Vicente Fox wants you to know that Mexico is not paying for ‘that fucking wall.’![]()

![]()

Though US president Donald Trump officially took office just six days ago, his willingness to push his key campaign proposal of building a border wall along the southern border of the United States has already touched off a diplomatic crisis with Mexican officials. After Trump enacted an executive order (of somewhat dubious legality) instructing the federal government to start construction on the wall, Mexico’s president Enrique Peña Nieto cancelled a planned trip to meet Trump in Washington today.

Though Peña Nieto welcomed Trump on a surprise campaign visit to Mexico City last summer, backing down from confronting someone who was then just the Republican Party presidential nominee, Wednesday’s executive order and the White House’s insistence that Mexico will pay for the wall led Peña Nieto to push back in a video message late Wednesday night. Trump responded with his own Twitter rant on Thursday, essentially daring Peña Nieto to cancel the meeting, during which the two presidents planned to discuss cooperation on security and renegotiation of the North American Free Trade Agreement.

No one, however, has been more outspoken against Trump than Fox, who served as president between 2000 and 2006 and who has railed against Trump’s proposed border wall, routinely in profane terms. In September, Fox gleefully took a bat to a Trump-shaped piñata and, upon completion, noted that Trump was just was empty-brained as the empty piñata.

Fox is a former president who knows a little something about political revolutions.

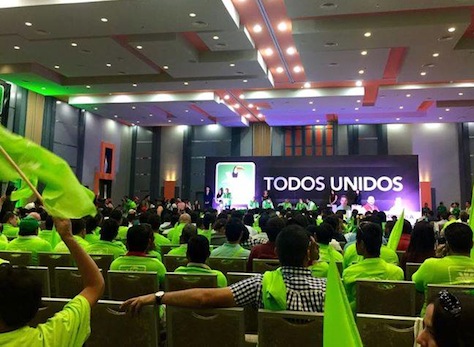

In 2000, he became the first president in seven decades from outside the long-governing Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI, Institutional Revolutionary Party). His election, to this day, represents a watershed moment in Mexico’s multiparty democracy. Fox (and his successor) are members of the conservative Partido Acción Nacional (PAN, National Action Party) that held the Mexican presidency for 12 years — until the telegenic Peña Nieto’s election in 2012, when the PRI returned to Los Pinos. Fox, like George W. Bush in the 1990s, was a governor, and before the Sept. 2001 terrorist attacks refocused the Bush administration’s efforts, the two presidents had hoped to work together on immigration reform and deeper harmonization between the two countries, a priority that fell to the back burner with two wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. Continue reading Mexico starts to fight back in earnest against Trump’s US border wall and protectionism threat