With now less than 40 days to go until Germany’s federal elections, polls show that chancellor Angela Merkel is by far the most popular candidate to return as chancellor and her party, the Christlich Demokratische Union (CDU, Christian Democratic Union), will clearly be the largest bloc in Germany’s Bundestag after the election. ![]()

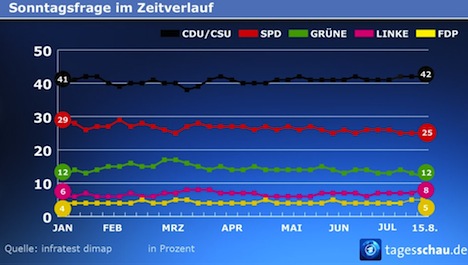

Polls have been remarkably consistent throughout much of the year leading up to the September 22 vote. The center-right CDU, together with its Bavarian sister party, the Christlich-Soziale Union in Bayern (CSU, the Christian Social Union), overwhelmingly leads Germany’s largest center-left party, the Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands (SPD, the Social Democratic Party), and voters overwhelmingly prefer Merkel to the SPD’s candidate for chancellor, Peer Steinbrück — by a nearly two-to-one margin. Here’s the trendline from Infratest dimap, which released its latest poll this week:

This week’s news that Germany leads GDP growth in the eurozone, which itself pulled out of recession in the second quarter of 2013, will only buoy Merkel’s chances. Barring a huge shift in public opinion that has only calcified over the past year, Steinbrück, a bland technocrat who comes from the right wing of the SPD and who served as finance minister in the ‘grand coalition’ government of 2005 to 2009, will lead the SPD to a loss of nearly historic proportions. But while that means Merkel is very likely to return as chancellor, the composition of Merkel’s third government is less certain.

That’s because support for Merkel’s current coalition partners, the free-market liberal Freie Demokratische Partei (FDP, Free Democratic Party), has collapsed since the previous September 2009 election, when it won 14.6% of the vote and 93 seats in the Bundestag, a record-high electoral performance for the party. But since 2009, the FDP has struggled to maintain a presence in local Germany elections, losing support in state after state. Its decade-long leader Guido Westerwelle, the first openly gay party leader in German history, stepped down in April 2011 as party leader and vice chancellor (though he remains foreign minister) after the FDP won barely 5% in the state elections of Baden-Württemberg. His successor as FDP leader is the Vietnamese-born Phillip Rösler (pictured above), who began his career in Lower Saxony (Niedersachsen) and who had served previously as health minister in the CDU/FDP coalition government from 2009 to 2011.

Although Rösler has not lifted the FDP back up to its 2009-level heights, he has managed to staunch the party’s decline. In the May 2012 elections in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany’s most populous state, the FDP managed to win 8.6% of the vote, an increase of nearly 2% from the previous election, though that’s largely due to the popularity of Christian Lindner, who led the FDP’s 2012 campaign. More recently, though, in Lower Saxony’s state election in January 2013, the FDP won 9.9% of the vote, a gain of 1.7%.

It’s also because Germany’s electoral system is notoriously complex. Germans will actually cast two votes in September — the first is for a candidate to represent one of 299 electoral districts in Germany, the second is for a German political party. The second ‘party vote’ is meant to determine the party’s ultimate total share of seats in the Bundestag, and so a party will receive additional seats on the basis of the party vote sufficient to provide that its percentage of seats in the Bundestag is roughly equal to the percentage of votes it received pursuant to the party vote (so long as the party receives at least 5% of party vote support). That means that the number of seats in the Bundestag changes from election to election — although it must have a minimum of 598 seats, it has had as few as 603 and as many as 672 since German reunification.

The FDP has struggled all year long to achieve merely 5% support in opinion polls and, while it’s doing better in polls than it was at the beginning of the year, there’s no guarantee that it will meet that threshold:

That means that, more than anything else, the composition of Germany’s next government turns on the FDP’s performance. If it wins less than 5%, Merkel will not have the option of continuing a coalition with the FDP. Moreover, even if the FDP wins more than 5%, it may still not win enough seats to cobble together a CDU/FDP majority in the 598-member Bundestag.

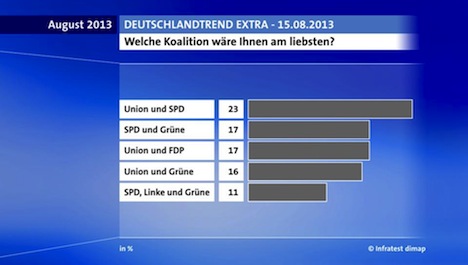

Furthermore, polls show that while German voters overwhelmingly prefer Merkel as chancellor, they actually favor a return to the CDU/SPD grand coalition, more than the current CDU-led government or a potential SPD-led government:

Two additional coalitions — a CDU/Green government and a united left coalition among the SPD, Green and Die Linke (the Left Party) — also win significant support.

But what are the chances that any of these five coalitions will actually emerge after September 22? Here’s a look at each potential coalition and the chances that it could form Germany’s next government.

The current government: CDU/FDP.

The current government: CDU/FDP.

Merkel prefers to continue her current coalition over any alternative because her political agenda matches well with the FDP’s political agenda. Any negotiations between Merkel and the SPD or the Greens would entail huge concessions from Merkel that she would not otherwise have to make in coalition with the FDP. But, as noted above (and as represented in the graph to the right, on the basis of current polls), it’s unclear if that coalition can win a majority.

Under Rösler’s leadership, the FDP is running on a campaign of lower taxes and liberalizing Germany’s economy, which is standard Free Democratic fare, and both the FDP and Merkel’s CDU oppose new tax increases. Their largest policy difference might be same-sex marriage — the FDP supports it and the CDU (and especially the Catholic-influenced CSU) oppose it, although the FDP has taken a much stronger stand on privacy rights than Merkel’s CDU.

Even if they win enough seats to form a majority, no one expects the margin to be larger than the government’s current 21-seat margin. So even a single-digit majority could turn out to be a Pyrrhic victory if Merkel finds herself forced to look outside her own government to enact her legislative agenda on an ad hoc basis, especially with respect to European Union matters, given the sometimes eurosceptic nature of many CSU deputies. That’s hardly a recipe for stable government.

Polls in August show that together, the current government will win between 44% and 47% of the vote if the election were held today. Unfortunately, that doesn’t give us much of an idea about whether they’ll have enough support in the Bundestag to form a majority. Since reunification, Germany has held only six federal elections — they’ve resulted in three CDU-led governments, two SPD-led governments and a single CDU-SPD grand coalition.

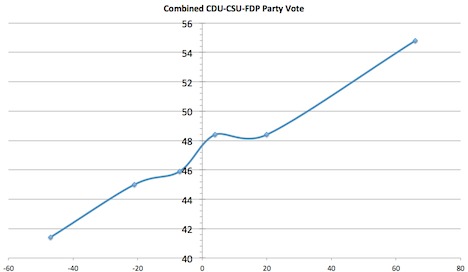

In those six elections, the combined CDU/CSU/FDP party vote has ranged from a high of 54.8% in 1990 (when in aggregate, they held a 67-seat majority in the Bundestag) to a low of 41.4% in 1998 (when they fell 47 seats short of a majority).

Here’s a graph that plots the combined CDU/CSU/FDP party vote on the y-axis against their majority (or minority) in the Bundestag on the x-axis:

It’s a little noisy, because the chart plots only the second ‘party vote,’ but the graph generally indicates that the crossover point between a minority and a majority is somewhere around 47% or so of the vote — that’s on the high end of what the current government is polling today.

In 2002, with a combined total of 45.9% of the vote, the coalition fell seven seats short of forming a majority; in both 1994 and 2009, when the coalition won a combined total of 48.4% of the vote, it ended up with five-seat and 21-seat majorities, respectively. So it’s obviously not a perfect correlation. Mark Kayser and Arndt Leininger at the Hertie School of Governance believe that the CDU/FDP coalition can win with just 45.5% of the vote, and they forecast that the CDU/FDP coalition has an 80% chance of returning to government.

It also depends on a lot of variables, including the number of votes that smaller parties win. The protest Piratenpartei Deutschland (Pirate Party) peaked at around 12% of the vote in polls in spring 2012 but today polls between 2% and 3%. The Alternative für Deutschland (Alternative for Germany) is a newly eurosceptic party founded in just February 2013, but it too polls at around 2% to 3%.

Likelihood: On the basis of current polling, it seems like a toss-up. If the CDU/CSU and the FDP win the seats, though, the coalition will easily come together.

A ‘Jamaica’ coalition: CDU/FDP/Greens.

In the event that the CDU and the FDP fall short of an absolute majority, the CDU may turn to the Greens to make up the difference, a result that would avoid a ‘grand coalition’ about which neither the CDU nor the SPD are enthusiastic. It’s called a ‘Jamaica’ coalition because the three colors of the Jamaican flag match the three colors typically associated with the three parties: black (CDU), yellow (FDP) and green. It would be an appealing coalition for Merkel, especially, because they could easily form an absolute majority based on current polls, and the CDU would remain the far largest party in government.

Even as recently as 2005, CDU/Green cooperation would have been an outlandish proposition in light of the cooperation between former chancellor Gerhard Schröder and the stridently leftist, anti-war Green leader Joschka Fischer. But there are signs that the Greens are moving to the center, with a voter base of relatively upper-class, middle-aged voters not unlike the CDU base, many of whom prefer Merkel over Steinbrück for chancellor.

Cem Özdemir, a son of Turkish immigrants, and one of two Green Party spokespersons alongside the more leftist Claudia Roth, and other rising party stars like Katrin Göring-Eckardt, are more politically centrist than the radical leftist generation that founded the Greens. Meanwhile, Merkel’s 2011 decision to phase out nuclear energy in favor of solar and wind power means that a potential CDU/Green government has already transcended what would have been a major sticking point in coalition negotiations.

The Greens are also incredibly pro-Europe, more so than many of Merkel’s own CDU and FDP allies, which means that a CDU/Green government would give Merkel a freer hand, in legislative terms, on setting European policy.

Though it’s never been tried in federal politics, a CDU/Green coalition governed in Saarland from 2009 to 2012, though that government ultimately fell apart, and the experiment hasn’t been repeated.

Likelihood: Toss-up. The conventional wisdom is that a CDU/Green coalition is less likely than another ‘grand coalition,’ but the truth is that neither Merkel nor the SPD wants another grand coalition, it’s surprisingly easy to see the Greens join a relatively moderate Merkel-led government, and CDU/Green collaboration would probably provide Merkel with the most stable potential coalition.

A return to ‘grand coalition’: CDU/SPD.

If the current CDU/FDP coalition falls short of a majority, everyone assumes that the next-likeliest coalition will be a return to a joint ‘grand coalition’ between Germany’s two largest parties. But there are reasons to suspect that a second grand coalition government within three election cycles will be much more difficult to negotiate than the previous one.

That’s because after the initial grand coalition, the CDU seemed to win all of the credit for the government’s success while the SPD was co-opted through its cooperation with its longtime conservative rivals. That dynamic plagued the 2009 campaign of SPD chancellor candidate Frank-Walter Steinmeier, who served as foreign minister in the prior grand coalition, and it continues to hamper Steinbrück, who as finance minister was responsible for the grand coalition’s economic policy, and who has had a difficult time drawing sharp contrasts to Merkel’s current policies on the economy and on European affairs.

That means that the SPD might prefer to stay in the opposition rather than join another grand coalition, and Steinbrück has even said as much — the SPD has no inclination to become Merkel’s lackeys again. While the SPD’s leaders have blustered that they will refuse to consider another Merkel-led coalition, the SPD will not have so much leverage that it could force Merkel out.

Even if it could, would the SPD prefer Wolfgang Schäuble, former chancellor Helmut Kohl’s one-time protégé and currently finance minister, who’s arguably even more hardline than Merkel? Would it prefer former longtime Bavarian CSU leader Edmund Stoiber or current Bavarian minister-president Horst Seehofer, who’s more eurosceptic than Merkel or Schäuble? Would it prefer to raise the profile of top Merkel lieutenant and potential successor Thomas de Maizière, currently Germany’s defense minister? Far more worrisome for Merkel is the strong possibility that the government would probably not last for four years, and that the SPD would spend much of its time engineering favorable early elections.

Nonetheless, the arrangement is already quite popular at the state level — five out of 16 state governments are CDU/SPD grand coalitions (including Berlin’s), and of the six CDU minister-presidents, three govern at the head of grand coalitions.

Likelihood: Toss-up — if the CDU and the FDP can’t form a majority, this remains the likeliest fallback option, but it’s by no means an automatic fallback, and Merkel might stand a real chance of being forced out as chancellor before the end of a full four-year term.

A red-green coalition: SPD/Greens.

Although the Greens are likely to im prove on their 2009 election result (10.7%), it will not be by enough to offset the depths of the SPD’s anticipated loss. But if Steinbrück and the SPD somehow manage an improbably comeback, the Greens will be crucial to forming a government, just as they were for the Schröder governments between 1998 and 2005, which featured Fischer as vice-chancellor and foreign minister.

prove on their 2009 election result (10.7%), it will not be by enough to offset the depths of the SPD’s anticipated loss. But if Steinbrück and the SPD somehow manage an improbably comeback, the Greens will be crucial to forming a government, just as they were for the Schröder governments between 1998 and 2005, which featured Fischer as vice-chancellor and foreign minister.

The red-green coalition remains the most common configuration at the state government level — six state governments currently feature SPD/Green collaboration (in the southwestern state of Baden-Württemberg, it’s more of a ‘green-red’ coalition, given that the Greens polled more than the SPD in the March 2011 state election and local Green leader Winfried Kretschmann currently serves as the minister-president).

However unlikely, the idea of a so-called ‘traffic light’ coalition that includes the SPD, the FDP and the Greens is even more farfetched. That’s because the FDP’s support is likely to be so weak that it won’t add much to any potential three-way coalition (it would likely be the smallest party in either a ‘traffic light’ or a ‘Jamaica’ coalition). Although the FDP once propped up the SPD governments of Willy Brandt and Helmut Schmidt in the 1960s and 1970s, there’s more ideological difference between the FDP and the SPD these days, to say nothing of the FDP’s proximity to Merkel. It would be challenging to move directly from supporting Merkel to supporting what would be an incredibly weak Steinbrück government. At the state level, there have been two ‘traffic light coalitions,’ but both of those lasted for just one government in the early 1990s.

Likelihood: Very low, unless Steinbrück and the SPD stage a late rally and reverse static polling trends over the past 12 months.

A broad leftist coalition: SPD/Green/Left.

Although the Left Party is likely to win less support than the 11.9% it polled in the previous 2009 election, it is polling well above the 5% threshold, and it will compete to win in much of what used to be East Germany. In 2009, it won more votes than any other party in the eastern states of Saxony-Anhalt and Brandenburg, and it could easily win a handful of eastern states this time around.

For the SPD, the idea of a broad leftist coalition with and the Left Party has been anathema for two reasons.

The first is that the core of the Left Party in the 1990s and early 2000s was a rechristened remnant of the old Soviet-era Socialist Unity Party that governed East Germany under Walter Ulbricht and Erich Honecker. To SPD leaders, that meant working with a dangerously backward-looking party with its roots in socialist authoritarianism. As time passes, however (the Berlin Wall was up for 28 years, but it’s now been 24 years since the Wall fell), those concerns are fading.

The second reason is that the current iteration of the Left Party is a merger between the old eastern socialists and a breakaway segment of western SPD renegades led by Schröder’s first finance minister Oskar Lafontaine. After leaving the finance ministry in 1999 after a stormy tenure, Lafontaine pulled increasingly further from Schröder and left the SPD altogether by 2005. The personality-based feud between the two former SPD allies made any collaboration between the SPD and the Left Party virtually impossible.

That’s slowly changing, and an SPD/Left ‘red-red’ coalition currently governs the state of Brandenburg. Gregor Gysi, the current parliamentary leader of the Left Party, recently came out strongly in favor of a broad leftist alliance during the current election campaign to oppose Merkel. Polls show that together, a hypothetical SPD/Green/Left coalition is competitive with the CDU/CSU/FDP coalition, even in an election that otherwise looks like it will be disastrous for the SPD. And if the SPD, Greens and the Left Party have together enough seats to form a majority, and if negotiations for either a CDU/SPD grand coalition or a CDU-Green coalition stall, it’s not out of the question this cycle. But a long-run rapprochement between the SPD and the Left Party will likely wait until the next election cycle under a new generation of SPD leadership.

Likelihood: Extremely low, though the SPD and the Left Party will have to come to terms with the possibility that a broad, reunited left is the fastest way for Germany to have a left-leaning government anytime soon.

4 thoughts on “Assessing the potential coalitions that might emerge after Germany’s federal elections”