Voters in San Marino narrowly preferred to pursue an application for membership to the European Union on Sunday in the first referendum of its kind in the tiny Mediterranean republic.![]()

![]()

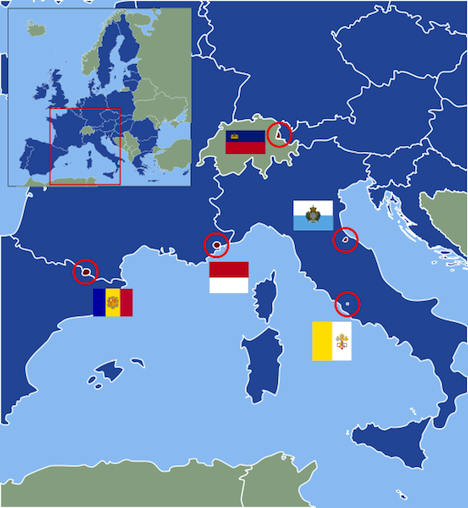

But despite the narrow approval — 50.3% supported EU membership while 49.7% opposed it — supporters did not reach the threshold for a successful referendum (around 32% of all potential voters). That’s just as well, because the European Union is not currently designed to admit microstates like San Marino — or Andorra, Liechtenstein, the Vatican City or Monaco.

San Marino is an independent republic that consists of around 61 square kilometers completely surrounded by Italy. By comparison, San Marino’s population of around 30,000 residents is about 1/22 that of the population of Palermo, the capital of Sicily.

San Marino traces its sovereignty as a republic to the 4th century, and it survived the Napoleonic Wars, papal expansionism, Italian unification and both World Wars (technically neutral in both wars, though its government was controlled from the 1920s until 1943 by the Sammarinese Fascist Party) without being overtaken by the greater Italian state. Its economy is based largely on banking and tourism, and its GDP per capita of around $36,000 provides the ability to fund generous welfare programs.

Proponents of San Marino’s EU membership argue that the tiny country is already subject to so much EU regulation that its membership would give it more at least marginal influence in making European policy in the future. But that’s the same argument that pro-EU Norwegians use to make the case that Norway should join the European Union, and that’s not historically been enough to sway Norwegian voters to embrace membership. It makes more sense in Norway’s case — though the Scandinavian country has just 5 million people, it also has one of the most powerful economies in Europe, and its combination of fiscal discipline and social welfare would make it a touchstone for policymaking decisions. But no one thinks that we’d see an immediate Sammarinese impact on European regulatory matters if San Marino became the 29th EU member tomorrow.

The European Council recently considered the relationships between the European Union and the various microstates in a report issued in 2012 with recommendations for a more standardized approach to what is currently quite a helter-skelter set of arrangements:

- Single market / trade. San Marino, like Andorra, Monaco and Turkey, is party to a customs union with the European Union, but other states (like Liechtenstein) are actually part of the European single market, and the recent European Council report recommended that the European Union should work to integrate all of the microstates more fully into the European Economic Area.

- Open borders / Schengen. Liechtenstein is the only microstate that’s a full member of the Schengen area. San Marino and the Vatican City have open borders with Italy, just as Monaco has an open border with France, but neither are technically members of the Schengen Agreement. Andorra has neither membership in the Schengen Area or open borders with France and/or Spain, so maintains border checks with the rest of the European Union.

- Eurozone / currency. San Marino uses the euro because, like the Vatican, its pre-eurozone currency was tied to the Italian lira, and Monaco has a similar arrangement, given its prior monetary links to the French franc. Liechtenstein uses the Swiss franc, while Andorra has a special agreement for issuance of euro coins with the European Union.

For San Marino, at least, its current relationships with the European Union and Italy mean that it has de facto or de jure access to the single market, benefit of the Schengen free-movement zone and participation in the eurozone. Continue reading Why San Marino (and other microstates) shouldn’t be a member of the European Union