After a first-round scare, Juan Manuel Santos won reelection to a second four-year term as Colombia’s president Sunday, delivering a narrow defeat to Óscar Iván Zuluaga and, perhaps more significantly, Santos’s one-time mentor and now opponent, former president Álvaro Uribe.![]()

Though Santos (pictured above) served as Uribe’s defense minister, and won election as president in 2010 with Uribe’s blessing, the former president broke with Santos by opening negotiations with the leftist guerrilla group, Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (FARC, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia). Uribe won support throughout the 2000s from a wide swath of Colombian voters for his aggressive stand against FARC, other guerrilla groups and drug cartels.

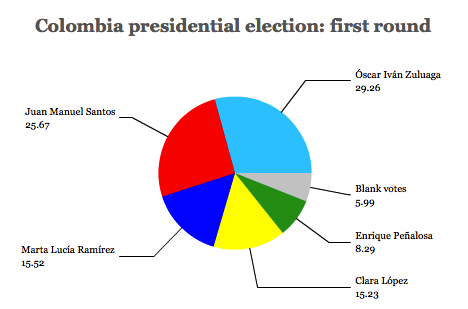

Zuluaga, who won the first round of the presidential election over a divided field, indicated that, if elected, he would impose incredibly harsher conditions on the FARC talks — so harsh that they would almost certainly halt the progress of that FARC and the Santos administration have made.

On Sunday, Santos narrowly defeated Zuluaga by a margin of 50.94% to 45.01%. Santos has the support of a coalition of major parties, including the Partido Liberal Colombiano (Colombian Liberal Party) and the Partido Social de Unidad Nacional (Social Party of National Unity, ‘Party of the U’) that once supported Uribe. Zuluaga was supported by Uribe’s newly formed party, Centro Democrático (Democratic Center) and significant segments of the Partido Conservador Colombiano (Colombian Conservative Party), which had backed Uribe and Santos in the past.

* * * * *

RELATED: Five reasons why Zuluaga is beating Santos in Colombia’s election

RELATED: It’s the economy (not FARC), stupid

* * * * *

Make no mistake — Santos’s reelection is good news for Colombia, good news for the entire region and good news for the United States, which has devoted significant resources to stabilizing Colombia in the past three decades. If there’s any lesson to be learned from the chaos in Iraq over the past week, it’s that insurgencies ultimately require political, not just military, solutions. Military force can subdue and repress internal dissent, but ending a domestic insurgency demands some form of political engagement.

Santos, throughout the campaign, demonstrated that he understands that in a way Uribe and Zuluaga don’t. Though Santos made his fair share of errors as a first-term president, his victory is cause for optimism that the Colombian government will ultimately reach a political settlement with FARC (even on the same day that Colombian security forces launched a successful operation against FARC on election day).

In the final days of the campaign, there was a sense that Zuluaga might, after all, back down from his hardline stance on the FARC talks, which began in late 2012 — 48 years after FARC’s creation.

But you don’t necessarily have to disavow the sometimes controversial aspects of uribismo to acknowledge that the FARC negotiations are a necessary next step. The Colombian military, first under the Uribe administration, and then under the Santos administration, was vital in bringing FARC to the negotiating table, and the current peace talks are, in many ways, the natural progression of Uribe’s successful efforts to marginalize FARC.

From the outset, the FARC talks were never a repudiation of Uribe’s presidency, but an indicator of Uribe’s success. Nonetheless, it was all too easy to imagine Colombia taking a decade-sized step backward under Zuluaga. For that reason, Santos’s reelection is worth savoring. Continue reading Santos win is very good news for Colombia’s peace accords