Francisco ‘Kiko’ Vega de Lamadrid has emerged as the winner of Sunday’s gubernatorial election in the Mexican state of Baja California, giving the conservative Mexican opposition a major boost in a high-profile election a year after its crushing defeat in the July 2012 Mexican presidential election.

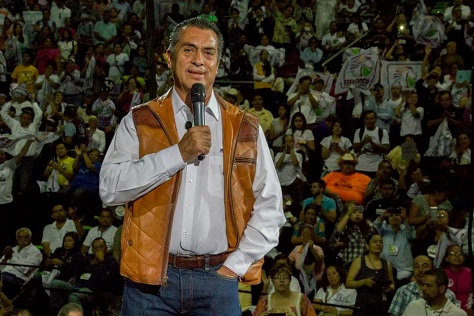

Vega (pictured above), a former Tijuana mayor, a Mexican congressman from 2009 to 2012, and a former finance secretary of Baja California in the late 1990s, led an electoral coalition dominated by the conservative Partido Acción Nacional (PAN, National Action Party). Initial results showed Vega having won around 47.15% of the vote to just 44.15% for Fernando Castro Trenti, the candidate of the governing Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI, Institutional Revolutionary Party).

That means not only that Vega will be the sixth consecutive PAN governor of Baja California, but that the PAN will continue to hold onto one of the party’s most symbolic strongholds a year after the PRI’s young and photogenic Enrique Peña Nieto won the Mexican presidency, giving the PAN a boost after a year of infighting and internal distractions. A PAN loss in Baja California would have been nothing short of a complete disaster for the party and for its current leader, Gustavo Madero.

The entire peninsula of Baja California is technically divided into two states — Baja California and Baja California Sur — and the state’s population of around 3.3 million means that it’s not among México’s largest states.

But there are a lot of reasons why Baja California is nonetheless an important state in Mexican politics.

One obvious reason is its proximity to the United States. The sprawling border cities of Mexicali and Tijuana have been focal points of migration of workers and products, both legal and illicit, from México to the United States, for decades at a time when U.S. policy is focused on immigration reform. Both the peninsula and the state are among the most popular tourist destinations for U.S. citizens drawn to Baja’s beachfront bounty — although foreigners can hold 50-year interests in Mexican property in trust, foreigners are still banned from owning beachfront property in Baja California under laws dating back to the Mexican Revolution, despite recent legislation to ease property restrictions.

But Baja California also plays an important role in the development of Mexican democracy — it was in Baja California that a Mexican opposition party first won a gubernatorial race after decades of PRI dominance in what had been México’s one-party state since the 1920s. When the PAN’s candidate, a young local businessman named Ernesto Ruffo Appel, won the July 1989 gubernatorial race, then-president Carlos Salinas acknowledged the PRI’s defeat on election night, thereby propelling the PAN to its first major shot at power in Mexican history.

It’s not difficult to draw a direct line from that night to ever greater milestones for Mexican democracy — the 1992 elections that saw the PAN win further gubernatorial victories; the 1997 elections that brought the leftist opposition Partido de la Revolución Democrática (PRD, Party of the Democratic Revolution) to power in the Distrito Federal, where the PRD has essentially governed México City ever since; and, of course, the 2000 presidential election that delivered the Mexican presidency to the PAN’s Vicente Fox.

Though Fox’s successor, Felipe Calderón, followed him to the presidency in 2006, the PAN’s 12-year hold on the Mexican presidency collapsed after Peña Nieto’s victory, which followed a decade-long project of rebranding the PRI’s role in a 21st century, multi-party democratic México. The PAN’s candidate, Josefina Vázquez Mota, finished far behind Peña Nieto with just 25% of the vote and weakened by internal disputes within the PAN, despite the historic nature of her candidacy — Vázquez Mota was the first female major-party candidate for the Mexican presidency.

Vega’s victory gives the PAN something to celebrate and an opportunity to pivot from the nadir of its 2012 effort and the ensuing internal squabbling that’s followed, which ultimately bodes well for balancing México’s various political forces in advance of over a dozen gubernatorial races in 2014 and midterm congressional elections in 2015.

The victory also boosts Peña Nieto’s national agenda, the so-called Pacto for México among all three parties in the Mexican Congress, where no party holds an absolute majority of seats — the PRI actually lost 30 seats in the lower house, the Cámara de Diputados, in last year’s simultaneous legislative elections. Peña Nieto is planning to push for tax and energy sector reform in coming months, and he’ll need the PAN’s support in order to carry out those reforms, especially given the Mexican left’s suspicion of any moves toward private investment in Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex), Mexico’s state-owned oil company.

That’s because the PAN’s victory will, for the time being, steady Madero’s leadership, who signed the Pacto with Peña Nieto earlier this year. Although Calderón himself pushed for tax reform last decade (it was blocked by the PRD and the PRI at the time) and both reforms are largely in line with the PAN’s free-market economic views, the Pacto has divided Mexico’s conservatives, who were already split between maderistas and calderonistas (today, corderistas) following the December 2012 election for the PAN’s presidency between Madero and Ernesto Cordero, a longtime Calderón loyalist and former Calderón finance minister.

In May, Madero demoted Cordero, who has been more skeptical about the Pacto, from his role as the PAN’s caucus leader in the Senato, the Mexican Congress’s upper house. Cordero, a longtime Calderón loyalist, has been more pessimistic about the Pacto than Madero or Santiago Creel, also a senator and formerly Fox’s interior minister. Both Cordero and Creel contested the PAN’s 2012 presidential primary against Vázquez Mota, and all three politicians plus Madero could seek the presidency in 2018.

Continue reading Why the PAN’s victory in Baja California is good news for Mexican democracy →

![]()

![]()