Michael J. Geary and I argue in The National Interest this morning that the repercussions of reports of the PRISM program within the U.S. National Security Agency mean that U.S. president Barack Obama will face tough questions when he goes to Europe for the G8 summit in Northern Ireland and additional meetings in Berlin. ![]()

![]()

At a time when Europeans are already concerned about the extent of their own governments’ intrusion into their private online lives, the revelations of the voluntary cooperation of service providers like Facebook and the like in allowing U.S. surveillance of foreign communications are already being met with skepticism from top U.S. allies at a crucial and ambitious time for the Obama administration’s European agenda:

The timing of the scandal could not have come at a worse time in EU-United States relations, with both sides set to embark on negotiations for what would be a landmark free-trade compact, the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP).

Above all, German chancellor Angela Merkel is expected to seek assurances from Obama in their one-on-one meetings in Berlin. But with Germany having this week agreed to TTIP negotiations (leaving France as the remaining obstacle), and with the eurozone crisis still not fully over, certainly the Obama-Merkel meeting should have more important business than PRISM.

Ironically, the NSA gathered more pieces of intelligence within Germany during the month of March than any other EU country. A spokesman for Merkel, the first chancellor from the former East Germany, where memories of Stasi surveillance are still fresh, said she would raise the issue with Obama. Her justice minister Sabine Leutheusser-Schnarrenberger stressed, “the suspicion of excessive surveillance of communication is so alarming that it cannot be ignored. For that reason, openness and clarification by the US administration itself is paramount at this point. All facts must be put on the table.”

Ultimately, the Obama administration and the NSA will be less vulnerable to the wrath of European regulators than the companies participating in PRISM themselves.

But Microsoft, Google and other service providers, including Facebook, YouTube, Apple and AOL, could face even more blowback than the U.S. government or the Obama administration. Their apparently voluntary participation in U.S. government’s PRISM program could open them to European lawsuits or otherwise subject them to additional regulatory scrutiny. Significant elements of their businesses are already subject to restrictions within Europe—Google faces strict restrictions on its StreetView program and Facebook’s facial-recognition capability is banned altogether. As PRISM continues to dominate world headlines, Facebook on Wednesday opened its first servers outside of the United States in northern Sweden—its presence there, which like much of Scandinavia is a bastion of government transparency and personal freedom, will come increasingly under the thumb of EU regulators.

I argued yesterday that Sweden is unlikely to come to the rescue anytime soon with respect to Facebook and PRISM. More likely is that the European Parliament will work to pass the new data protection directive that it’s been considering for the past two years and that would place additional restrictions on the processing of personal data, though time is quickly running short with European elections set for May 2014.

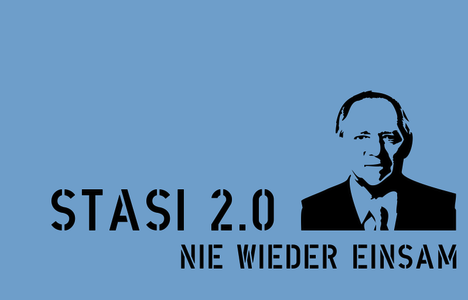

Photo above is a popular graffiti slogan in Germany, showing former interior minister (and now finance minister) Wolfgang Schäuble — critics claimed Schäuble’s focus on counterterrorism measures approached levels of civil liberties intrusion similar to the East German secret police and intelligence force, the Stasi.