Not with a whimper, not with a bang, but with $15 billion in financing. ![]()

![]()

This is how the acute phase of Ukraine’s political crisis ends — it’s all about bringing the struggling country back on its feet in economic terms, not a geopolitical fantasy in the minds of Cold Warriors in Washington and Moscow.

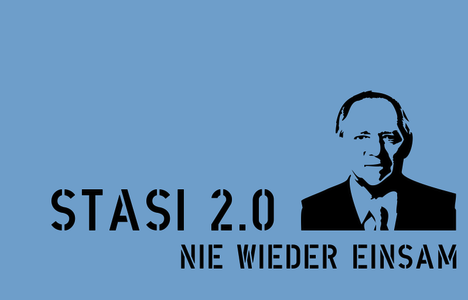

With the European Union’s decision earlier today to deploy €11 billion ($15 billion) in aid, Ukraine’s treasury will now pull back from the brink of sovereign default — a catastrophe that would, ironically, have harmed Russian banks far greater than European banks (Russian investors have a cumulative exposure of nearly $30 billion to Ukrainian debt). That assistance was almost guaranteed from the moment former Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych fled from office after his government unleashed lethal fire on anti-government protesters that had gathered for four months at Maidan Square in central Kiev. Interim president Olexandr Turchinov and interim prime minister Arseniy Yatsenyuk (pictured above with Catherine Ashton, the EU high representative for foreign affairs) are firmly committed to economic reform and Ukraine’s turn toward Europe.

Accordingly, it’s the European Union — and not the United States and not Russia — that looks both most sensible and most productive in the aftermath of last week’s showdown.

Throughout the entire Ukrainian crisis, American and Russian policymakers have routinely disregard the role of the European Union, including some very undiplomatic language from a top State Department official a month ago.

But stabilizing Europe’s expanding periphery is what the European Union does best — and why it won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2012. The earliest iteration of the European Union sutured the wounds among Italy, France and Germany in the 1950s, midwifing the economic expansion of the 1960s. It brought the United Kingdom more closely into Europe in the 1970s, and catalyzed economic reform that transformed Ireland into a high-income country. It smoothed the transitions of Spain, Portugal and Greece from dictatorship to democracy in the 1980s, and its embrace of the former Warsaw Pact states in 2004 anchors economic and political growth from Prague to Tallinn to Warsaw. EU policymakers today are effectively dangling the carrot of EU membership to Serbia in order to bring enduring peace to the Balkans.

Jean Monnet would be overjoyed today to see the European role in ending Ukraine’s crisis, and the promise of extending peace and prosperity more widely beyond the boundaries of Europe’s core. Continue reading Brussels trumps Washington and Moscow over Ukrainian crisis