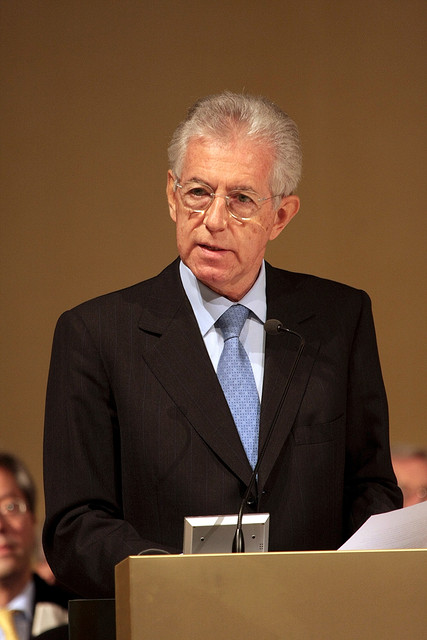

One of the enduring questions of the Italian election has been whether outgoing prime minister Mario Monti will run or not.![]()

Given the popularity of his reforms with the European Union leadership generally and with international investors, his return as prime minister after the February elections is by far their top preference. Any indication that Italy will make a U-turn on its recent reforms could send Italian bond rates skyrocketing back to the 7%-and-climbing levels of November 2011.

Presumably, too, Monti would very much like to return for a longer term as prime minister to see through further reforms, further budget cuts, and be remembered as the ‘grown-up’ prime minister that put Italy on a long-term path for future growth.

But it’s an important question not just for Italy, but for all of Europe, and the U.S. economy as well.

Legally, of course, Monti cannot run for office in his own right because he’s a senator for life’ and thus, is unable run for a seat in Italy’s lower parliamentary house, the Camera dei Deputati (House of Deputies) — but that’s not really an answer as to whether he’s ‘running’ or not.

Over the weekend, Monti sort-of emerged as a candidate for the elections — he said he is ‘willing’ to lead a coalition of small centrist parties, each of which would vote to install Monti as prime minister for a second Monti-led government. He had harsh words for Silvio Berlusconi, who has returned, despite his massive unpopularity, to lead the conservative Popolo della Libertà (PdL, People of Freedom) by asserting over the weekend that Berlusconi has demonstrated a ‘certain volatility in judgment’ — an incredibly muted criticism, perhaps, but a criticism nonetheless. He continued his aggressive tone today with respect to Pier Luigi Bersani, who leads a center-left coalition that features the Partito Democratico (PD, Democratic Party), by urging Bersani to silence the extremists within his own alliance.

It’s an incredibly difficult tightrope walk for Monti, given that the polls show his coalition is set to finish no better than fourth, so the only way he can return as prime minister is through the election of a hung parliament.

Monti must at least provide a pro forma argument for supporting the ‘pro-Monti’ coalition, or he would risk minimizing the number of votes that will go to the ‘Monti coalition’ — without at least some floor of campaign activity from the incumbent prime minister himself, votes will inevitably slip away from the center to the two main center-right and center-left blocs, leading to what polls show would be a clear win for Bersani, not a hung parliament.

If Monti campaigns too hard, however, he risks diminishing his above-the-fray ‘technocratic’ mien. He’s already done that now, to some degree, by directly engaging his political rivals. But more fundamentally, if Monti campaigns too hard and voters are seen to have directly rejected Monti, he will have diminished not only his own political capital, but the cause of political reform that’s been his government’s chief aim. His political rivals will feel even less pressure to continue Italy’s reformist path. Bersani’s center-left coalition leads polls with around 35% of the vote to no more than around 20% for Berlusconi’s center-right coalition and around 15% for populist comic and blogger Beppe Grillo’s anti-austerity Movimento 5 Stelle (M5S, the Five Star Movement). The autonomist Lega Nord (Northern League) has supported Berlusconi in the past as a sometimes-difficult ally, and it hasn’t yet indicated whether it will ally with Berlusconi in the elections this year, though it wins around 4% to 6% by itself — not enough for Berlusconi to have a realistic chance of returning to government.

The problem for Monti is that the groups that comprise the ‘Monti coalition’ poll at barely 10% to 12%.

The three main parties include:

- The Unione di Centro (UdC, Union of the Centre), a small centrist party comprised of former Christian Democrats and led by Pier Ferdinando Casini — they’ve provided support to Berlusconi-led coalitions in the past and have indicated they could form a governing coalition with Bersani as well, despite a preference for Monti. They retain considerable strength in southern Italy and, in particular, in Sicily. Casini is seen as very close to the Vatican, however, and the UdC could not be expected to support socially liberal laws (e.g. gay marriage).

- Futuro e Libertà per l’Italia (FLI, Future and Freedom), the party of Gianfranco Fini, once the leader of the now-defunct National Alliance. Fini moved gradually over his career from the neofascist right toward the center, and he became one of the most important center-right leaders in the 2000s. Although he served as deputy prime minister, foreign minister and as president of the Camera dei Deputati in the 2000s, he split with Berlusconi increasingly after the 2006 election.

- Verso la Terza Repubblica (VTR, Toward the Third Republic), a centrist group formed in late 2012 solely for the purpose of championing a new Monti government, founded by Luca Cordero di Montezemolo, Ferrari CEO, former Fiat CEO and former president of Confindustria (Italy’s employer’s federation).

It was inevitable that Monti’s popularity would fall under the weight of a new recession and budget cuts. But he’s still more broadly popular than a Vatican shill, Ferarri’s CEO and a former fascist who carried Berlusconi’s water for nearly a decade.

In just over a year of government, Monti pushed through various reforms to stem tax evasion and to open more professions in Italy to labor market competition by, for example, making it easier to terminate employees. He also raised the pension age for women to 62 and for men to 66 and implemented both tax hikes and spending cuts in order to cut Italy’s budget — Italy’s public debt, around 120% of GDP, contributes high costs in interest and debt service for Italy’s government. I’ve long thought the structural reforms have been more important than the budget austerity, given that since the 2000s, Italian governments have generally been more fiscally responsible. Nonetheless, the reforms of Monti’s first government are really just a down payment on further reforms, which I believe are the real key to boosting GDP growth in Italy (well, and reversing Italy’s population decline).

Even if his gambit doesn’t work, and Monti doesn’t become prime minister again, he is hoping he can still maximize his influence on a Bersani-led government that, for better or worse, would have to continue pursuing at least many of Monti’s reforms (in the same way the pro-growth François Hollande has continued to pursue budget cuts and tax hikes in France). Bersani knows that Monti’s stamp of approval will go a long way to keeping the international wolves at bay, and appointing Monti as his finance minister — or as the largely ceremonial, if influential, president — would send the right signals to them.

One thought on “Italian prime minister Mario Monti has a ‘Goldilocks’ problem”