I’ve been reading an increasing amount of material in advance of the Venezuelan presidential election on April 14 (and will be covering it in Caracas), so luckily for me, Rory Carroll’s newly released book on the Chávez era was right on cue.

Like most thoughtful writing on Chávez and chavismo, Carroll notes how incredibly complex the phenomenon has been — Chávez is neither hero nor villain, and he captures with credibility the reasons why Chávez was, and remains, so popular with a majority of Venezuelans, especially the country’s poorest.

It’s a fascinating read throughout, very highly recommended — I learned something about Venezuela on nearly every page.

The most jaw-dropping parts of the book are those that explain the ‘through-the-looking-glass’ nature of Miraflores, the presidential palace, and El Silencio, the colonial Caracas neighborhood that’s home to Venezuela’s government ministries.

This part of the book felt inspired by Ryszard Kapuściński’s The Emperor, a short (perhaps fictionalized) work on the final years of Ethiopian emperor Haile Sellassie II’s reign, so thick does the sycophancy hang in the air among Venezuela’s ministers — ministers nervously laugh over Chávez’s public claim that capitalism may have killed off life on Mars, and they fret when suddenly Chávez appeared in a yellow shirt (not the trademark red shirt that had become associated with his Bolivarian revolution) and announced there was too much read. What follows is something out of Kapuściński or even Kafka:

Consternation around the palace. What to do? Some ministers hesitantly abandoned the color, worrying it was a trick. Others flashed just a bit of red, trying to gauge the correct level. When, a few weeks later, the comandante resumed wearing red again without elaboration, the crisis passed, and ministers reverted to red.

The winner of the survival game, Jorge Giordani, Chávez’s longtime finance minister, comes off as especially craven and incompetent, the ‘monk,’ a man of austere personal finances who turned a blind eye to widespread corruption and economic mismanagement, all while expending energy to retain his own favor in the administration.

The Castros in Cuba come off as wily as ever, having tapped into Chávez a willing disciple (or, less charitably, a dupe) to provide the ostracized island with precious fuel subsidies and cheap credit, and the relatively rapid infiltration of the G2 Cuban intelligence apparatus into Chávez’s security regime.

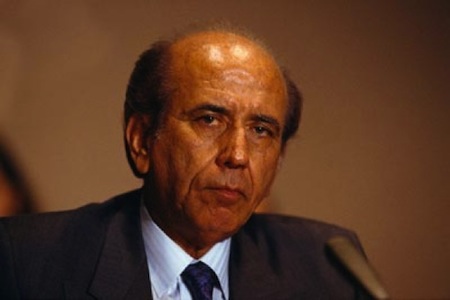

Here too are also details from the ill-fated April 11, 2002 coup against Chávez, and Carroll here paints one of the most damning portraits of Pedro Carmona, who took power for just hours and who, ‘drunk with power,’ literally failed to fit into the gold-plated sphinx chair, feet dangling, in the presidential office in Miraflores.

There are anecdotes a-plenty, too, like the episode of ¡Alo, Presidente! in which Carroll is invited to ask Chávez a question, lobs a mildly critical question, and is treated to a long diatribe about colonialism in the New World, Christopher Columbus and, oddly enough, given Carroll’s Irish background, the British monarchy.

We meet Giovanni Scutaro, tailor to chavismo (and, one suspects, everyone with enough money for fashion in Caracas), the American writer and Chávez enthusiast Eva Gollinger, and Baldo Sansó, a fast-talking executive at Venezuela’s state-owned oil company.

Later in 2010 during an energy shortage, we’re treated to Chávez counseling Venezuela to take three-minute showers:

‘Some people sing in the shower, in the shower half an hour. No, kids, three minutes is more than enough. I’ve counted, three minutes, and I don’t stink.’ He wagged his finger. ‘If you are going to lie back in the bath, with the soap, and you turn on the, what’s it called, the Jacuzzi… Imagine that, what kind of communism is that? We’re not in times of Jacuzzi.’

But it’s not all fun and games and showers.

Despite the histrionics of U.S. conservatives and others, Chávez’s administration been a largely bloodless regime, though there are plenty of chilling tales human rights shortcomings: stories of folks like Raúl Baduel, who was imprisoned on a politically motivated conviction after asserting the separation of the Venezuelan military from politics and becoming increasingly critical of Chávez’s rule, and María Lourdes Afiuni, a judge who delivered an acquittal of disgraced superstar Eligio Cedeño, who thereupon found herself imprisoned. We also meet the Nuñez brothers of the El Cementerio barrio, caught in a bleak life-and-death struggle for survival as the leaders of El Cementerio’s gang in the rough hills above the Caracas valley.

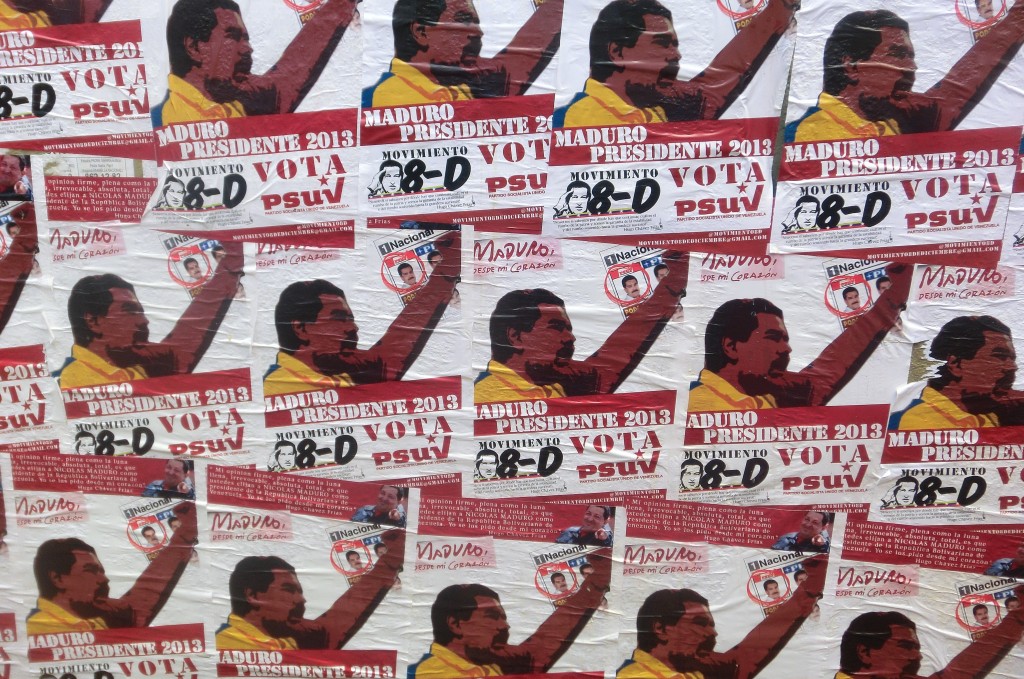

Though Carroll could hardly have known his book would emerge nearly simultaneous with the death of Chávez, its publication comes at a time when both Venezuelans and non-Venezuelans are wondering about what comes next — under either Nicolás Maduro or Henrique Capriles.

I would have liked to see more discussion on how chavismo actually replicates many of the elements of the petrostate of the regimes that preceded it in Venezuela, and in other petrostate regimes throughout the world, as well as more discussion of the future of chavismo after Chávez, but those are topics that could easily be volumes of their own. And it’s notable that neither Maduro nor Capriles play a starring role over the past 14 years. Máduro himself is a bit player in the book, a sycophant who’s managed to survive in El Silencio from the earliest days of Chávez’s ‘Movement for a Fifth Republic’:

Whatever hour Chávez phoned, whatever law he wanted amended or revoked, Maduro assented. He became head of the assembly in 2005 and then, despite not speaking any foreign languages, foreign minister in 2006, a post he held for six years. He crisscrossed the world following Chávez’s orderes and reading Chávez’s script, never deviating, never ad-libbing, never proposing his own initiatives… When the comandante praised Maduro in public — ‘Look at Nicolás there, handsome in his suit, not driving a bus anymore’ — he just smiled. Foreign ambassadors said the foreign minister grew into his job but that he never took a big decision. Only Chávez was allowed to shine, so Maduro did not shine. And thus he prospered. He acquired an extensive wardrobe, put on weight, grew thick around the trunk.

That perhaps explains why Maduro, not the more cunning current assembly president, Diosdado Cabello, won Chávez’s pre-death endorsement as his successor.

Carroll begins with an anecdote from an interview from beloved Latin American writer Gabriel García Márquez, who wrote the following about Chávez on the eve of his inauguration in 1999:

While he sauntered off with his bodyguards of decorated officers and close friends, I was overwhelmed by the feeling that I had just been traveling and chatting pleasantly with two opposing men. One to whom the caprices of fate had given an opportunity to save his country. The other, an illusionist, who could pass into the history books as just another despot.

Carroll’s sophisticated treatment of chavismo produces examples of all of the above — Chávez as savior, Chávez as illusionist and Chávez as despot — and takes chavismo up as a mirror to reflect how all of those impressions have marked Venezuela for the past decade and a half.

![]()