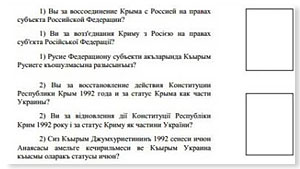

The global media’s attention this weekend will be fixed on Crimea, where a status referendum is almost certainly likely to result in its annexation into the Russian Federation.![]()

![]()

But the world’s attention should be on Serbia, which is holding snap elections on March 16 — the same day as the Crimean referendum. Serbia’s parliamentary elections come just two months after formally opening negotiations to join the European Union, a landmark step in what’s been a decade-long push for greater Serbian-EU integration.

When political commentators tell you that Ukraine is the frontier of the European Union, they’re right that European policymakers have both an economic and security interest in Ukraine’s stability.

But the true frontier of the European Union is the Balkans, and no country is more vital to the future political and economic stability of the region than Serbia, home to over 7 million residents, the most populous of the Balkan states.

Polls show that the outcome of Sunday’s election is almost certain — a wider majority for the center-right Serbian Progressive Party (SNS, Српска напредна странка), which as a member of the current coalition government, is working to tackle corruption, liberalize and privatize sectors of the Serbian economy and bring Serbian budget closer to balance — all while the country faces unsteady economic growth and an unemployment rate of 20%.

Notwithstanding the real economic pain today in Serbia, none of that matters as much as the fact of Serbian continuity with respect to European integration. Though Serbia’s formal accession may take up to a decade, Serbia seems certain to become either the 29th member (or the 30th member, following Montenegro) of the European Union. What’s more, the most significant fact of Serbian political life in the past two years has been the durability of the national commitment, across all major political parties and ideologies, to Serbia’s eventual EU membership.

Think back to the breakup of Yugoslavia in 1991. Or to the ‘ethnic cleansing’ that marked the civil war among Croats, Bosnian Muslims and Serbs between 1992 and 1995 in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Or to the Serbian aggression over Kosovo that led to NATO military action against Belgrade in 1998-99 and the emergence of the semi-independent Kosovo today. Or to the dictatorship of Serbian strongman Slobodan Milošević from 1987 until 2000, with full-throated support from Moscow.

Though it’s something that we take for granted in the year 2014, it wasn’t always a foregone conclusion that Serbia today would be so united in its push to turn economically and socially toward Europe.

It wasn’t even so clear in 2012.

Nikolić and Dačić: an unlikely pair of EU champions

In the last parliamentary elections in May 2012, the SNS won the greatest number of seats (73) in Serbia’s 250-member National Assembly (Народна скупштина), and the SNS’s Tomislav Nikolić, running for the fifth time, narrowly won the Serbian presidency over incumbent Boris Tadić, whose center-left Democratic Party (Демократска странка / DS) had governed Serbia since 2004. Tadić, throughout the 2000s, laid the groundwork for greater cooperation with the European Union.

When Tadić lost power in July 2012, no one knew whether Nikolić and the Serbian Progressives would pursue EU cooperation with the same zeal as the Democrats had. Nikolić (pictured above, right, with EU foreign affairs high representative Catherine Ashton, middle, and prime minister Ivica Dačić, left) long favored Russia over the European Union, and his first trip abroad as president was to Moscow, where he declared in September 2012, ‘The only thing I love more than Russia is Serbia.’ Continue reading The most important EU success story you’ve never heard? Serbia.