Exactly one week before Germans go to the polls to choose between center-right chancellor Angela Merkel and her center-left challenger Peer Steinbrück, Bavarian voters will elect its local state government in a key test for Merkel’s regional allies.

Exactly one week before Germans go to the polls to choose between center-right chancellor Angela Merkel and her center-left challenger Peer Steinbrück, Bavarian voters will elect its local state government in a key test for Merkel’s regional allies.![]()

![]()

The outcome isn’t incredibly doubtful because since 1947, Bavaria’s staunchly Catholic, business-friendly, socially conservative Christlich-Soziale Union in Bayern (CSU, the Christian Social Union) has controlled the 187-seat Landtag, the state legislature of Germany’s second-most populous state.

Given that the state has one of Germany’s — and Europe’s — best economies, the CSU looks set to strengthen its hold on Bavarian government in what amounts to a test run of many of the arguments that Merkel hopes will power her Christlich Demokratische Union Deutschlands (CDU, Christian Democratic Party) to victory on September 22 alongside the CSU, which has been united with the CDU in federal politics for decades. Merkel, who currently governs in an alliance with the liberal Freie Demokratische Partei (FDP, Free Democratic Party), hopes that voters will give her credit for steering Germany — and the entire eurozone — through the worst of a sovereign debt crisis that began in 2010 and an economic recession from which Europe may already be recovering.

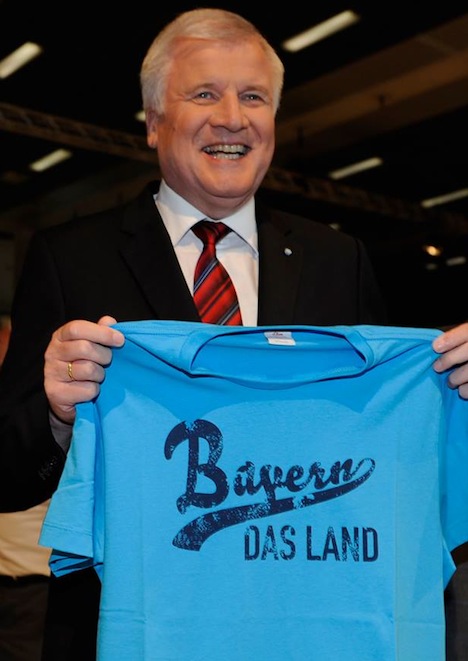

But the CSU and Bavaria’s minister president Horst Seehofer (pictured above) can make an even more sanguine case on the basis of the Bavarian economy, which showcases several star multinational corporations, such as BMW, Siemens, and adidas. Whereas the European Union had an average unemployment rate of 10.4% in 2012 and Germany had an unemployment rate of 5.5%, Bavaria’s was just 3.2%. To consider just how staggering that is, consider that United States last had an unemployment rate that low in October 1953. It’s an economy that, at around €465 billion ($610 billion), is about as large as the economy of the US state of Pennsylvania and even larger than the entire economy of Saudi Arabia, and nearly 1.5 times the size of the economy of neighboring Austria.

If the CSU is successful on September 15, it will mark a rebound from the previous September 2008 election, the CSU’s worst performance since 1954. Five years ago, Bavarian voters went to the polls in the middle of an uncertain future, with the collapse of US financial firm Lehman Brothers and a global financial panic topping world headlines. It was also a period of uncertain leadership within the CSU, Bavarian minister-president Edmund Stoiber resigned after 14 years in office following the resignation of his chief of staff, Michael Höhenberger, which itself followed accusations that Höhenberger snooped on the private life of one of Stoiber’s critics. Günther Beckstein, Stoiber’s longtime interior minister, succeeded Stoiber and led the CSU through the 2008 election, but stepped down following the CSU’s historic loss.

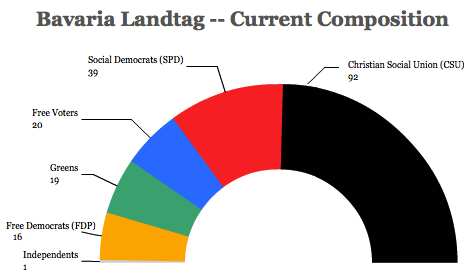

Even though the CSU won just 43.4% of the vote (a drop of over 17% from its prior performance) and lost its absolute majority in the Landtag, it remained the largest party in Bavaria by far, outpacing the second-place Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands (SPD, Social Democratic Party) by nearly 25% of the vote and Seehofer, a former health and food minister, easily won election as Bavaria’s minister-president in October 2008.

As the CSU and the SPD both suffered historic losses, two additional groups on the Bavarian right made extraordinary gains. The first is the Freie Wähler (FW, Free Voters), a bloc of independent, unaffiliated center-right deputies, which won 10% of the vote, largely from disappointed CSU supporters, and entered the Bavarian Landtag for the first time. The second is the FDP, which won 8% and 16 seats, returning to the Bavarian legislature for the first time in 14 years and providing the CSU with a stable coalition partner in Munich. Even the socialist Die Linke (The Left) competed for the first time and won 4.3%, impressive in a state as conservative as Bavaria Five years later, although polling data isn’t as ubiquitous for Bavaria’s state election as for the wider federal German elections, the CSU is polling higher than in 2008, and it may win over 50% of the vote, restoring the absolute majority that it enjoyed in the Landtag without interruption from 1962 to 2008. That’s good news for Seehofer, because the FDP is faring as poorly in Bavaria as it is in federal polling — the Free Democrats are in danger of missing the 5% threshold required to win seats in the Bavarian Landtag (and in the federal Bundestag as well). Meanwhile, the Social Democrats are in danger of setting a new postwar low in Bavaria on September 15 and in federal elections a week later — it’s polling at around 18% in Bavaria, which is even worse than its 2008 result (18.6%). It’s also good news for Merkel, who is looking for the CSU to boost her own prospects. Merkel currently governs in Berlin at the head of a CDU-CSU coalition with the FDP, but it’s uncertain that the FDP will win enough seats to allow Merkel to continue that coalition for a third term, instead forcing her to return to a ‘grand coalition’ with the SPD or a coalition with the Die Grünen (the Greens). While Merkel’s future depends primarily on the FDP, a strong CSU result in Bavaria on September 22 will boost the chances that her coalition can win a majority in the Bundestag by saturating the CDU-CSU total.

Five years later, although polling data isn’t as ubiquitous for Bavaria’s state election as for the wider federal German elections, the CSU is polling higher than in 2008, and it may win over 50% of the vote, restoring the absolute majority that it enjoyed in the Landtag without interruption from 1962 to 2008. That’s good news for Seehofer, because the FDP is faring as poorly in Bavaria as it is in federal polling — the Free Democrats are in danger of missing the 5% threshold required to win seats in the Bavarian Landtag (and in the federal Bundestag as well). Meanwhile, the Social Democrats are in danger of setting a new postwar low in Bavaria on September 15 and in federal elections a week later — it’s polling at around 18% in Bavaria, which is even worse than its 2008 result (18.6%). It’s also good news for Merkel, who is looking for the CSU to boost her own prospects. Merkel currently governs in Berlin at the head of a CDU-CSU coalition with the FDP, but it’s uncertain that the FDP will win enough seats to allow Merkel to continue that coalition for a third term, instead forcing her to return to a ‘grand coalition’ with the SPD or a coalition with the Die Grünen (the Greens). While Merkel’s future depends primarily on the FDP, a strong CSU result in Bavaria on September 22 will boost the chances that her coalition can win a majority in the Bundestag by saturating the CDU-CSU total.

Three CSU members currently serve in Merkel’s cabinet, most notably interior minister Hans-Peter Friedrich, who has taken criticism from privacy activists for his comments defending German cooperation in the U.S. National Security Agency’s PRISM program and other Internet and telephone surveillance.

The CDU and the CSU typically agree on most German issues, though the CSU, which operates in the most staunchly Catholic region of Germany, is more conservative on social issues than the CDU — it’s one of the reasons why Merkel has shied away from endorsing same-sex marriage. Differences on issues and differences between the personalities of CDU and CSU leaders have nonetheless caused significant tension within the CDU-CSU union over they years.

In the 1970s and the 1980s, West German chancellor Helmut Kohl and Bavarian minister-president Franz Josef Strauß often quarreled, with Kohl at one point threatening to run CDU candidates in Bavaria. More recently, the CSU has provided Merkel with a new set of headaches. Stoiber, who ran unsuccessfully as the CDU-CSU chancellor candidate in the September 2002 elections against the SPD’s Gerhard Schröder, only half-heartedly backed Merkel in the September 2005 elections, calling into question the ability of a female chancellor candidate to maximize votes. After Merkel selected Stoiber as her first candidate for finance minister in the ‘grand coalition’ government that followed her election victory, Stoiber suddenly changed his mind and decided to remain in Bavaria.

Though Seehofer is just as conservative and combative as Stoiber, his relationship with Merkel is at least marginally better, though he has clashed with Merkel over the past five years on everything from the local to the continental. Despite Merkel’s opposition, Seehofer has routinely called for the introduction of a car tax on non-German automobiles in Bavaria. But although Seehofer stated that he will refuse to join any post-election federal coalition that doesn’t support a foreign car levy, it is very unlikely that Seehofer would hold up Merkel’s coalition over a populist election-year issue, and Seehofer has already backed away from alienating Merkel this week.

The difference between the CDU and the CSU on Europe looms as a potentially more troublesome issue. Many CSU politicians remain less than enthusiastic about the European Union generally and German-financed bailouts to countries like Greece in particular. Bavaria’s current finance minister Markus Söder remains one of the more skeptical voices within national politics over the constitutionality of Germany’s role in providing financial assistance to peripheral European economies — he said last year that ‘an example must be made of Greece.’ CSU executive secretary Alexander Dobrindt has been equally dismissive of the European Union and Greece. Seehofer himself said last year at the heart of the eurozone crisis that the CSU’s patience for bailouts and guarantees is not infinite, and that the question of Europe might one day force a rupture between the CDU and the CSU. Seehofer has also suggested that the rest of the eurozone could survive a Greek exit from the single currency.

The split between the CDU and the CSU has its roots in 1920s Weimar-era Germany, when the Bavarian People’s Party split from the Centre Party (the predecessor to the CDU) in order to focus on a more conservative, Bavaria-focused agenda. After the end of World War II, the two parties were reconstituted as the CSU and the CDU, respectively, and have worked as a bloc in federal politics ever since, with the CSU active in Bavaria and the CDU active in Germany’s other 15 states.

3 thoughts on “Bavarian elections provides Merkel, CSU a dress rehearsal for federal German vote”