Lurking behind the sexier issues at the forefront of tomorrow’s Québec provincial elections — sovereignty, federal-Québec relations, health care, corruption inquiries, tuition fees and student protests — lies an issue that will be quite strongly affected by who wins.

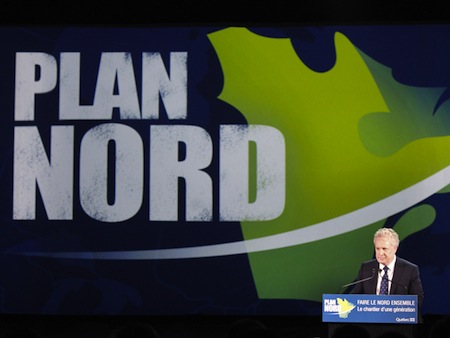

That issue is premier Jean Charest’s Plan nord — a plan announced in May 2011 to exploit the natural resources in the great expanse that comprises the northern two-thirds of Québec. The idea is that over the next 25 years, the Plan will attract up to $80 billion in investments for mining, renewable and other forms of energy and forestry. Charest, whose Parti libéral du Québec (Liberal Party, or PLQ) is struggling to win a fourth consecutive mandate, has made it one of his government’s top priorities, although it’s been met with some resistance from environmentalists as well as from the native Innu people, around 15,000 of whom inhabit Québec’s far north, to say nothing of Charest’s political opponents.

His government claims that northern Québec contains deposits of nickel, cobalt, platinum group metals, zinc, iron ore, diamonds, ilmenite, gold, lithium, vanadium and rare-earth metals, and that, with a warming climate and melting polar ice, extracting the mineral wealth will be easier than in past generations. The region, although fairly undeveloped and remote, already produces 75% of hydroelectric power in Québec.

Pauline Marois, who leads the sovereigntist — and more leftist —

Parti québécois (PQ), which leads polls for tomorrow’s election, has said that

she will not scrap the plan if elected, but will instead raise royalties on mining companies from 16% to 30% for mining companies that achieve a certain level of profits, with a minimum royalty of 5% on all mining companies. Charest’s government has already raised royalties from 12% to 16%.

François Legault, the leader of the newly-formed Coalition avenir Québec (CAQ), has argued that Charest’s government is “putting all its eggs in one basket” with Plan nord, but he hasn’t said he wants to scrap it — he’s criticized Marois as well for trying to extract more royalties from mining companies. Legault has proposed using $5 billion from the province’s $160 billion Caisse de depot et placement (its public pension fund) to capitalize a new natural resources fund.

In announcing Plan nord, Charest stressed the developmental elements of the plan, which would include a $2.1 billion investment from the province in northern infrastructure and which would also aim to build roads to link communities — in many cases, for the first time.

He also stressed the conservation elements of the plan — the government has claimed it will set aside 50% of the region for natural protection and unavailable for industrial development.

Late last week, however, Charest’s PLQ was ranked the worst of the three parties for the environment in a survey among environmental groups — a fourth party, the leftist and sovereigntist Québec solidaire, scored the highest with 83% under the survey, while the Liberals scored just 33%. The report followed another news story in Le Devoir late last week that claimed the Plan nord would wipe out wild caribou herds in the region.

Meanwhile, it is not clear that Charest has ever had the native population, which owns much of the land and mineral rights, quite on board. Also last week, Ghislain Picard, Grand Chief of the Assembly of First Nations of Quebec and Labrador, criticized the Charest government in a criticized the manner in which the Charest government has approached northern development: Continue reading Plan Nord and the Québec election →

![]()

![]()