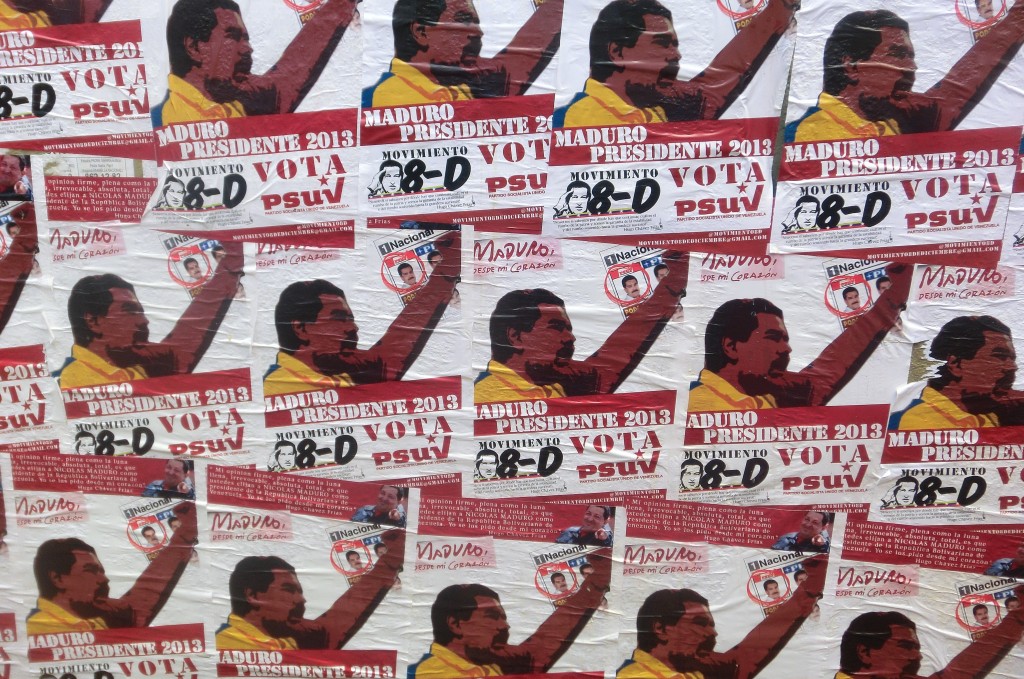

It’s been nearly three weeks since I returned from Caracas to cover the Venezuelan presidential campaign, but the post-election situation there remains far from becalmed, unfortunately. ![]()

Here’s a quick review of where things stand after another week that was, wherever you stand on the Venezuelan political spectrum, not a very good week for Venezuela and its political and legal institutions:

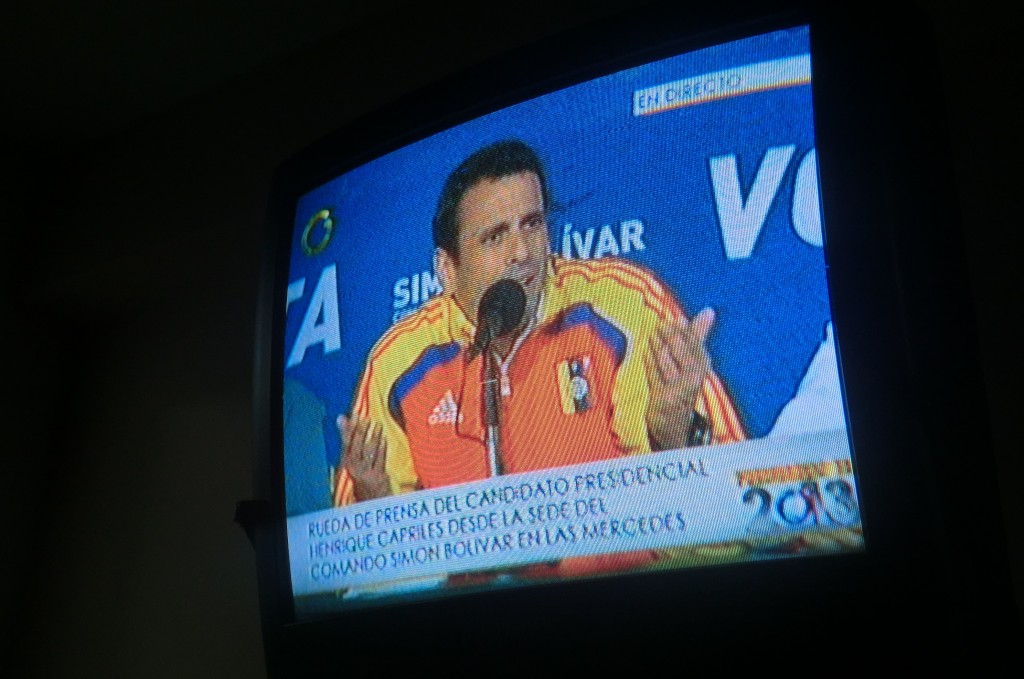

- The opposition candidate Henrique Capriles, who leads the Mesa de la Unidad Democrática (MUD, Democratic Unity Roundtable) coalition, is taking his challenge directly to Venezuela’s Supreme Tribunal of Justice that contests over 2.3 million votes in over 5,700 polling stations from the April 14 vote. A planned audit of the election will continue under the supervision of Tibisay Lucena, the head of Venezuela’s national electoral council, though Capriles and the MUD opposition have rejected the terms of the audit. Although the audit will recount the votes, it will not audit aspects of the voting process, such as voter signatures and fingerprints, that could confirm that the votes were legitimately cast, not just properly tallied. Capriles and his allies have also alleged a wider range of election-day concerns, including voter intimidation and dumped ballot boxes.

- In Venezuela’s Asamblea Nacional (National Assembly), which is dominated by the chavista party, the Partido Socialista Unido de Venezuela (PSUV, the United Socialist Party of Venezuela), opposition deputies have not only been prohibited from speaking, but were attacked in a vicious assault last week on the floor of the National Assembly while its chavista president, Disodado Cabello looked on with a smile. No matter if you’re in Ukraine or in Venezuela, brawling politicians on the floor of a parliament are always unseemly:

- Meanwhile, the government of president Nicolás Maduro has taken an increasingly harsh political line against the United States, attacking U.S. president Barack Obama for ‘meddling’ in internal Venezuelan affairs. Maduro has railed against the Obama administration, which has not yet recognized Maduro’s victory on April 14, and which has aired concerns about the vote. Maduro’s new administration has added additional tension to U.S.-Venezuelan relations by imprisoning a U.S. documentary maker on charges of inciting political violence in Venezuela. Maduro, who suggested during the campaign that the United States may have caused the cancer that killed his predecessor, Hugo Chávez, has argued that the United States is fomenting post-election violence as well. For good measure, he’s also accused former Colombian president Álvaro Uribe of attempting to assassinate him and he’s even attacked Peru’s foreign minister Rafael Roncagliolo.

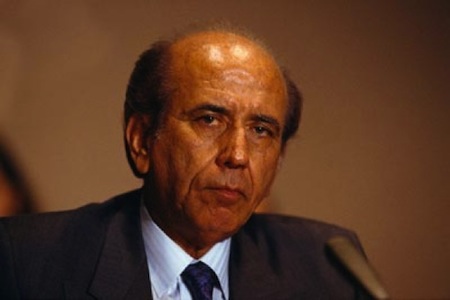

- Maduro’s new cabinet, appointed in late April, looks much like the previous one, with many familiar high-level chavista faces retaining much of the power in Venezuelan government. Rafael Ramírez remains the country’s energy minister and head of the national oil company, Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A. (PDVSA); Elías Jaua, a former vice president, will remain foreign minister; and Cabello remains the president of Venezuela’s national assembly. The longtime head of the finance and planning ministry, Jorge Giordani, will remain merely planning minister and Nelson Merentes, formerly the head of Venezuela’s central bank, will become finance minister, a post he held briefly in the early 2000s as well. Merentes’s promotion has caused some optimism internationally, and Merentes is seen as more of a pragmatist than Giordani and dislikes Venezuela’s currency controls, which have artificially skewed the flow of dollars to importers. It’s not clear, however, that Giordani will relent control over economic policymaking, given that he’s been the economic czar of Venezuelan government since virtually the beginning of the Chávez era.

What is the sum impact of all of this?

So far, it seems that madurismo is the same as chavismo, but with less charisma, fewer petrodollars and the possibility of a more violent government than under Chávez.

With no signs that Capriles is giving up his challenge, Maduro faces a real legitimacy problem, and he’ll continue to do so as long as Capriles challenges the election’s audit process in a court system that’s widely seen as tilted more toward politics than toward impartial interpretation of the law. In the best case scenario, chavismo somehow lost 600,000 supporters between Chávez’s reelection in October 2012 and Maduro’s own election in April. In the worst case scenario, Maduro and the chavista government simply bought, scared or muscled enough votes last month to steal the election. It’s not an enviable position, especially given Venezuela’s ongoing economic troubles.

But Maduro also faces serious challenges within the PSUV and the ruling chavista elite. Continue reading We’re starting to see what Madurismo will look like in Venezuela