Photo credit to Brittany Ann of brittlichty.blogspot.com. Mostar in 2011.

Photo credit to Brittany Ann of brittlichty.blogspot.com. Mostar in 2011.

Bosnia and Herzegovina’s election system might not be the world’s most complex, but it vies with highly fragmented countries like Belgium and Lebanon for the honor.![]()

![]()

![]()

The difference is that Belgium is a wealthy country, and Lebanon, believe it or not, has an economy more than twice as large as the Bosnian economy ($45 billion versus around $17.5 billion) and a much higher GDP per capita ($10,000 versus around $4,600).

The country of Bosnia and Herzegovina quite literally cannot afford its system of government, which was always designed as a temporary structure as part of the Dayton accords that ended its civil war in 1995. More than two decades later, the country is staggering behind even its relatively poor Balkan neighbors, with a ridiculously high unemployment rate of 43.8%. Only Albania and war-forged Kosovo, which hasn’t even achieved universal recognition as a sovereign state, have lower standards of living.

Slovenia has been a member of the European Union for a decade and a eurozone member for five years, while Croatia gained EU membership last July. Serbia and Montenegro are in negotiations for EU accession, and Albania and Macedonia are at least official candidates, Bosnia and Herzegovina joins Kosovo (and Ukraine, Moldova and Georgia) as a merely potential candidate.

Bosnia’s not a hopeless cause. The Bosnian metal industry was the pride of the former Yugoslav republic, and its capital, Sarajevo, hosted the 1984 Winter Olympics. The country’s beauty, with the right infrastructure, could also yield greater tourism interest. Travelers shunning the well-worn path of tourist hotspots like Dubrovnik and Split (not to mention overcrowded Adriatic beaches) could turn to the Sarajevo’s nightlife or to untrammeled mountains and rivers.

* * * * *

RELATED: Bosnia-Herzegovina census highlights tripartite fractures and constitutional problems

RELATED: Will Bosnian protests be the

final straw for the Dayton accords?

* * * * *

The paralysis of Bosnian government should be apparent in the daunting series of elections that the country will endure on October 12.

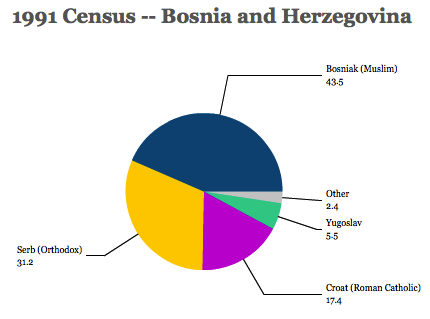

Its national government is fragmented into a tripartite system, whereby each of the country’s three dominant ethnic groups each choose a president. Though it’s mostly ceremonial, the presidency ‘rotates’ every eight months. It’s important insofar as it elects to chair of the Council of Ministers, the day-to-day executive body of the country.

But it’s even more complex in the Bosnian context, because the two major subnational ‘entities’ of the country, the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina (populated chiefly by Bosniaks and Croats) and the Republika Srpska (populated chiefly by Serbs) each has its own president and parliament. Furthermore, the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina is further subdivided into 10 cantons, each of which will elect separate assemblies.

Each of the three ethnic groups has its own political parties that appeal to ethnic constituencies, in the same way that Flemish regional voters choose from among Flemish parties, not Belgian ones, or that Lebanese Maronite Christians or Sunni Muslims choose from among competing Maronite and Sunni factions.

In all three countries, that means that a truly national politics can never really emerge, and no truly national leaders can direct a coherent vision for economic, political and social policy.

Continue reading Bosnia set for elections at all levels of government