CARACAS, Venezuela — Imagine that following former prime minister Margaret Thatcher’s death last week, the United Kingdom implemented a week-long period banning the sale of alcohol.![]()

Or that in the weekend leading up to the 2012 U.S. presidential election, Americans would be unable to find a drink, forcing Americans to become public teetotalers.

But Friday night at 6 p.m., that’s exactly what happened in Venezuela in advance of the presidential election on Sunday — the ley seca takes effect, which means that no alcohol can be sold publicly in the country, through at least next Monday. It’s the third time in five weeks that the ley seca has been in effect — thirsty Venezuelans were out of luck for a week following the death of former president Hugo Chávez, and they were out of luck again during semana santa, the Holy Week.

In Venezuela, though, it’s just another obstacle to be overcome. In a country where the official exchange rate between dollars and bolívares and the black market rate can be up to 400% different, there will certainly be a way around

So around 6 p.m. tonight, if you were grabbing beers at a corner bar, for instance, your bartender might have switched out your bottle of beer into a more discrete, opaque cup. Venezuelans, especially, have practice getting around laws where economic incentives make breaking the law more efficient than upholding it. Prohibition in the United States in the 1920s, and really, the ‘war on drugs’ in the past 40 years in Latin America and the United States are illustrative.

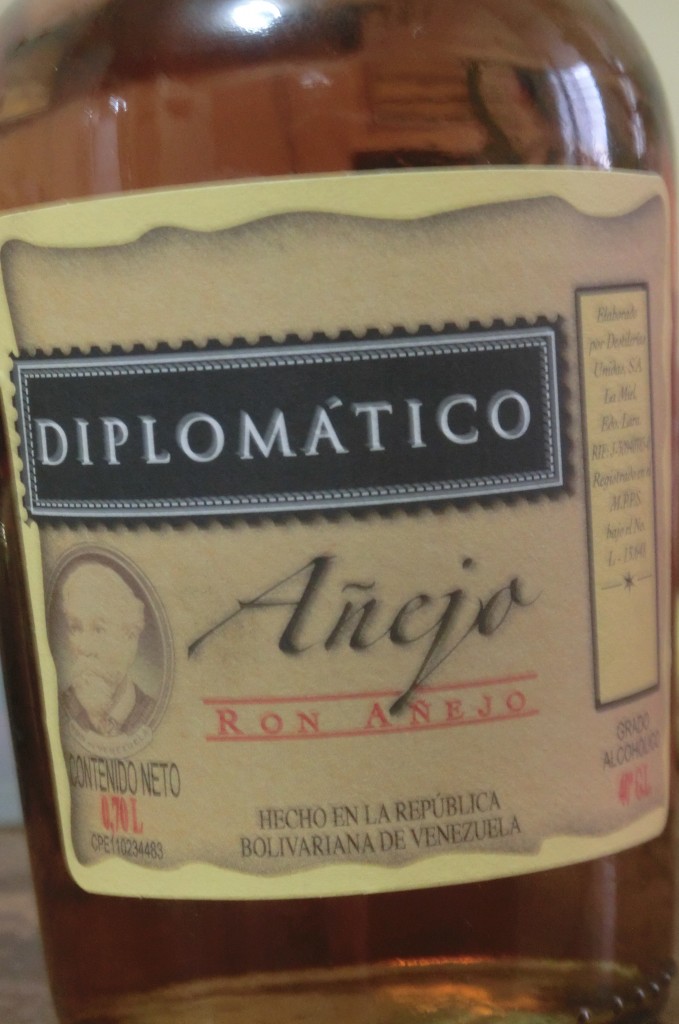

Though in a country of perfectly fine aged dark rum, Venezuela is one of the world’s top whisky importers and imbibers, I withhold any judgment as to Venezuelan taste.

So bottoms up — and happy election weekend!

Photo credit to Kevin Lees — Caracas, Venezuela, April 2013.