Polling in advance of tomorrow’s elections has been fairly steady for a month now in respect of the composition of the next Knesset (הכנסת), Israel’s unicameral parliament.![]()

Expectations, from day one of the campaign, have been nearly unanimous that prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu will remain as prime minister, but we still don’t know what the ultimate government will look like because there are so many options for Netanyahu in crafting a coalition.

So what options will Netanyahu have when he wakes up on January 23?

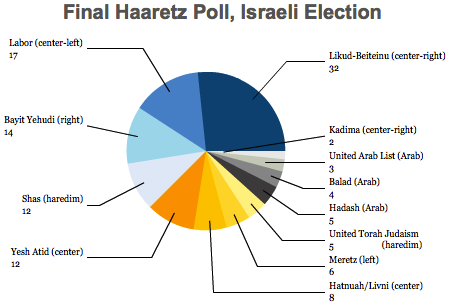

Let’s start with the final poll from Haaretz, Israel’s oldest newspaper, printed on Friday, which is relatively consistent with most polling in the final two weeks of the campaign:

‘Likud Beiteinu’ — the merger of Netanyahu’s Likud (הַלִּכּוּד, ‘The Consolidation’) and the more nationalist Yisrael Beiteinu (ישראל ביתנו, ‘Israel is Our Home’) of former foreign minister Avigdor Lieberman — is expected to win the largest bloc of seats by far. The proliferation of other right-wing parties and the remaining fragmentation among various center-left, leftist, ultraorthodox haredim, and Israeli Arab parties means that there’s virtually no way that any party other than Netanyahu’s bloc can form a viable governing coalition.

As in the last Knesset, it is expected that the two major ultraorthodox parties, Shas (ש״ס) and United Torah Judaism (יהדות התורה המאוחדת), will join the Netanyahu coalition, giving him about 15 more seats for a total baseline of around 50 seats, according to current projections.

Kadima (קדימה, ‘Forward’) seems assured to fall from the largest single party in the current Knesset (28 seats to just 27 for Likud) to merely two seats, if that. There are certainly many reasons for Kadima’s implosion — its years in the opposition wilderness, the refusal of former prime minister Ehud Olmert to run for office, the uncertain leadership of Shaul Mofaz (who joined, and then left, Netanyahu’s prior coalition), and the proliferation of no less than five center-left parties vying for the same pool of centrist voters.

If Kadima does win just two seats, though (and it may not win the 2% share of votes that represents the current threshold for representation in the Knesset), those two seats will go to Mofaz and Yisrael Hasson. Mofaz, a former defense minister in Ariel Sharon’s government a decade ago, has a Likud background; Hasson left Yisrael Beiteinu only in 2008 to join Kadima. So both likely MKs hail from Kadima’s right wing, and it seems likelier than not that they too would join Netanyahu’s coalition.

So that brings the baseline a little higher, perhaps even into the 50s. Given that there are 120 members of the Knesset, this requires Netanyahu to find anywhere from around seven to 12 additional seats in order to form a bare majority (although for many reasons, he may well want a wider coalition).

The three Israeli Arab parties (Hadash, Balad and United Arab List Ta’al) are projected to win a total of 12 seats, but are certain not to join any Netanyahu-led coalition, nor would the Zionist leftist party Meretz (מרצ, ‘Energy’), which is projected to increase its representation from three seats to six.

So that leaves us with a relatively narrow handful of coalition options.

Here are the five likeliest:

Right-wing coalition: Likud-Beiteinu + haredim + Kadima + Bayit Yehudi • ~65 seats

If you look at the ideology of the parties in this election, this is the most natural coalition. Bayit Yehudi (הבית היהודי, ‘The Jewish Home’), with just three seats, was already a member of the Netanyahu coalition in the prior Knesset.

They are expected to win around 14 seats in Tuesday’s election, and the incoming group of MKs from Likud and Yisrael Beiteinu are much more conservative than the existing caucus. That means there will be even more pressure from Netanyahu’s own base to form a broad coalition of the Zionist right. Bayit Yehudi is even more pro-settler than Likud and officially opposes the two-state solution (Netanyahu’s position is less than crystal clear, though he came out in favor of a two-state solution, under certain conditions, in 2009).

But the group’s leader since November 2012, Naftali Bennett, once served as Netanyahu’s chief of staff, from 2006 to 2008, and is though to have left on poor terms with Netanyahu, so the dynamics of any Netanyahu-Bennett relationship are uncertain.

Furthermore, at a time when Israel’s government is already facing significant international pressure over Palestinian negotiations, the Iran nuclear question, recent military engagement in the Gaza Strip and increasingly belligerent support of settlements in the West Bank, such a coalition will likely to meet a fair amount of disapproval from the international community, especially the United States, where president Barack Obama’s relationship with Netanyahu remains as strained as ever.

So with a purely domestic lens, this coalition makes the most sense, but it makes less sense if Netanyahu cares about his international reputation. If Netanyahu proceeds with a purely right-wing coalition, it will tell us a lot about how he sees the world.

Centrist coalition without Labor: Likud-Beiteinu + haredim + Kadima + Yesh Atid and/or Hatnuah • ~63 to 71 seats

If Netanyahu looks to the center, he’ll have to look to one of three parties.

Labor (מפלגת העבודה הישראלית), is expected to win the most seats of any of the center-left parties, but its leader Shelly Yacimovich would likely demand a senior ministerial post and, above all, concessions from Netanyahu for a more activist economic policy, with a greater focus on public spending for health care, education and housing than with cutting Israel’s growing budget deficit (over 4% in 2012 and climbing). For what it’s worth (probably not much at this point), Yacimovich has ruled out joining any Netanyahu coalition.

Hatnuah (התנועה, ‘The Movement’), the party of former foreign minister and former Kadima leader Tzipi Livni, is expected to win just eight seats, so Hatnuah’s support alone may not even be enough to form a stable coalition. Although Livni’s more open to joining a Netanyahu coalition, she would likely demand a more dovish approach from Netanyahu with respect to the Palestinian negotiations, as well as the foreign minister post, something Netanyahu is unlikely to relinquish.

Political newcomer Yair Lapid and his new centrist party Yesh Atid (יש עתיד, ‘There is a Future’) is projected to win almost as many seats as Bayit Yehudi — a few less than Labor, but more than Livni’s party. Lapid himself seems to covet the education portfolio — a smaller portfolio than either Yacimovich or Livni would demand, and probably an open one if current education minister Gideon Sa’ar is elevated, as expected, to finance minister. Yesh Atid has also billed itself as a ‘center-center’ party, meaning that it will be more amenable to the budget cuts that Netanyahu will likely want to make to recalibrate Israel’s public finances.

That doesn’t mean there won’t be problems — Lapid has been outspoken in his desire to end exemptions from service in the Israeli Defense Forces for Israel’s haredim, which could cause some tension with Shas and United Torah Judaism.

Nonetheless, if Netanyahu forms a more centrist coalition, and current projections hold up, Yesh Atid seems by far the likeliest choice, both because Netanyahu gets the most seats in exchange for the least number of policy and ministerial concessions, and because it gives Lapid a platform for his own political future — perhaps as heir to Netanyahu as a future center-right prime minister.

Centrist coalition with Labor: Likud-Beiteinu + haredim + Kadima + Labor • ~68 seats

Although Yacimovich has ruled out a coalition with Netanyahu, such promises are often broken by Israeli politicians in an increasingly fluid political landscape.

On the one hand, Yacimovich seems poised to become the undisputed opposition leader to Netanyahu. She will have the length of the next Knesset to burnish her image as not only the politician with the most ambitious economic policy platform in Israel and Netanyahu’s chief foil, but also to enhance her credentials on security, in order to make a more serious run at prime minister by 2017.

On the other hand, joining the Netanyahu coalition might be the easiest path for Yacimovich to develop credibility with Israeli voters on the Palestinian and security issue, even at the risk of ting herself to what may be an unpopular government heading into the next elections.

Furthermore, if neither Hatnuah nor Yesh Atid can win enough seats to form a stable coalition for Netanyahu, it is difficult to believe that Labor’s MKs would refuse to join a coalition when the alternative is letting Bayit Yehudi into government.

Right-wing coalition (with centrist fig-leaf participation): Likud-Beiteinu + haredim + Kadima + Bayit Yehudi + Yesh Atid and/or Hatnuah • ~73 to 85 seats

If Netanyahu ultimately decides that he wants Bayit Yehudi in his coalition (either because his Likudnik base demands it or because he believes Bennett is less dangerous within government than outside it), he may still want to find at least one centrist party to join the coalition to ameliorate international concerns that the Israeli government has become even more conservative.

That means that bringing either Yesh Atid or Hatnuah into government. In this scenario, it seems likely that either the foreign or defense post would have to go to either Lapid or Livni — especially in a world where Ehud Barak doesn’t return as defense minister.

Grand coalition: Likud-Beiteinu + haredim + Kadima + Bayit Yehudi + Labor + Yesh Atid and/or Hatnuah • ~82 to 102 seats

This option is really just a stronger version of the previous coalition. To the extent that Netanyahu has the widest possible coalition, he not only has more room to maneuver, but Bayit Yehudi’s influence (and Bennett’s) would be diluted by a stronger center-left presence. Taken to its extreme, it leaves Meretz as the largest opposition to the government — which is to say, not much of an opposition at all.

In order to effect such a coalition, Netanyahu would likely have to provide extensive concessions on economic policy to Labor, give the foreign or defense ministry to Livni, plus sweeteners for Yesh Atid. It may well be that Bennett would also require more concessions in order to join such a broad-based coalition.

Although it seems unlikely today, it will remain a tantalizing possibility throughout the next Knesset, and you could see how any number of foreign policy crises could quickly provide the political incentives for a broad ‘grand coalition.’

Final note: why not a broad center-left coalition?

Taken together, Labor, Kadima, Yesh Atid, Hatnuah, Meretz and the Arab parties are projected to win only 57 seats in the Knesset, four short of an absolute majority. Even if the center-left parties somehow outperform projections to win enough seats to cobble together the narrowest of majorities, it would require a feat of cooperation that’s so far been unthinkable in Israeli politics.

Not only would all five center-left parties have to agree to a platform for government and on one candidate for prime minister, they would all have to reject what would surely be tempting offers to join Netanyahu. In addition, each of the three Arab parties would have to be invited into government (or at least to prop up the government), and it’s unclear that any of the center-left parties — let alone all five of them — would be willing to assume the political risk of forming a government that depends on Arabs.

4 thoughts on “A guide to the five likeliest Netanyahu-led governing coalitions for Israel”