The headline from Sunday’s Portuguese parliamentary election results highlighted the fact that the country’s center-right government won despite the fact that it implemented an unpopular bailout program that entailed difficult spending cuts and tax increases.![]()

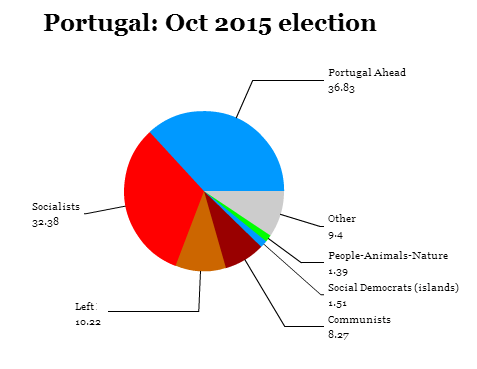

That’s true, of course, and the electoral coalition of prime minister Pedro Passos Coelho did emerge with the largest share of the vote. Later this week, it’s expected that he will receive a mandate to form a new government from Portugal’s president Aníbal Cavaco Silva.

*****

RELATED: Portugal holds first post-bailout elections

*****

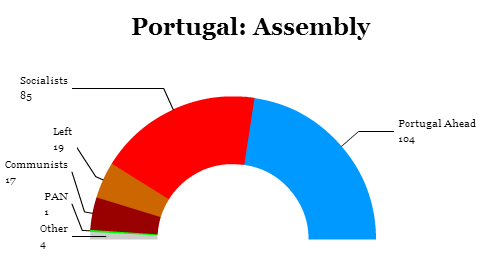

With neither of Portugal’s mainstream parties able to win a majority of seats in the country’s 230-member, unicameral Assembleia da República (Assembly of the Republic), early elections seem certain to follow in due course. Though it’s likely that Passos Coelho’s center-right coalition, Portugal à Frente (Portugal Ahead) will indeed form a minority government, it will need the support of its chief opponent, the center-left Partido Socialista (PS, Socialist Party) to pass next year’s budget and other key measures. With the country no longer subject to the term of its prior bailout program, and with the economy set to grow for the second consecutive year in 2015, the Socialists will almost certainly demand a high price in exchange for support, including some relief from the austerity measures of the past half-decade.

A disagreement, however, could lead the country to a snap vote, perhaps as soon as next summer. While no new elections can follow for six months, no minority government since the end of the Salazar-era military dictatorship in 1974 has been able to hold onto power for a full four-year term.

In truth, no one won Portugal’s elections, and turnout dropped from 5.59 million (around 58%) in 2011, then a record low since the return of democracy, to just 5.38 million on Sunday (around 57%). The center-right’s ‘victory’ is as Pyrrhic as they come, the center-left’s modest gains belie doubts about past performance, and radical leftists haven’t received the same welcome as in crisis-struck Spain or Greece.

In one sense, the Socialists were the biggest losers of the election. Just a few months ago, they were on course to win an outright majority. Despite the charisma of their new leader, former Lisbon mayor António Costa and the Socialists’ more full-throated, anti-austerity shift under his leadership, the party’s 4.4% share increase wasn’t enough for victory. That’s a disappointment, but Costa will remain leader (for now at least), hoping that a fresh vote will push the Socialists back into power.

But the Socialists were actually in power when Portugal first requested a bailout, and it was former prime minister José Sócrates who initiated the cycle of spending cuts and tax increases. The debt crisis began when the Socialists were in power, and they own the bailout and its consequences nearly as much as Passos Coehlo. The fact that Sócrates is under house arrest pending trial for corruption did not do any favors for the Socialists, either.

Left-leaning voters had no shortage of options, and they flocked to them in high numbers, by Portuguese standards — though not nearly as strongly as in Greece, Italy and, if polls are correct, in Spain’s December national elections. The anti-austerity Bloco de Esquerda (Left Bloc) had its best performance since its 1999 foundation, winning just over one-tenth of the vote, and the Coligação Democrática Unitária (CDU, Democratic Unitarian Coalition), a coalition of the Portuguese Communist Party and Portugal’s Green Party had its best result since 1997. Together, the far left will hold 36 seats in the new assembly, but the Socialists will by no means want to alienate moderate supporters by joining a radical left coalition. Though the far left’s successes were slightly surprising, the Left Bloc finished only slightly behind its 2009 total, and the two mainstream parties still won two-thirds of the vote.

Before the next election, the challenge for Costa will be to show moderate voters that he can be reasonable in working with a center-right government while also proving to leftist voters that the Socialists can force looser fiscal policy.

Passos Coehlo benefited from an improving economy and lower unemployment as voters watched in dismay while Alexis Tsipras’s far-left government in Greece wrecked the country’s nascent recovery in a failed bid to negotiate more lenient terms from its lenders.

But the center-right has no reason to gloat. The challenge for Passos Coehlo will be to hold his coalition together long enough to ride into what will (hopefully) become a robust economic recovery. Though the previous government joined forces formally for the election, there’s no guarantee that his party, the Partido Social Democrata (PSD, Social Democratic Party) will remain merged with their more conservative partners, the Centro Democrático e Social – Partido Popular (CDS-PP, Democratic and Social Center — People’s Party). Deputy prime minister and foreign minister Paulo Portas is a wily and experienced politician, and he nearly ended the last government when he briefly resigned in the summer of 2013.

Moreover, the center-right coalition won just 36.8% of the vote. That somewhat understates its support because the Social Democrats were on the ballot by themselves in the Azores and Madeira, adding another 1.5% to their national totals. Still, together, with the most generous count, the coalition in 2015 won less (38.3%) than the Social Democrats won alone in the 2011 elections (38.7%). It was a smart move, at least on optics, because the Socialists might have ‘won’ the election if the Social Democrats and the CDS-PP were competing separately.

Nevertheless, had the two parties run on a joint ticket in 2011, their combined total would have been 50.4%. That’s still a brutal fall in support for a government that wants to claim ‘victory’ after Sunday’s election.

In the long run, Portugal will face an economy that was having trouble throughout the 2000s and long before the global financial crisis or the European debt crisis. In the last five years, around 500,000 Portuguese have left the country in search of work, and there’s no sign that the outward migration trend will necessarily end, even if it slows.