It hasn’t been an incredibly distinguished first six months for the European Union’s 28th member.

Croatia, which entered the European Union on July 1, is only the second state to do so from the former Yugoslav union, but it’s already proving to be somewhat of a problem child — as some Europeans feared openly before its accession.

Most of those fears relate to economics and, given the eurozone’s economic crisis over the past four years, you might have thought that Croatia’s growing pains would be economic in nature, but that’s not the case.

Instead, Croatia’s difficulties have more to do with social issues and historical legacies — in its first six months of EU membership, Croatia caused a showdown almost immediately with EU leaders over the potential extradition of Josip Perković, the former Yugoslav-era director of Croatia’s secret police, and it signaled to the world its relative intolerance for LGBT freedom by conducting a referendum that resulted in a constitutional amendment banning same-sex marriage at a time when much of Europe is embracing equal marriage rights for LGBT individuals.

Those experiences could shape future EU appetite for further expansion in the Balkans, at a time when the European Union has deftly dangled the carrot of EU membership in exchange for a more permanent peace between Serbia and Kosovo, and at a time when EU membership might be the only thing that can save the triple-fractured union of Bosnia and Herzegovina, while also integrating smaller countries like Macedonia and Montenegro into the global economy.

The most serious rupture began three days before Croatia even joined the European Union when it passed the ‘Perković law,’ which purported to prevent the extradition of anyone for crimes committed before August 2002. That caused an almost immediate backlash against Croatia from EU leaders and the other 27 EU member-states, and by September — less than 90 days after Croatia had joined the European Union — EU justice commissioner Viviane Reding, was threatening economic sanctions. Germany, in particular, is interesting in extraditing Perković in relation to his role in the assassination of Croatian defector Stjepan Đureković, who was killed in 1983 in what was then West Germany.

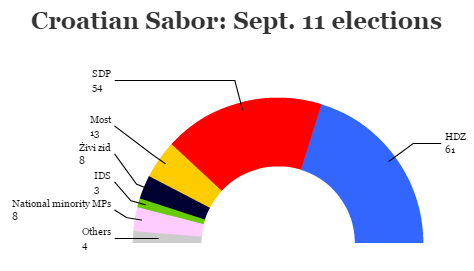

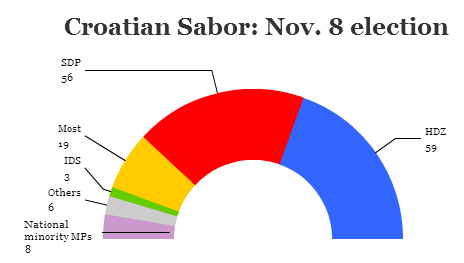

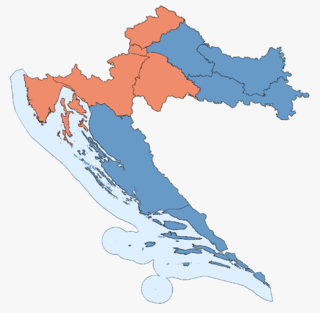

Ironically, it’s the center-left government of Zoran Milanović, who leads the four-party Kukuriku coalition and its largest member, the Social Democratic Party of Croatia (SDP, Socijaldemokratska partija Hrvatske), that dug in its heels over the Perković law, not the more conservative, nationalist opposition party, the Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ, Hrvatska demokratska zajednica), which governed Croatia through much of the EU harmonization period, from 2003 through the December 2011 election. The HDZ, as well as several top government officials opposed the law from the beginning, including Croatia’s foreign minister and deputy prime minister Vesna Pusić, the leader of the second-largest party in the Kukuriku coalition, the Croatian People’s Party/Liberal Democrats (HNS, Hrvatska narodna stranka/liberalni demokrati).

Milanović and the Croatian government eventually backed down in late September by amending the law in a way that complied with EU requirements, but only after Reding instituted formal EU proceedings, needlessly undermining Croatian credibility almost immediately after its EU accession.

Yet almost as soon as the extradition crisis ended, Croatia found itself embroiled in another difficult debate in holding the December 1 constitutional referendum on same-sex marriage. Continue reading Was it a mistake for the European Union to admit Croatia earlier this year? →

![]()