Polling is an inexact science in Iran, so most polls should be taken with a healthy dose of skepticism. ![]()

But the field poll data coming from the U.S.-based Information and Public Opinion Solutions is more reliable than most, even though it’s not based in Tehran, because it conducts daily telephone interviews with a sample of over 1,000 potential voters within Iran.

The bottom line is that a runoff seems increasingly likely and, although that runoff seems likeliest to be a faceoff between conservative Tehran mayor Mohammad Baqer Qalibaf and moderate Hassan Rowhani, that’s by no means a certainty. I continue to believe that any of the five leading candidates could ultimately wind up in the runoff, especially if former longtime foreign minister Ali Akbar Velayati withdraws from the race in the next 48 hours in favor of Iran’s top nuclear negotiator Saeed Jalili, which remains a possibility, given that both candidates are viewed has having the closest ties to Ali Khamenei, Iran’s Supreme Leader since 1989. That’s especially true if you believe that the 2009 presidential vote was subject to massive electoral fraud — in such case, it seems possible that Rowhani could be excluded through chicanery. But despite the fact that he’s the most reformist of the six remaining candidate, Rowhani is the only cleric in the race, he has a solid relationship with Khamenei.

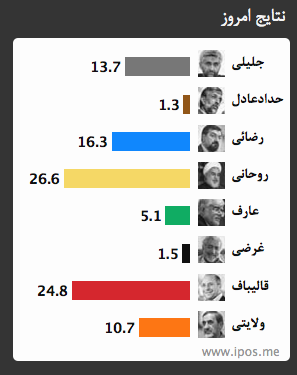

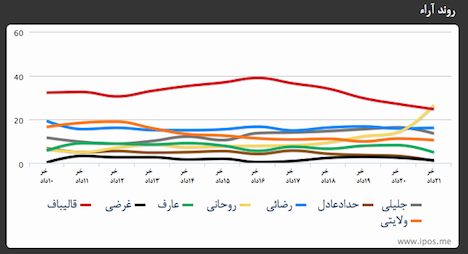

The latest results show Rowhani moving for the first time into the lead with 26.6% of the vote at the same time that former presidents Hashemi Rafsanjani and Mohammed Khatami have endorsed him. Rafsanjani, a political moderate, had registered to run for president in the election, but he was disqualified by the Guardian Council, a 12-member body close to the Supreme Leader that certifies candidates to run for office in Iran. The reformist Khatami, who had supported Rafsanjani’s presidential bid, indicated his support for Rowhani after his former vice president Mohammad Reza Aref dropped out of the race on Monday in favor of Rowhani. Rowhani’s support has steadily increased from a poll last week that showed him with just 8.1%. (Online polls have shown Rowhani and Aref with much wider support, but those seem skewed toward wealthier, more urban voters likelier to support more liberal candidates like Rowhani and Aref).

For the first time in an IPOS poll, the more ‘principlist’ conservative mayor of Tehran, Mohammad Baqer Qalibaf, has slipped into second place. Despite Qalibaf’s position as a conservative, he’s been a relatively popular mayor and is expected to do well among voters in Tehran, which is home to over 12 million of Iran’s 75 million people. Last week, however, Qalibaf held a much wider lead with 39% of the vote, though his lead seems to be shrinking as more undecided voters (57% of all voters last week) ultimately choose a candidate to support:

The third-place candidate, according to the poll, is Mohsen Rezai, whose support seems to be incredibly stable — 16.3% today and 16.6% last week. Rezai, the former head of the Revolutionary Guards, is seen as a more independent-minded conservative, and he pulls much of his strength from rural Iran and from within Iran’s military forces. Continue reading Rowhani, Qalibaf appear to lead polls to top Friday’s vote, advance to June 21 runoff