Next week, arguably the two most important countries in the world will kick off two very different leadership transitions.

On Tuesday, November 6, the United States of America will hold a general election. For the 57th time since 1790, Americans will vote for U.S. president, at once the country’s head of state and head of government. The winner will most certainly be one of two men: the Democratic Party incumbent, former Illinois senator Barack Obama (pictured above, right) or the Republican Party challenger, former Massachusetts governor Willard ‘Mitt’ Romney. Americans will also determine who will control the both the lower and upper houses of the U.S. legislature.‡ The new Congress will be sworn in early in January 2013 and the president will be inaugurated (or reinaugurated) on January 20.

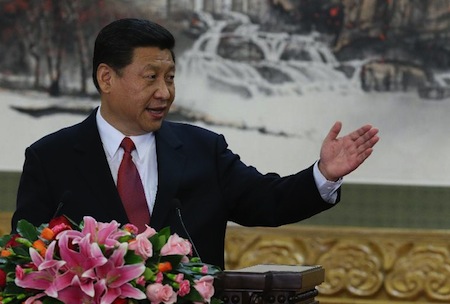

On Thursday, November 8, the People’s Republic of China will watch as the 18th Congress of the Chinese Communist Party (中国共产党) gets underway in Beijing, where all but two of the members of the Politburo Standing Committee, China’s foremost governing body, will step down and new members will be appointed in a once-a-decade leadership transition. China’s ‘paramount leader’ Hu Jintao (pictured above, left), the general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party and PRC president since 2002, is expected to be replaced by Xi Jinping as general secretary, with the other state offices to follow through early 2013. China’s premier, Wen Jiabao, is expected to be replaced by Li Keqiang. Otherwise, the Politburo Standing Committee is expected to be reduced from nine to seven members and will include Xi, Li and five new faces — generally known as the ‘fifth generation’ of China’s leadership.

Despite their vastly different political systems, it’s fitting that the two transitions will coincide so neatly for the two most powerful countries in the world, both so alien culturally and interlinked economically — and there are parallels for both the superpower of the 20th century and a rising superpower of the 21st. For every ‘5,000 years of history,’ there’s a corresponding ‘shining city on a hill.’ The United States has George Washington, Thomas Jefferson and 1776; China has Mao Zedong, Zhou Enlai and 1949.

The United States is the world’s third-most populous country with 315 million people, the third-largest country by land area, and the world’s largest economy with a GDP last year of over $15 trillion. China, meanwhile, is the world’s most populous country with 1.347 billion people, the second-largest country by land area, and the world’s second-largest economy with a GDP last year of $11.3 trillion.

In 2012, if we don’t quite live in a bipolar world, we certainly live in a multipolar world where the United States and China are first among equals, and the U.S.-Chinese relationship will, of course, be a major focus of both governments over the next four years and beyond.

Indeed, Chinese relations have been an issue throughout the U.S. presidential election.

China emerged, if not unscathed, certainly more economically powerful than ever before following the 2008-09 global financial crisis, and China may well have the world’s largest economy within the next decade. But the juggernaut of its double-digit economic growth, which has been fairly consistent throughout the past 20 years, is showing signs of sputtering, and a Chinese slowdown (or even a recession) would have a major impact upon the global economy.

Romney has vociferously attacked China for manipulating its currency, the renminbi, to keep the cost of its exports low, and Obama’s treasury secretary Timothy Geithner has made similar, if more gentle, criticisms. Notably, however, the renminbi has appreciated about 8.5% since Obama took office in January 2009, chiefly because the Chinese government has hoped to cool inflationary pressure.

The level of U.S. debt held by the Chinese government has also become an important issue, especially with the U.S. budget deficit at its highest level (as a percentage of GDP) since World War II. China, however, holds only about $1.132 trillion out of a total of around $15 trillion in U.S. debt, which is down from its high of around $1.17 trillion in 2011 — meanwhile, Japan has accelerated its acquisition of U.S. debt and may soon hold more than China. The outsourcing of jobs previously filled in the United States has long been an issue across the ideological spectrum of U.S. domestic politics, with respect to China and other Asian countries.

In reality, however, other issues are just as likely to dominate the next generation of Chinese and American leadership. With both militaries looking to dominate the Pacific (note the growing U.S. naval presence in the Philippines and throughout the Pacific), geopolitical stability throughout the region will be more important than ever — not just the perennial issue of Taiwan, but growing concerns about North Korea’s autarkic regime, tensions between China and Japan over territorial claims or other future hotspots could all spur wider crises.

As China’s middle class grows in size and purchasing power, and as the United States continues to boost its exports, China will become an increasingly important market for U.S. technology, entertainment and energy in the next two decades. China’s accession to the World Trade Organization in 2001 and its increasing role as a trading partner with the United States mean that trade-related issues — such as the case that the United States brought against China in the WTO last month on cars and auto parts — will only become more important.

But while the U.S. federalist constitutional structure — with its tripartite separation of powers — has been set in place since the adoption of its Constitution in 1787, the Chinese structure is a more recent creation. The Chinese Communist Party holds a National Congress every five years, with a handover of power every ten years, vesting power in a collaborative Politburo Standing Committee that makes all key policy-making decisions, a process that came into being only really with the passing of Deng Xiaoping in the 1990s.

After Deng, Jiang Zemin and the so-called ‘third generation’ of China’s political leadership essentially regularized the current process, and the ‘fourth generation’ led by Hu and Wen that assumed leadership in 2002 and 2003 is now set to pass leadership on to the ‘fifth generation’ under Xi and Li.

China’s party-state essentially has a dual structure: the state institutions of government (the National People’s Congress and the State Council) and the structure of the Chinese Communist Party are essentially parallel — the same people control both. So from a wide base of over 2,000 delegates to the National Party Congress, around 200 will form the Party’s Central Committee, just 25 the more important Politburo and, after next week’s transition, merely seven will form the Politburo Standing Committee. Those seven will also hold the key offices of state — as noted, Li is expected to become China’s premier, the head of the PRC government and Xi, as general secretary of the Party, will serve as the president of the PRC and the chair of the Central Military Commission, the entity that directs the People’s Liberation Army, China’s main armed forces. Continue reading Two systems, two transitions: China, U.S. face leadership crossroads simultaneously →