Irish voters will determine on Friday whether to eliminate the Seanad Éireann (Irish senate), the upper house of the Oireachtas, Ireland’s parliament.

Before you think that this is such a transformative step in Irish governance, it’s important to keep in mind that the Irish senate doesn’t have nearly the powers of, say, the United States senate because it doesn’t have veto power over Irish legislation — at worst, the Irish senate can delay lawmaking, not bring it to a halt. Furthermore, its members aren’t directly elected by the people, leading to charges that the upper house is a wasteful, undemocratic, unrepresentative anachronism.

If, as expected, Irish voters approve the referendum, the Irish senate will cease to exist as of the next Irish general election, which must take place before 2016.

It’s one of the campaign pledges that Taoiseach Enda Kenny (pictured above) promised in advance of the February 2011 parliamentary elections that swept his liberal center-right Fine Gael into power, in coalition with the social democratic Labour Party. In an odd-bedfellows coalition, most of Ireland’s major parties support abolishing the Senate, including Fine Gael and Labour, but also the Irish nationalist Sinn Féin. Only the conservative center-right Fianna Fáil, which suffered a historic defeat in the 2011 election, opposes the referendum and prefers to retain the senate, albeit a reformed, more representative, more productive senate.

The system by which the upper house’s 60 senators are appointed is truly anachronistic — the Taoiseach appoints 11 and graduates of the University of Dublin and the National University of Ireland are each entitled to elect three senators. The remaining 43 are nominated from five ‘vocational panels’ that span the public/administrative, agricultural/fishing, cultural/educational, industrial/commercial, and labour sectors. In practice, this means that the Irish senate is where a lot of failed political candidates land. The remaining house, the Dáil Éireann, is composed of 166 deputies.

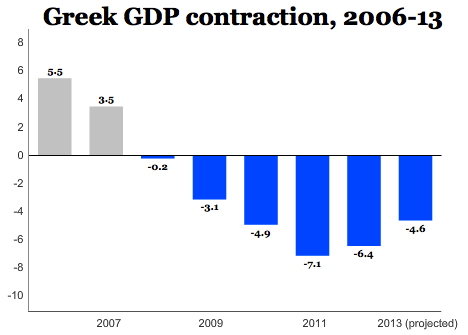

Given that Ireland has been rocked by economic crisis following the 2008-09 financial crisis that saw Ireland nationalize some of its banks and assume their obligations, Kenny and other supporters of the referendum argue that the Irish senate is an unnecessary and undemocratic expense for such a small country as Ireland (with 4.6 million people), especially in light of its 40-year membership in the European Union, which remains responsible for an increasing amount of regulatory standards within Ireland.

Many Irish voters agree — an IPSOS poll earlier this week showed 44% favored abolition, 27% opposed abolition, while 21% were unsure, though when undecideds had to choose, the pro-abolition side won 62% to 38%.

Although countries don’t abolish entire legislative chambers every day, it’s not wholly unprecedented, either. New Zealand abolished its unelected Legislative Council in 1950, Denmark abolished its upper house in 1953 and Sweden followed suit in 1970. Generally speaking, unicameral parliaments are more common on the periphery of the European Union than in its core — they exist in Portugal, all of the Scandinavian states (including Iceland), all three Balkan state, Slovakia, Croatia, Bulgaria, Hungary, Greece, Cyprus and Ukraine.

The arguments for unicameralism, generally, mirror those that Kenny and ‘Yes’ supporters are making in Ireland. Continue reading Should Ireland abolish its Seanad (Senate) and go unicameral?