The most underreported aspect of the current crisis over the Crimea annexation is the extent to which Russia was willing to go to the brink of international crisis for the goal of a future trade bloc. ![]()

![]()

Why does Russian president Vladimir Putin care so much about the vaunted Eurasian Union, even though it’s a rewarmed version of the existing economic customs union among Russia, Belarus and Kazakhstan?

To turn Michael Corleone’s words on their head, ‘it’s personal, not business.’

Putin hoped that the revamped union could attract a few more stragglers in central Asia, Azerbaijan or Armenia and perhaps Ukraine — until February 22.

There are certainly potential gains from greater free trade, and negotiating multilateral trade blocs seems both more efficient than one-off bilateral agreements and more productive than pushing for greater global integration through the World Trade Organization (WTO) process.

Also unlike bilateral treaties or WTO-based agreements, regional trading blocs are also emerging as strategic geopolitical vehicles for advances regional agendas that have just as much to do with politics as with trade.

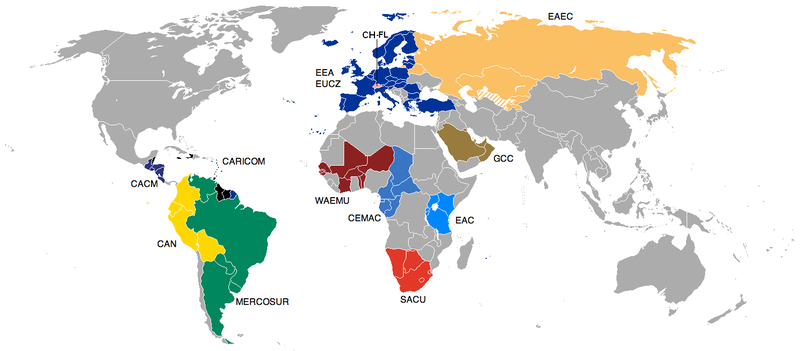

Ultimately, it’s same reason that the two South American customs unions, the Mercado Común del Sur (MERCOSUR, Suthern Common Market) and the Comunidad Andina (CAN, Andean Community) joined to form the even larger Unión de Naciones Suramericanas (UNASUR, Union of South American Nations), which came into existence in 2008 and covers the entire South American region.

It’s the same reason that Kenyan president Uhuru Kenyatta has put so much pressure on Tanzania to choose between the East African Community (EAC) or the Southern African Development Community (SADC) over the past year by accelerating plans for greater political cooperation within the EAC — with or without Tanzania. Or why admitting South Sudan into the EAC back in 2011 could have helped prevent its slide into civil war.

It’s the same reason that defining ‘Europe’ has been such a strategic and existential issue for the European Union and its predecessor, the European Economic Community, since its inception. Does the United Kingdom belong? (In the 1960s, according to French president Charles de Gaulle, it didn’t). How to handle Turkey? (Enter into a customs union with it, then slow-roll accession talks since 1999, apparently). Should Ukraine join? Moldova? Georgia? If Azerbaijan can win the Eurovision contest, why not bring it into the single market? What about, one day, Morocco and Tunisia, which both have association agreements with the European Union?

That’s why it’s worth paying close attention to the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), but also the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP). TTIP would create a super-free-trade-zone between the United States and the European Union, which together generate between 45% and 60% of global trade.

In his second term, US president Barack Obama has worked feverishly to build momentum for both the TPP and TTIP, notwithstanding a relatively unambitious first-term trade agent that only sleepily turned to winning ratification for bilateral trade agreements with Colombia, Panamá and South Korea.

Moreover, the showdown between Russia and the European Union and the United States gives both Europeans and Americans a stark reminder of the importance of the trans-Atlantic relationship. Russia’s aggression in Ukraine also reminded policymakers in the United States and the European Union that trade and security can be related. This week, while Obama is in Europe this week discussing NATO, security and Ukraine, the US Congress is holding hearings on new laws liberalizing the export of liquified natural gas.

The Crimes crisis has given TTIP new urgency and, perhaps, new momentum on both sides of the Atlantic.

In a world where the United States has a surplus of natural gas, thanks to the shale oil boom and new technologies like fracking, it makes sense for the United States export more of its natural gas, despite longstanding laws largely restrict such exports, pending review from the US Department of Energy. By eliminating regulatory barriers, the United States could gain from greater energy exports and Europe (especially countries in Central and Eastern Europe) could gain by reducing its energy reliance on Russia.

Far from the vagaries of ‘country of origin’ standards, harmonization schedules and the technical jargon of the WTO’s technical barriers to trade agreements (TBT) and sanitary and phytosanitary agreements (SPS), this is hard power at its finest.

But TTIP could wield potentially larger gains. As tariffs between EU countries and the United States are already relatively low, TTIP won’t be considered a success unless it can achieve deep cuts in regulatory barrier to trade. For example, while the 2007 EU-US Open Skies Agreement liberalized transatlantic air routes (i.e., a Dutch carrier flying between Dallas and Houston or an American carrier flying between Raleigh and London), a comprehensive TTIP agreement might allow an Irish carrier to fly between Milwaukee and Washington, DC or an American carrier to fly from Edinburgh to Madrid. (Though the airline industry and other interests might oppose it, you can easily see how reducing the barriers to entry would spur greater competition and lower prices for both American and European consumers.)

Economic studies, including last summer’s comprehensive report from the Bertlesmann Foundation in Germany, show that TTIP could create up to 2 million new American and European jobs, but only if TTIP effects real regulatory gains.

TTIP, in particular, could reshape the nature of global commerce in a way that no other multilateral agreement could possibly hope to achieve because of the size of the combined EU-US market. The joint US-EU regulatory standards could force third countries to conform to US/EU environmental, labor, IP and other regulatory standards in order to do business in the US-EU super-trade-zone.

That’s enough to have caused China, India and other Asian countries to begin considering their own alternative. The proposed Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) would join Japan, China and India to the existing free-trade zone of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). In a decade, the rest of the world may face an ‘economic Cold War’ of sorts, forced to choose between the US/EU regulatory standards and the Chinese regulatory standards. What’s more, we might live in a world where everyone has to meet both the US/EU and Chinese standards.

TTIP is still in its relatively early stages of negotiation — the fourth round completed just last week, with many, many more to follow. Furthermore, domestic politics in the United States and in the European Union still threaten the chances that TTIP will become law.

European elections on May 22-25 will likely return a European Parliament slightly more skeptical of TTIP, and among the next parliament’s top priorities is drafting a new data privacy directive that could pose further problems for the transatlantic relationship (and US companies like Google, Apple and Facebook). Anger over last year’s revelations of wide-ranging electronic surveillance by the US National Security Agency could also dampen German enthusiasm for TTIP.

France, which has already tried to limit the scope of TTIP by exempting audiovisual services to protect the French film and media industry, would lose the most from TTIP — economic studies show that under the imagined US-EU trade zone, Franco-German trade would be greatly displaced by increased US-German trade. That could further erode the already weakening ‘Franco-German axis’ that for decades has been the engine of European integration.

In the United States, the ‘trade promotion authority’ or ‘fast-track’ authorization that would allow the Obama administration to negotiate both TPP and TTIP without worrying about subjecting the final product to congressional debate and amendments that could wreck months (or years) of careful deliberations. That authorization doesn’t seem likely to happen in the US Senate this year, however. The day after Obama’s state-of-the-union address, Senate majority leader Harry Reid reiterated that he won’t bring it up for a vote. There’s a strong chance that will change early next year after the November 2014 midterm elections. Post-election, Reid and a Democratic majority might be more flexible. An increasingly likely Republican majority might also enact fast-track, given its historical enthusiasm for free trade.

Ultimately, if TTIP reaches its goal, it will be among the top policy accomplishments of the Obama administration.

But if there’s any lesson to take from Ukraine/Russia/Crimea this month, it’s that the gains from creating a EU-US super-trade-zone would be just as much political as economic.