Chart credit to Bank of America.

Chart credit to Bank of America.

Within a half-century, the most important fact of the Obama administration might well be that it presided over an energy boom that de-linked, for the first time in many decades, US dependence on Middle Eastern oil and foreign policy.![]()

![]()

No other fact more explains the deal, inked with the Islamic Republic of Iran, that brings Iran ever closer into the international community — and no other fact brings together so neatly the often contradictory aspects of US president Barack Obama’s policy in the Middle East today.

* * * * *

RELATED: Winners and losers in the Iran nuclear deal

* * * * *

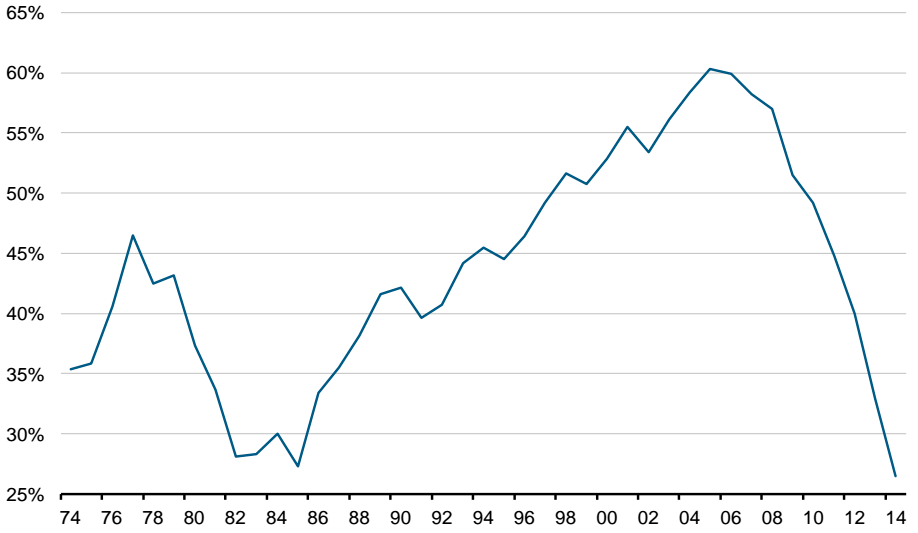

With the exception of a small peak in the mid-1980s, when prices tanked after the oil shocks of the 1970s, US imports of foreign oil are lower than ever — and that’s a critical component to understanding Tuesday’s deal between the P5+1 and Iran. Thanks, in part, to the shale oil and fracking revolutions, US oil reserves are at their highest levels than at any point since 1975. Bank of America’s chart (pictured above) shows that US dependence on foreign oil — net imports as a percentage of consumption — dropped to 26.5% by the end of 2014.

Making sense of the Obama administration’s Mideast contradictions

One of the sharpest criticisms of the Obama administration is that it has no overweening strategy for the region. On the surface, the contradictions are legion. To take just three examples:

- The administration jumped (probably too soon) to help Libya’s rebels oust Muammar Gaddafi in 2011. Nevertheless, it refrained from intervening to oust the bloody regime of Syria’s Bashar al-Assad, even after members of the Assad regime may have used chemical weapons in 2013, crossing Obama’s famous WMD ‘red line.’

- Obama celebrated the overthrow of Egypt’s president Hosni Mubarak and Tunisian president Zine El Abidine Ben Ali. But the administration did little to boost Mubarak’s democratically elected successor, Mohammed Morsi, and it has worked to develop strong ties with Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, who ousted Morsi in a military coup and who has arguably violated more human rights than Mubarak.

- The administration has satisfied neither doves nor hawks with its approach to the Islamic State group. Obama has deployed enough US military advisers to bring the United States back into the Iraqi theater, especially after ISIS militants nearly massacred the Yazidi religious minority and beheaded a series of Western journalists. But critics argue the US response hasn’t given Kurdish Iraqis and Syrian Sunni opponents enough support in their fight against ISIS’s growing so-called caliphate.

That’s to say nothing about the ongoing negotiations over Iran’s nuclear energy program, the administration’s tangled relationship with Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu and a generally absent strategy with respect to tiny Lebanon, struggling to maintain its own stabliity and unity, even while inundated with over 600,000 Syrian refugees. The Obama administration has been seen to deliver uneven responses to Qatari human rights abuses (in the prologue to the 2022 World Cup), the Houthi uprising in northern Yemen and growing fervor for independence in southern Yemen, a hotbed of al-Qaeda sympathy.

It’s understandable why critics say that this administration is rudderless.

But there’s another way of looking at Obama-era foreign policy that smooths out much of the jagged edges of its approach to the Middle East — namely that many of the conflicts listed above, however tragic or destabilizing they might be, no longer affect the US national interest in the same way as they would have even five or 10 years ago.

Energy independence changes the rules of Mideast engagement

The predominant reason that the Middle East increasingly held an important role in US foreign policy for the last four decades is simple — the United States needed, to the extent possible, regional stability (or at the very least, tense regional balance) to promote predictably stable oil prices. There are other reasons, including the special bilateral relationship with Israel and, especially after 2001, efforts to prevent or discourage future terrorist attacks on the United States. But the centrality of US reliance on Middle Eastern oil, in particular, meant that the United States had to cozy up to Saudi Arabia, one of the leading global oil suppliers. The Saudis produce 9.7 million barrels per day (by contrast, the world’s current leader, Russia, produces around 10.1 million, and the United States now produces around 9.4 million).

That far outpaces Iraq’s 3.4 million, Iran’s 3.1 million, the United Arab Emirates’s 2.8 million and Kuwait’s 2.6 million.

Over the years, four major events made the United States even more dependent on Saudi goodwill — (i) the steep rise in oil prices in 1973-74 resulting from OPEC action, (ii) the fall of the US-backed Iranian shah in 1979 and the rise of the fiercely anti-American Islamic Republic, (iii) the ensuing war between Iraq and Iran in the 1980s and (iv) the firm US break with Iraq in 1990-91 over Saddam Hussein’s attempted annexation of Kuwait.

Accordingly, the Carter, Reagan, Bush I, Clinton and Bush II administrations were all essentially forced to rely in large part on Saudi Arabia — doubly so when Iran’s Islamic Republic and Saddam-era Iraq ultimately became antagonistic to the United States. Moreover, 2003 invasion and subsequent occupation of Iraq, by highlighting the divisions among Sunnis, Shiites and Kurds and enabling the corruption of Iraqi prime minister Nouri al-Maliki, weakened Iraq to the point of state failure.

So for decades, Saudi Arabia was the only game in town, and it maintained its alliance with the United States through the shrewd diplomacy of Saud al-Faisal, the longtime Saudi foreign minister (who served in the role from 1975 to 2015 before his death last week) and Bandar bin Sultan, the longtime Saudi ambassador to the United States. Both princes, Saud and Bandar, became trusted — and even wise — advisers to Democratic and Republican administrations alike over the years.

Sectarian violence has only highlighted the

regional ‘cold war’ between Saudi Arabia and Iran

The Sunni House of Saud and the Shiite Iranian regime have also, for decades, been locked in a struggle for dominance throughout the region. Violence in Iraq and the Syrian civil war are adding a sharper edge to that fight by highlighting the region’s sectarian schism between Sunni and Shia Islam. Today, the Sunni-Shiite split runs deeply through each of the region’s most troubled areas — so much so that scholars argue that the Middle East is currently undergoing its own version of the Thirty Years War, the struggle between European Catholics and European Protestants. The European conflict ended only with the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, which separated religious and civic duties and brought forth the modern notion of the nation-state.

It’s too simplistic to distill the complex network of Middle Eastern relationships to the Sunni/Shia divide — the Saudis are nearly as wary of democratically elected Sunni regimes (Morsi’s Egyptian government, Turkey’s Islamist government and the Hamas-led government in the Gaza Strip) as of its rivals in Tehran. Iraq’s defining struggle today is as much between moderate Sunnis and ISIS as between Sunnis and Shiites, generally. Divisions among the myriad Sunni opposition groups are one reason why Assad essentially won the Syrian civil war. For years, the Saudi kingdom worked alongside Yemen’s former president Ali Abdullah Saleh, who unified Yemen as a single country in 1990. Saleh belongs to the Zaidi Shiite sect — about as close to Sunni as any variant of Shi’a; today, however, Saleh is boosting the efforts of the Iranian-supported Houthi rivals.

But that complexity is just another reason why the United States need not take a leading role in every Middle Eastern crisis. Plagued by dependence on the region’s oil, the United States had no choice but to take Saudi Arabia’s side — most especially its struggle against Iran.

That, of course, highlighted certain inconsistencies between American rhetoric and realpolitik. The House of Saud, since the 1700s, has been entangled in a symbiotic relationship with the peninsula’s radical Sunni Wahhabist clerics. Though there’s some truth in the ‘Saudis in Audis’ stereotype of Saudi nationals who indulge secular delights abroad, the Saudi kingdom has enforced an Islamic code of conduct at home no less severe than that of Iran’s mullahs. Women’s rights, arguably, are even more restrictive in Saudi Arabia, where women still cannot drive. Iranian democracy may bear little resemblance to Western-style democracy, and the 2009 election may have shown the system’s corruptibility, but Iran remains far more democratic than Saudi Arabia. Most damning of all, the Saudi kingdom spawned not only al-Qaeda and Osama bin Laden, but it famously supplied 15 of the 19 hijackers that brought down airplanes in Washington, D.C. and New York City in 2001. Former president George W. Bush’s second inaugural address is full of cringe-worthy, absolute declarations about defending freedom and standing with democratic reformers that stood in stark contrast with decades of complicity (including his own administration’s) with Saudi brutality.

Serving the US national interest on an ad hoc basis

But the brilliance of the Obama administration’s Middle East strategy lies in the flexibility that no longer chains the US national interest to monolithic alliances. Unfettered from reliance on foreign oil, the US government can pick and choose its battles, using a mix of military, economic and diplomatic tools to extract the maximum benefit for US priorities. If the Saudis and the Iranians want to spend money, time and lives engaged in proxy fights over Yemen (or Bahrain or Syria or Lebanon or wherever), it’s not necessarily a US problem anymore.

Arguably, US heavy-handedness in the region has made the United States a greater target for radical Islam. That dates back to its role in overthrowing Iran’s popular prime minister Mohammad Mosaddegh in 1953. But it also includes the US role in regional conflicts among Jordanians, Israelis and Palestinians that culminated in Lebanon’s civil war of the 1980s. It includes US support for brutal Iraqi assaults on Iran (complete with chemical weapons) in the 1980s. It includes the abuses and failures of dual occupations in Afghanistan and Iraq in the 2000s. The Obama administration, too, is guilty of civilian deaths caused by unmanned drone attacks on suspected terrorist targets in Yemen, Somalia, Pakistan and elsewhere. Were US soldiers and US bombs responsible for less Muslim deaths, it would become a lot more difficult for jihadists to convince young Arabs that they should blow themselves up in the name of vengeance against the United States.

For the first time in generations, the Obama administration has enjoyed the freedom to distance itself from the region’s bloody conflicts. For years, it was vital to maintain a united front against Iran from a geostrategic standpoint. But in a world where the United States no longer needs to curry favor with Saudi Arabia to prevent it from bringing the US economy to its knees, it makes sense that the US government can — and should — approach alliances on an ad hoc basis. It’s already clear that the United States and Iran are functionally allies against ISIS in Iraq and Syria. For all the rhetoric denouncing the Iranian-funded Hezbollah, the Shiite militia serves, to some extent, as a stabilizing force in southern Lebanon and Syria. A complex region requires a correspondingly complex approach — especially when outside influences try to force the US government to choose between a bad option and an even worse option (e.g., the Assad government and Salafi radical rebels in Syria).

That’s exactly why the deal with Iran is such an important milestone in US foreign policy.

It announces that, while the United States may still have its share of difficulties with, say, Iran over human rights, Iran’s regional shenanigans and the country’s longstanding hostility to Israel, the US government can still partner with Iran to find a workable solution that lifts international sanctions, permits Iran to develop its nuclear energy capability and that will simultaneously monitor and punish any attempted to develop nuclear weapons.

All of this becomes possible in a world of US energy independence — and though the Iran deal, in particular, has become a hot-button issue in American domestic politics, there’s every reason to expect that the next presidential administration, Democratic or Republican, will cherish the new, more liberating, 21st century rules of engagement in the Middle East.