Even as Enrique Peña Nieto basks in a largely successful first year as president, capped off with a massive energy reform that will introduce elements of privatization and foreign investment to Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex), the state oil company, and the first step of tax reform that will raise VAT of junk food and sodas, Mexicans aren’t sure that his administration is making the same progress on security. ![]()

![]()

Nowhere is that more true than in Michoacán.

A sprawling Pacific state that unfurls from the western Mexican coast inland nearly to the capital of México City, Michoacán wasn’t necessarily predestined to become a synonym of drug-fueled anarchy. It’s not home to the Zapatista-style insurgency that former president Ernesto Zedillo faced in Chiapas in the mid-1990s, the destabilizing political protests that former president Vicente Fox faced in Oaxaca in 2006, or to the horrific body counts in Ciudad Juárez and elsewhere in Chihuahua that dominated gory headlines just a few years ago during the presidency of Felipe Calderón.

But even if Michoacán didn’t become the initial battleground in Mexico’s drug war, it’s now certainly the center of the most serious regional struggle that Peña Nieto faces just 14 months into his presidency, and it’s where Peña Nieto earlier this week announced he would invest $3.4 billion for development in the troubled state:

The funding will go to scholarships for students, pensions for the elderly and credits for small business owners, as well as for infrastructure projects such as highways and a new hospital.

The plan, Peña Nieto said, was meant “to recover security, establish conditions of social order and spur economic development.”

It’s a bold step that departs from Peña Nieto’s previous approach to security — and it could turn the tide in Michoacán.

Peña Nieto, the candidate of the Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI, Institutional Revolutionary Party), won a convincing victory in the July 2012 presidential election, bringing to an end 12 years of government dominated by the center-right Partido Acción Nacional (PAN, National Action Party). When Fox won the Mexican presidency in 2000, he brought to an end 71 years of consecutive PRI rule rooted in the Mexican Revolution of the 1910s.

In contrast to the Calderón administration’s approach, with its military-heavy focus on eliminating cartel ‘kingpins,’ Peña Nieto outlined a strategy to prosecute homicides, kidnappings and extortions through a surge of police force in the most violent parts of the country. Instead of targeting cartel leadership, which critics claim splinters cartels, thereby engendering more violence as newcomers fight to fill new voids, Peña Nieto instead hoped to crack down on drug-related violence more than the drug trade itself. It’s true that Peña Nieto’s approach shares in common some features of the previous PRI approach to drug policy, the basic deal being: the government would leave cartels to the drug business so long as cartels didn’t cause violence against innocent civilians. At the federal, state and municipal level, it was a deal often lubricated through massive corruption that helped keep the PRI in power.

Even today, it doesn’t help the PRI’s image that interior secretary Miguel Ángel Osorio Chong, who ostensibly leads the Mexican government’s fight against drug trafficking, was himself investigated for ties to Los Zetas and the drug trade during his stint as governor of Hidalgo state between 2005 and 2011.

Upon his inauguration, Peña Nieto recruited Óscar Naranjo, a former Colombian general with decades of experiences with Colombia’s own painful struggle against drug cartels, to guide and craft Mexican security policy, most notably by creating a 40,000-strong paramilitary gendarmerie. That plan was quickly downsized in the face of opposition, and earlier this week, Naranjo announced his return to Colombia, amid signs that Peña Nieto’s security policy has not worked so well. In August 2013, 49% of Mexicans reported in an El Universal poll that they felt less safe today under Peña Nieto than they did during the Calderón years.

And it’s Michoacán that has now become the symbol of the PRI’s failure to tackle México’s ongoing drug violence.

Though Michoacán’s story is a local story, it’s also a case study of how the Mexican drug war continues to wreak upon much of the country. The dominant drug cartel here is neither the Sinaloa cartel (shown in blue below) that controls the illicit trade throughout much of northwestern México nor Los Zetas (shown in red below), a group of soldiers-turned-cartel-protectors-turned-cartel-operators, which now control the drug trade throughout much of the eastern half of México and the Yucatán after vanquishing the Tamaulipas-based Gulf cartel.

To the contrary, La Familia Michoacana dominated the state’s drug trade historically. Though it formed in the 1980s ostensibly as a vigilante group to provide security and deliver aid to the poor, it quickly mutated into an organized crime outfit in alliance with the Gulf cartel. The group began to dominate the drug trade in Michoacán during the mid-2000s when Los Zetas started to usurp territory from the Gulf cartel. A rivalry developed between the two forces, and La Familia famously dumped the decapitated heads of six Zeta rivals on the floor of a dance club in Uruapan in September 2006. Shortly after Calderón — himself a native of Morelia, the capital of Michoacán — took office in December 2006, he deployed 6,500 Mexican troops to the state to attempt to pacify the drug-related violence in the state.

But that didn’t seem to break La Familia. The homegrown cartel sent a message to the state’s governor, Leonel Godoy, in 2008 when it tossed grenades into Morelia’s central plaza. In November 2010, Calderón’s government announced that secuirty forces killed La Familia‘s founding leader Nazario Moreno González in a two-day gun battle with Mexican police.

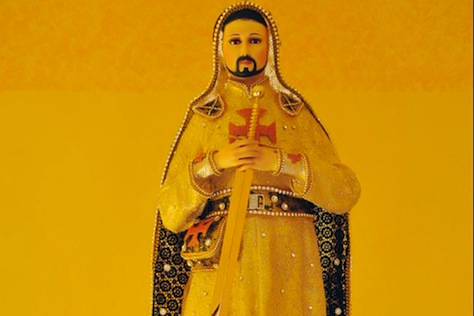

Like a hydra that regenerates even the most vital of its body parts, La Familia didn’t die so much as regenerate upon Moreno’s death into the Caballeros Templarios (Knights Templar), initially an offshoot of La Familia, which now effectively functions as its successor under the leadership of Servando Gómez, who formerly served alongside Moreno in the leadership of La Familia (and, if you can believe it, a one-time schoolteacher). Today, the drug cartel is responsible for providing much of the Mexican methamphetamine supply. But many Michoacán residents still believe Moreno is still alive, and some even worship ‘San Nazario’ today as a kind of local saint.

Over the course of 2012 and 2013, the Knights Templar wrested control of the entire state of Michoacán, with Mexican security forces unable to regain control of much of the state’s territory. The dominance of the Knights Templar extended not only to the drug trade or other criminal pursuits, but also to the state’s political and economic networks. In the November 2011 gubernatorial election, Fausto Vallejo, a member of Peña Nieto’s PRI, narrowly defeated Luisa María Calderón, the PAN candidate, and the sister of the Mexican president — a margin that both the PAN and the leftist Partido de la Revolución Democrática (PRD, Party of the Democratic Revolution) credit to interference from drug traffickers.

For instance, Jan-Albert Hootsen detailed last year in Vocativ how the cartel co-opted the local avocado industry:

The extortion usually occurs by phone. The narcos call farmers and tell them how much they have to pay: 10 cents for every kilogram of avocado they produce, $115 for every hectare of land they own. Those who export the fruit have to pay up to $250 per hectare. The Templarios collect the money—cash placed in a bag at an agreed upon drop off—once a year, usually in January. The extortion fees are non-negotiable, says one farmer, who asked to remain anonymous for fear of reprisals. “It’s no use trying to convince them to demand less,” he says. “They know exactly how much you own. If you lie to them, they’ll kill you or one of your family members.”…

Every link in the avocado production chain is a cash cow for the cartel, from the quadrilleros, or pickers (whose employment agencies are forced to pay $3.50 per worker per day), to those who buy, develop and sell plantations. The extortion racket is lucrative. In some municipalities, the estimated proceeds come to $3 million per year.

But early last year, a new force began organizing, the ‘autodefensas,’ self-defense forces that took it upon themselves to seize back control of Michoacán from the Knights Templar. Last month, a vigilante group (pictured above, top) nearly took control of Apatzingán, the stronghold of the Knights Templar within Michoacán, forcing the Mexican government to send armed forces and police to the city to bring order — they mostly pleaded with the vigilantes to disarm in the face of what would have been a bloody urban battle between the Knights Templar and the autodefensas. Ultimately, Peña Nieto hopes to merge the Michoacán autodefensas formally into the broader penumbra of Mexican security forces.

With greater cooperation between the autodefensas and the Mexican government, and with $3.4 billion in new development throughout the state, it’s not difficult to believe that Michoacán may be headed for more tranquil days in the future. A similar focus from the Calderón administration in Ciudad Juárez also reduced homicides in the crime-ridden border city that abuts El Paso, Texas.

But Peña Nieto’s government — and Latin America, more generally — faces what in México is called the ‘cucaracha’ effect, or elsewhere as simply a ‘bubble’ effect. Just as the main battlefield of the drug war in the Western Hemisphere moved from Perú in the 1980s to Colombia in the 1990s to México in the 2000s and, increasingly, to Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador in the 2010s, there’s a worry that a crackdown in Michoacán will only result in more drug violence elsewhere. There are already signs that the Knights Templar are moving into into nearby Hidalgo state — that would bring drug violence calamitously closer to the Distrito Federal; for all the difficulties with Mexican cartels, they have largely steered clear of the federal capital, which has been touched by much less violence than northern Mexico and the Gulf and northern Pacific coasts.

Top photo credit to Alan Ortega / Reuters. Bottom photo credit to Francisco Castellano / Tucson Sentinel.

Wonderful goods from you, man. I have understand

your stuff previous to and you’re just extremely fantastic.

I really like what you have acquired here, certainly like what you’re saying and

the way in which you say it. You make it enjoyable and you still take care of to keep it wise.

I cant wait to read far more from you. This is actually a terrific web site.