The first thing you notice about Qinghai province is that it’s rather desolate — more Utah than Alaska, and the first thing you notice about Rebkong is that it’s a dusty town far away from even the provincial capital. A world away from the center of Qinghai, itself a world away from Beijing.

I visited Rebkong in April earlier this year with an American friend based at the time in Shanghai, along with Xining (Qinghai’s capital) and other spots in Qinghai province, which lies in the northwest of the People’s Republic of China. Just a couple of hours away from Beijing by air, Qinghai is indeed a world away, lying as it does on the far east of the Tibetan plateau. With just 5.6 million people, the province contains just a handful of China’s trillion-plus population — the only province with fewer people is Tibet proper, with around 3 million.

We went to Qinghai, frankly, because getting PRC approval for the permits and guides to visit Tibet province has become such an incredible hassle since the 2008 Tibetan protests. A kind of ‘Tibet without Tibet.’ But that was probably too twee a slogan, because Qinghai — known historically to Tibetans as Amdo — is as much Tibetan as what lies within the PRC boundaries of the Tibetan ‘autonomous region.’

The region (Amdo or Qinghai, as you like) has been under Chinese control since it was secured by the Qing dynasty in 1724. It’s home to several important Tibetan Buddhist monasteries, including Kumbum monastery (སྐུ་འབུམ་བྱམས་པ་གླིང།, or ‘Ta’er si’ in Mandarin Chinese, 塔尔寺), founded in 1577 on the site of the birthplace of Tsongkhapa, an important figure in the development of Buddhism and the founder of the Gelug (‘yellow-hat’) school of Buddhism — its importance to Tibetan buddhism is second only to Lhasa, Tibet’s capital. Indeed, what we know as ‘Tibet’ today is really just the western part of the historic Tibetan empire, which included not just Amdo, but Kham, which is now the western part of Sichuan province in the PRC. So we were delighted to see a corner of greater Tibet not already fawned over by Richard Gere and so many others.

Xining itself is a mix of Muslims (Hui Chinese), Tibetans and Han Chinese, but outside the capital, Qinghai is indisputably Tibetan, and it’s the birthplace of Tenzin Gyatso, the 14th Dalai Lama.

After a night in Xining quaffing barley wine at the local Tibetan bar, we found a local guide who agreed to show us around for the next couple of days, beyond just a quick trip to Kumbum, but a true journey into the Tibetan hinterland. We started our days with tsampa, a high-power concoction of yak butter and barley flour (it reminded me of a buttery version of the energy gels you eat during marathons), gorged ourselves on momo (yak-meat dumplings) and snacked on fresh yak-milk yogurt in between visiting monasteries, such as Rgolung (Youning si’ in Chinese), which nestles upon a handful of ledges in the cliffs of eastern Qinghai province.

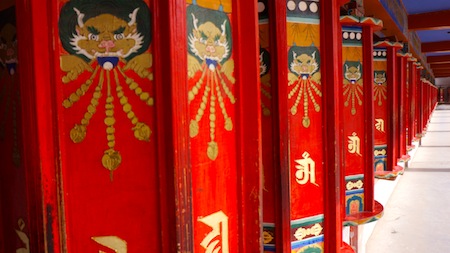

As it so happens, our young, kind guide was from Rebkong, so we spent a night there, and we saw the monastery, Rongwo (pictured above, center and bottom), where he studied as a child and young adult, and we saw the square just outside, Dolma Square (pictured above, top).

That square has become a center of the latest Tibetan protest against the governing Chinese regime when 18-year-old Kalsang Jinpa lit himself on fire [graphic photos] there, one of six Tibetans in the past week to die in a wave of self-immolations in protest of Chinese rule. The situation in Rebkong is becoming tense, according to reports [graphic photos], with 20-year old Nyingchag Bum self-immolating Monday:

A heavy deployment of Chinese armed forces is also being reported in the region.

Thousands of Tibetans, including school students last week carried out massive demonstrations and protest rallies in Rongwo calling for the return of His Holiness the Dalai Lama and freedom in Tibet.

School students also pulled down Chinese flags from their school building and government offices in Dro Rongwo, the place where Tamdin Tso set herself on fire protesting Chinese rule last week.

What’s more, although we can certainly say a lot about Chinese malpractice in Tibet, what does it say about Tibetan culture and the movement for Tibetan independence that it allows — and seems to encourage — such drastic steps among its youngest adherents? Kalsang Jinpa joins Tamdin Tso, a 23-year-old nomad, who lit himself on fire nearby November 7. Most recently, Dorjee Lhundup, a painter of thangka religious scrolls (did he paint one of the two thangka I picked up just eight months ago?) did the same over the weekend.

The self-immolations threaten to steal the spotlight away from what should be an otherwise highly scripted transfer of power from Hu Jintao (胡锦涛) as the PRC’s president, general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (中国共产党) and China’s ‘paramount leader’ to Xi Jinping (习近平) during its 18th National Congress.

Despite the fact that Hu himself in the late 1980s was the Party secretary responsible for the Tibetan region (where he was seen to have deployed PLA force against Tibetans in March 1989 during protests marking the 30th anniversary of the 1959 uprising), Tibet’s seen a resurgence in anti-Chinese sentiment during Hu’s reign, starting with an uprising in 2008 against Chinese rule — and what’s increasingly been seen as an overrun of Tibet by ethnic Han Chinese, who have taken not just land in Tibet, but the best jobs.

As Saransh Sehgal writes in The Diplomat, Hu will bequeath the difficult issue of Tibetan nationalism to Xi this week when he turns over the reigns of the Party and, by 2013, the PRC government, and Tibetans are hopeful Xi will be more receptive to their wishes for self-government than Hu and his predecessors:

Exiled Tibetans have therefore turned their attention to CCP’s leader-in-waiting Xi Jinping. As the number of self-immolations rise, maintaining stability in the restive Tibetan areas will be a key test for China’s next leader, and Tibetan activists have already challenged him to take “immediate steps towards a just and lasting resolution to the occupation of Tibet, or face greater international condemnation and domestic instability.”

For his own part, the Dalai Lama suggested he is optimistic when he recalled Xi Jinping’s father during an interview with Reuters, describing the elder Xi as, “very friendly, comparatively more open-minded, very nice.” Additionally, Xi’s wife, Peng Liyuan, is a Buddhist herself and hosted the first World Buddhist Forum in China. The Dalai Lama went on to say he was “encouraged” by recent meetings he had with Chinese delegates who claimed they were close to senior Chinese officials.

Even names in Qinghai are political — Rebkong (རེབ་ཀོང་) is known as Tongren (同仁县) in Mandarin. By the end of our time, I felt perfectly chastened if I referred to ‘Tongren’ in what is clearly ‘Rebkong’ to the locals.

The Dalai Lama, though it barely seems credulous in 2012, is the same Dalai Lama whose representatives signed the Seventeen Point Agreement in 1951 with Mao Zedong, ceding Tibetan independence to China.

As a matter of background, Tibet was essentially independent from 1912 until the 1950s, when the CCP took gradual control over the province as the People’s Liberation Army entered Tibet unopposed by the Dalai Lama and his forces. As Sam van Scheik writes in his masterful Tibet: A History, the powerful Tibetan monasteries, responsible for much of the region’s education and employment, made two errors in the early 20th century that facilitated Tibet’s re-incorporation into the Chinese state: it refused to allow the 13th Dalai Lama to build a true Tibetan army and it refused to allow the Dalai Lama to modernize Tibet, especially with respect to education.

The current Dalai Lama actually got on well with Mao at a meeting in Beijing in 1954, and believed that the CCP and the PLA had Tibet’s best interests at heart, and the Seventeen Point Agreement initially saw the birth of a renaissance period — the early 1950s was a time of pro-Chinese feeling throughout Tibet. But the violent repression against a Khampa rebellion against Mao’s push for collectivization in 1954 (in western Sichuan province) poisoned the well, and Chinese-Tibetan relations degenerated, and the PLA sieged Norbulingka, the Dalai Lama’s palace in Lhasa in March 1959 during a rebellion against Chinese rule, which led to the Dalai Lama’s exile. Jawaharlal Nehru, then the prime minister of India, granted asylum to the Dalai Lama, who’s never returned to Tibet.

The PLA plundered and destroyed many of Tibet’s monasteries in the following two years and during the Cultural Revolution, essentially working to transform Tibet into a province like any other within the PRC.

More than four decades later, Tibet — and Qinghai province — are clearly home to more Han Chinese than ever, but the self-immolations coinciding with the Party’s transfer of power make clear that China’s ethnic Tibetans clearly still feel like don’t want to be part of any greater China anytime soon, and that will remain an uncomfortable reality as Xi Jinping prepares to take control of China for the next decade.

Photo credits to Kevin Lees — Rebkong, Xining province, China, April 2012.