Over the weekend, France found itself engaged in a new, if limited, war — and a new theater of Western intervention against radical Islam.

Over the weekend, France found itself engaged in a new, if limited, war — and a new theater of Western intervention against radical Islam.![]()

![]()

French president François Hollande confirmed that French troops had assisted Mali’s army in liberating the city of Konna — in recent weeks, Islamist-backed rebels that control the northern two-thirds of the country had pushed forward toward the southern part of the country, threatening even Mali’s capital, Bamako.

On Tuesday, Hollande said the number of French troops would increase to 2,500, as he listed three key goals for the growing French forces:

“Our objectives are as follows,” Hollande said. “One, to stop terrorists seeking to control the country, including the capital Bamako. Two, we want to ensure that Bamako is secure, noting that several thousand French nationals live there. Three, enable Mali to retake its territory, a mission that has been entrusted to an African force that France will support.”

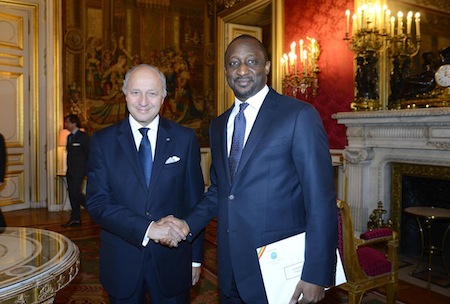

Hollande and his foreign minister, Laurent Fabius (pictured above with Malian foreign minister Tyeman Coulibaly), now face the first major foreign policy intervention of their administration, extending a trend that began under former president Nicolas Sarkozy, who spearheaded NATO intervention in support of rebels in Libya against longtime ruler Muammar Gaddafi and for the apprehension of strongman Laurent Gbagbo in Côte d’Ivoire in 2011.

Foreign Policy‘s Joshua Keating has already called the Malian operation the return of Françafrique. Françafrique refers to the post-colonial strategy pioneered largely by French African adviser Jacques Foccart in the 1960s whereby France’s Fifth Republic would look to building ties with its former African colonies to secure preferential deals with French companies and access to natural resources in sub-Saharan Africa, to secure continued French dominance in trade and banking in former colonies, to secure support in the United Nations for French priorities, to suppress the spread of communism throughout formerly French Africa and, all too often, source illegal funds for French national politics. In exchange, French leaders would support often brutal and corrupt dictatorships that emerged in post-independence Africa.

But to slap the Françafrique label so blithely on the latest Malian action is, I believe, inaccurate — French policy on Africa has changed since the days of Charles de Gaulle and, really, even since the presidency of Jacques Chirac in the late 1990s.

After all, the British intervened just over a decade ago in Sierra Leone to end the decade-long civil war and restore peace for the purpose of stabilizing the entire West African region, and no one thought that then-prime minister Tony Blair was incredibly motivated by contracts for UK multinationals. Given the nature of the Malian effort, it’s quite logical that France — and Europe and the United States — has a keen security interest in ensuring that Bamako doesn’t fall and that Mali doesn’t become the world’s newest radical Islamic terrorist state in the heart of what used to be French West Africa.

Fabius, a longtime player in French politics, and currently a member of the leftist wing of the Parti socialiste (PS, Socialist Party), served as prime minister from 1984 to 1986 and as finance minister from 2000 to 2002, though his opposition — in contrast to most top PS leaders — to the European Union constitution in 2005 has left him with few friends in Europe.

Nonetheless, Fabius argued yesterday that it was not France’s intention for the action to remain unilateral — African forces from Nigeria and elsewhere are expected to join French and Malian troops shortly, UK foreign minister William Hague has backed France’s move, as has the administration of U.S. president Barack Obama — and today, the United Nations Security Council has also indicated its support for France’s efforts as well.

For now, Hollande has the support of over 75% of the French public as well as much of the political spectrum — and it’s hard not to see that the effort will help Hollande, who’s tumbled to lopsided disapproval ratings since his election in June 2012 amid France’s continued economic malaise, appear as a decisive leader. That doesn’t mean, however, that there won’t be trouble ahead for Hollande and Fabius. Continue reading M. Hollande’s little war — and what it means for French-African politics