Raghuram Rajan, the new governor of the Reserve Bank of India, is in Washington this week for World Bank and International Monetary Fund meetings, and he spoke briefly at Johns Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies earlier today, sharing some thoughts about India’s economy — where it’s at today and where it’s going tomorrow. ![]()

Most striking, perhaps, was Rajan’s bullishness that India’s economy has already bottomed out at around 4.4% GDP growth during the summer.

While 4% would be blockbuster growth in the United States or in Europe, it amounts to a drastic slowdown for a country that experienced an economic boom for much of the past decade, peaking at 10.5% GDP growth in 2010. Rajan blamed the usual suspects — India’s poor infrastructure, inadequate human capital development and overregulation during the ‘go-go years,’ but he predicted GDP growth would pick up next year. He also noted that prime minister Manmohan Singh’s current government (a government he advised before his appointment as India’s new all-star central bank governor) has taken appropriate steps over the past year, including liberalizing India’s retail sector, that will put India on a course to return to higher growth in the years ahead.

Here’s what he had to say about some of the other economic issues that he’ll face in the months and years ahead as RBI governor.

India’s current account deficit. Rajan was fairly sanguine about India’s current account balance, which spiraled from a 2% surplus just a few years ago to a nearly 4% deficit today. Rajan blamed the prices of four imports in particular– oil, gold, coal and iron ore. Although India produces about 900,000 barrels of oil a day, that’s just 1% of global production, and India heavily depends on oil imports. While coal and iron ore are abundant, Rajan said that India hasn’t mined enough of either resource because of problems with royalties, environmental concerns, property rights and legal consents. He was hopeful that many of those problems have now been fixed, and that India is set to mine more in the future.

But the largest component, by far, of the current account deficit has been gold imports, and Rajan said that the Indian government’s measures to reduce gold imports (i.e., raising tariffs from 4% to 6%) in the short-term have been successful. One of the drivers of rising demand for gold is the lack of access to banking for millions of rural and poor Indians, and long-term efforts to promulgate wider banking services falls directly within Rajan’s regulatory scope as RBI governor (of course, it’s difficult to slap a tariff on bitcoin).

Banking (and other) infrastructure. Rajan tried to assure that India’s shaky power infrastructure is on the right path, with new power plants coming online to address the country’s growing demand for more energy. He also extolled the Mumbai-Delhi industrial corridor, with its promise of high-speed freight rail, a new six-lane highway, and massive development in the swath of India linking the two megacities.

But it was heartening to hear Rajan talk about transforming India’s financial system as well — he was enthusiastic about issuing new bank licenses, and he pointed to Indian banking innovations like ATMs for the illiterate. While we don’t normally think of banking services as a vital good in the same way as, say, clean water or a stable source of affordable food, access to banking services is a vital element in lifting millions of Indians out of poverty — instead of hoarding rupees (or gold!) at home, greater banking would provide all Indians the reliability of safe savings, deposits and withdrawals.

Fed tapering and the rupee. It’s been clear for some time that the US Federal Reserve’s extraordinary measures to pump liquidity into global financial markets has greatly impacted emerging markets, including India, and it’s arguable that the Fed engendered a bubble in emerging markets over the past five years. That boosted the value of many emerging market currencies, including the rupee, and stoked growth in emerging market countries as investors sought returns that were difficult to find in the United States, especially in a world of zero-bound interest rates. When Fed officials started talking openly about ‘tapering’ off its quantitative easing programs, the rupee’s value dropped along with those same emerging market economies.

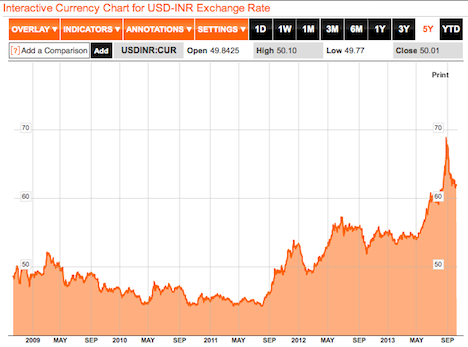

Indian officials are hopeful that the rupee has reached a floor at around 60 to 65 rupees to the US dollar, but if you look at the value of the rupee against the US dollar over the past five years, there’s still quite a bit of room for the rupee’s value to drop further — and the latest plateau in the rupee’s fall may have more to do with the fact that Fed chair Ben Bernanke made clear last month that it’s not yet time to start ‘tapering’:

While Rajan may be one of the sharpest minds in global finance, his hands as RBI governor are tied in the face of the stronger forces of the Fed’s actions. He was hopeful, however, that the Fed’s delay in tapering will give India more time to post a couple of quarters of stronger GDP growth and some adjustments in the current account deficit, thereby steeling the rupee against those forces when tapering really kicks in. Continue reading Raghuram Rajan’s vision of the future of the Indian economy