Among the groups that wield real power in Egypt, democracy turns out to be not so incredibly popular.![]()

![]()

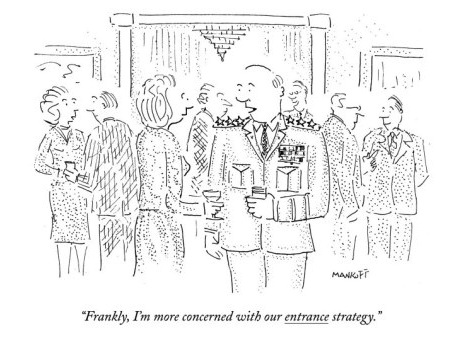

No matter what U.S. secretary of state John Kerry says and no matter what Egypt’s army chief Abdel-Fattah El-Sisi (pictured above) believes, the military effort to push Mohammed Morsi, Egypt’s first democratically elected president, from office was hardly a lesson in preserving democracy. Militaries in healthy democracies, Middle Eastern or otherwise, do not respond to public protests by ousting elected governments.

But Morsi, by pushing through a new constitution without ample debate last December and attempting to assume near-dictatorial powers in order to do so, and more recently trying to stack the ranks of Egypt’s regional governments with rank-and-file Muslim Brotherhood members, showed that he also lacked enthusiasm for civic participation.

What’s happening in Egypt today is starting to resemble a revolutionary moment less and less. Instead, it looks more like the same cat-and-mouse game that the powerful Egyptian military (and the ever-lurking, so-called ‘deep state’), with ties to the United States and a knack for secular realpolitik, has been playing with the today-confrontational, tomorrow-conciliatory Muslim Brotherhood for decades.

In short, Egypt 2013 looks a lot like Egypt 2003. Or 1993. Or even 1973. The Muslim Brotherhood and the countervailing political-military structure have been repeating the same game year after year, decade after decade.

That’s good news for those who are worrying that Egypt looks a lot like Algeria 1991 instead.

The Egypt-Algeria analogy looms ominously today, so it’s worth considering the similarities in some detail. After nearly three decades of rule by the National Liberation Front (FLN, جبهة التحرير الوطني), the guerrilla-group-turned-ruling-party that once liberated Algeria from the French during the bloody war of independence in the 1950s and the early 1960s, Algerians had grown unruly over their country’s progress. On the back of popular protests against Algeria’s government in 1989 over poor economic conditions, officials instituted local elections in 1990. The surprise winner of those elections was the Islamic Salvation Front, a hastily constructed coalition of disparate Islamic elements.

When the Algerian government held national elections in December 1991 to elect a new parliament, the Islamic Salvation Front performed even better, winning 188 out of 231 seats in the first round of the election. The Algerian military promptly canceled the second round of the elections and retroactively canceled the first round, to the relief of the ruling elite that comprised the Algerian pouvoir. The decision also relieved diplomats in Paris and, especially, Washington, where policymakers on the cusp of winning the Cold War did not envision that the new pax Americana should involve landslide victories throughout the Muslim world for Islamic fundamentalists who had no real passion for democracy. As Edward Djerejian scoffed at the time, a victory for the Islamists might amount to ‘one man, one vote, one time.’

The military quickly ousted Algeria’s 13-year ruler Chadli Bendjedid for good measure, then banned the Islamic Salvation Front and instituted military rule.

Sound familiar?

The comparison is particularly worrisome because Algeria’s Islamists fought back with full force and the country descended into a bloody civil war. Although the military subdued what had become an Islamist guerrilla force by the end of the 1990s, strongman Abdelaziz Bouteflika took power in 1999, he remains in power (if not in great health) today, and Algeria has been a semi-authoritarian state ever since. So much for Algeria’s short-lived foray into democracy.

But if there is reason to believe that Egypt is merely falling back into long-established familiar patterns between the military and the Islamists, which have tussled for years without escalating their differences into a full-fledged civil war, and that bodes well for Egypt’s short-term and medium-term stability.

Sure, the faces and the names have changed. Hosni Mubarak’s sclerotic three-decade reign is firmly in the past, Mohamed Hussein Tantawi was forced into retirement, Omar Suleiman died, and Ahmed Shafiq lost the June 2012 presidential runoff to Morsi. But a new coterie of secular and military power-brokers, like El-Sisi and newly enthroned vice president Mohamed ElBaradei have risen in their stead and maybe one day, nationalist neo-Nasserite Hamdeen Sabahi and Ambien-variety Muslim democrats like Abdel Moneim Aboul Fotouh. Egypt’s priority now is to keep either side from any radical lurches. But as long as El-Sisi doesn’t launch a wholesale slaughter of Muslim Brotherhood protesters, it seems unlikely that Egypt could unravel into the kind of civil war that plagued Algeria for a decade.

The bad news is that doesn’t bode well for Egypt’s experiment in democracy over the past two years. Continue reading Egypt 2013 is not Algeria 1991 (whew!), but that’s bad news for Egyptian democracy