today.

With regional elections looming in two fiercely independent northern communities on September 25 — Galicia and the Basque Country — and with the Socialists likely to suffer losses in both contests, Sánchez will face more pressure than at any time in his troubled leadership.

Essentially, Sánchez faces four choices:

- join a grand coalition government with the PP (as in Germany),

- cobble together a coalition of the left (as in Portugal),

- abstain and allow a PP minority government to proceed, or

- block a PP government and allow a third set of elections.

Given the political pressure not to enable another term of conservative rule, it’s very nearly politically impossible for Sánchez to join a government alongside Rajoy (or even under a slightly more moderate PP prime minister). Moreover, as noted above, a three-party coalition with Podemos and Ciudadanos seems far-fetched.

That leaves Sánchez with two realistic (and unappealing) options. Either he can strategically permit a Rajoy-led minority government to take power or he can gear up for Christmastime elections that would certainly bring depressed turnout at a time when many Spaniards (especially those in PSOE-supporting urban enclaves) will be traveling and unable to vote.

Nearly half of his party, including González and another former prime minister, José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero, have called on the PSOE to abstain from a vote of confidence, thereby permitting a minority coalition between Rajoy’s party and avoiding new elections. The reasons are clear enough. Sánchez could credibly argue that a third set of elections over the holidays, given the polls that forecast another stalemate, are a needless waste. Besides, Spain needs a government, and the Partido Popular has the strongest claim to a mandate. At any time, however, the Socialists could pull the plug on the minority government if they believe they could win an election. After a year or two of additional budget austerity and lumbering unemployment, a PSOE government may seem much more amenable to Spanish voters.

The other half of the party believes that propping up Rajoy is tantamount to political suicide and would amount to policy abdication. Permitting Rajoy and Spain’s conservatives, even by default, to continue implementing deep budget cuts and tax increases that have depressed Spain’s economic potential, would send leftist voters toward Podemos, giving it the boost it needs to overtake the PSOE. Podemos leaders, such as academic Pablo Iglesias, seem delighted anyway for a third chance to overtake the PSOE as Spain’s most popular leftist party.

So far, regional presidents such as Susana Díaz, the leader of Andalusia, and Ximo Puig, the leader of Valencia, have not made any strong public statements, but they are suspected to agree more with González than with their own party faithful about a third Spanish election. Díaz, in particular, may harbor leadership ambitions of her own, and party bosses, Severe losses in Galicia and the Basque Country may force Sánchez’s resignation, but his firm stand against Rajoy’s investiture has boosted his support among the grassroots. (PSOE leaders are determined by popular contest, just as Labour’s leaders in the United Kingdom are determined).

Basque Country: Regional parties thrive while PSOE falls to fifth?

It wasn’t too long ago that the local branch of the PSOE held power in the Basque Country under regional president (in Basque, the lehendakari) Patxi López. That changed in the most recent 2012 elections with the resurgent Partido Nacionalista Vasco (PNV, EAJ, the Basque Nationalist Party or, in Basque, the Euzko Alderdi Jeltzalea), which now holds power in the Basque Country as the more moderate of two Basque national blocs, leading a minority government currently propped up with PSOE votes.

When voters elect a new Basque regional government on September 25, polls show they will continue to reward the PNV-EAJ and López’s successor, Iñigo Urkullu, with a strong win of between 34% and 38%.

As in 2012, Euskal Herria Bildu (EHB, Basque Country Unite), a more radical coalition of abertzale, the pro-independence Basque national leftists (with politics that once animated the ETA’s armed struggle) are likely to win second place, with between 20% and 21% of the vote. Unlike in 2012, however, a coalition of Podemos-led leftists seems set to win third place (or even nudge their way into second), with between 18% to 19% of the vote. That would send the PSOE to fourth or even fifth place, behind the Basque branch of the People’s Party. After winning 18.9% of the vote in 2012, polls today show the local PSOE would win just 11% or 12%.

Urkullu only needs a simple majority to retain control over the Basque executive, but if the abertzale and the Podemos-led coalition do well enough, he might need both the PP and the PSOE to retain power. The risk for Sánchez isn’t so much that the local Basque socialists will be embarrassed (though polls show they will be), but that Rajoy might demand support from the PNV-EAJ’s five deputies in Madrid in exchange for PP support backing Urkullu.

Galicia: Continued PP dominance

In Galicia, the stakes are lower.

Everyone expects the People’s Party to win with ease, as it is currently polling between 43% and 45% of the vote. The Socialists, by contrast, have never won an election in Rajoy’s home base of Galicia, a conservative stronghold in northwestern Spain. The PSOE’s best result was winning 33.2% of the vote back in 2005, which allowed it to form a one-term coalition government with the Bloque Nacionalista Galego (BNG, Galician Nationalist Bloc), a Galician interests party.

Though the PSOE is today polling at around 18% to 21% of the vote, nearing its worst-ever result of 19.5%, that’s not far off from the most recent 2012 election (20.6%). It’s even a considerable moral victory in light of the rise of Podemos and the hard left across Spain.

In Galicia, longtime leftist parties have joined forces with Podemos to form En Marea (In Tide), and they are polling between 20% and 25% of the vote. The BNG, which has faced internal splits since 2012, when it adopted a more eurosceptic and pro-independence stand, is struggling far behind in fourth place, with between 5% and 7%.

Viewing Spain’s current situation they need reforms urgently. Euro is going downward spiral!