Dutch prime minister Mark Rutte looked more likely than not to continue as prime minister of the Netherlands Tuesday night after his party, the free-market liberal Volkspartij voor Vrijheid en Democratie (VVD, the People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy) won the largest share of the vote in the Dutch election, with 98% of the votes counted.

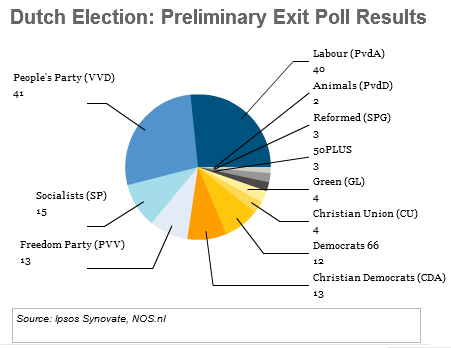

The VVD won 26.6% of the vote, entitling it to 41 seats in the Tweede Kamer, the lower house of the Dutch parliament, an increase of 10 seats over the 2010 election.

It was followed very closely by the social democratic Partij van de Arbeid (PvdA, Labour Party), with 24.8%, which entitles it to 39 seats, a nine-seat increase from 2010 under the incredibly strong performance of Labour leader Diederik Samsom, a former Greenpeace activist who took over the party’s leadership only in March 2012 and spent much of the past year trailing the more staunchly leftist Socialistische Partij (SP, the Socialist Party) of Emile Roemer.

All things being equal, Rutte and Samsom are the clear winners of the election. Rutte will now be able to attempt to form a government with a credible mandate for bringing the Dutch budget within 3% of Dutch GDP — his prior government fell in April of this year when Geert Wilders, the leader of the Partij voor de Vrijheid (PVV, the Party for Freedom), refused to support further budget cuts.

Samsom is nearly as much a winner as Rutte, though. His polished performance in the various Dutch leaders debates (in contrast to Roemer’s often bumbling performances) convinced Dutch voters that he possesses sufficient poise to be prime minister. Samsom, a more leftist leader of the Labour Party as compared to his predecessor, former Amsterdam mayor Job Cohen, offered essentially the same anti-austerity option as Roemer, but without the anti-Europe sentiment of a Roemer-led government. Even if he remains in the opposition, he can become the chief voice against Rutte’s budget cuts during the next government and work to build upon his party’s gains from today’s election.

The Socialists finished far behind with 9.7% and 15 seats — unchanged from 2010, but a huge disappointment after polls showed a gain of potentially 35 seats just a few weeks ago.

The Socialists, in fact, finished just behind Wilders’s anti-immigration, anti-Europe PVV — with 10.1% and also just 15 seats, it’s a nine-seat drop from the 2010 election, a huge disappointment for Wilders and a success for those who favor an approach of integrating Muslims into Dutch culture rather than excluding them. Essentially, voters seemed to blame Wilders for dragging them back to the polls just two years after the last election — and furthermore, the essentially pro-European Dutch did not seem to take to Wilders’s contrived and virulent campaign to bring the Dutch guilder back and pull the Netherlands out of the eurozone. Wilders never found the same resonance over Europe in 2012 that he obvious found over Muslim immigration in 2010.

Rutte’s coalition partners, the once-dominant but now-atrophied Christen-Democratisch Appèl (CDA, Christian Democratic Appeal) won just 8.5% and 13 seats, a drop of eight seats from 2010. The progressive / centrist Democraten 66 (Democrats 66) won 7.9% and 12 seats.

Also returning to the Tweede Kamer were the center-left, Christian Democratic ChristenUnie (CU, Christian Union) with 3.1% and five seats, the ecologist GroenLinks (GL, GreenLeft) with 2.3% and three seats, the Calvinist, ‘testimonial’ Staatkundig Gereformeerde Partij (SGP, the Reformed Political Party) with 2.1% and three seats, and finally, both of the newly-formed Labour spinoff 50PLUS and the animal welfare advocate Partij voor de Dieren (PvdD, Party for the Animals), each with 1.9% and two seats.

As soon as tomorrow, cabinet formation talks are expected to begin — and for the first time, the Dutch parliament will take the lead in exploring potential coalitions (instead of the Dutch monarch, Queen Beatrix). Those talks typically take up to three months, but can take longer — the 2010 government was formed after four months of negotiations.

Given the result, it looks like three coalitions are possible: Continue reading Rutte’s VVD edges out Samsom’s Labour as both gain in Dutch election →