CARACAS, Venezuela — Since the end of the Bretton Woods system, or at least since the end of the ‘currency snake’ in Europe that preceded formal monetary union, it’s become difficult not to think about currency in terms other than a floating price determined on the free market.![]()

Sure, China still sets its own currency, and the renminbi may well be undervalued, but that matters less to China because its whole macroeconomic game is exporting. Manufacturers from a factory in Guangdong province assemble their goods, sell them to the United States, and promptly turn over their dollars to the Chinese government, which then exchanges them for renminbi. That’s how China ended up with such a glut of dollars in the early 2000s, and that’s why relatively fewer exports could mean fewer dollars, which could be one of the few market pressures to cause U.S. bond yields to rise after five years of historically low borrowing costs for the U.S. government.

Of crude oil and curses

But in Venezuela, there’s one major export — oil — and that revenue is in the hands of the government. In one sense, economics in Venezuela or in any other petrostate is pretty facile: when the oil price goes up, the country has a boom; when the oil price goes down, the country goes bust. That’s why the oil crisis 1970s and early 1980s were such a great time for Venezuela but such a bad time for the United States, why the cheap-oil era of the 1990s was so bad for Venezuela and, conversely great for the United States. It’s why Hugo Chávez was riding so high in the early 2000s, and why the brief drop in oil prices with the global financial crisis in 2008 and 2009 was bad for Venezuela as well as everyone else.

Unlike China, which had a $231 billion trade surplus in 2012, however, Venezuela’s trade surplus masks its growing dependence on imports, and so the key market for dollars is among those who import those goods (and for Venezuelans who want to take business trips — or shopping trips — to Miami).

For lots of reasons,there are disincentives for homegrown production in Venezuela. Many of those reasons have to do with the behavioral economics aspects of the ‘resources curse’ and the petrostate, but they also include the uncertain business climate under the last 14 years. Why start a farm in 2003 when the Chávez government might decide to expropriate it on live television in 2008? So the country is increasingly importing even those products, such as fresh produce, that it could arguably grow for itself more efficiently. It’s even started importing refined oil products rather than develop the capital to clean the ultra heavy crude that comes out of the ground in Venezuela. A similar dynamic exists in Puerto Rico, where the U.S. government intervened in the 1950s with subsidies for industry during ‘Operation Bootstrap,’ thereby decimating the boricua agricultural sector to this day — produce in tropical San Juan is imported from Florida, Texas and California.

Of dollars and devaluations

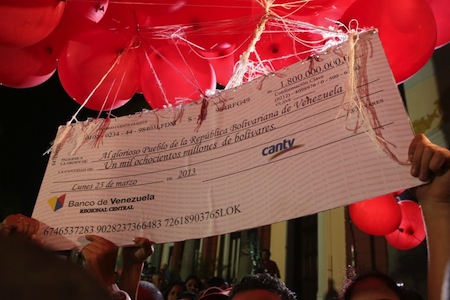

Today, the official rate of the Venezuelan currency, the bolívar, is 6.3 per U.S. dollar.

But no one actually pays that, especially these days.

There’s a black market rate, rumored to be up to four times the official rates, a tourist rate that’s discounted a little from the going black market rate, and even a couple of weeks ago, when the Venezuelan government auctioned off dollars through a new system called SICAD (Sistema Complementario de Administración de Divisas) to currency-starved importers, they didn’t release the price for which the dollars sold, but it’s rumored to be something like between 10 and 15, which is quite a devaluation from the 6.3 rate.

It’s still technically illegal for local media to report any black market rates for the bolívar, of course — through March, at least, you could follow the price through a plucky Twitter account, which slyly presented the daily price for ‘fresh avocados.’ That account — and another one, for ‘fresh lettuce,’ shut down after Venezuelans, their businesses starved for vital dollars, lost their bolívares in a twisted online scam.

The new SICAD dollar auction comes after a formal devaluation in February, which lowered the rate from 4.3 bolívares to 6.3.

It’s fairly common for people to talk about two devaluations, in fact — the first formal devaluation of the official exchange rate from 4.3 to 6.3, and the second informal devaluation, whereby Venezuelans may have been buying dollars from the government for as high a price as 15 bolívares.

(Oh, by the way — the actual price of an avocado? I bought a huge one today for 60 bolívares. A tube of imported toothpaste manufactured in the United States, which is subsidized, costs just 20 bolívares. Another example of the distortions in a heavily-subsidized economy that depends on imports for many of its staples.) Continue reading Not a banana republic, but an avocado economy