With a little patience and a little luck, the 2015 Mexican midterms could have been the magic moment for the long-tormented Mexican left. ![]()

The Partido de la Revolución Democrática (PRD) and one of its founder, Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas, is widely thought to have been fraudulently denied victory in the 1988 presidential election. In the 2006 presidential election, former Mexican City mayor Andrés Manuel López Obrador (or ‘AMLO’) came tantalizing close to winning a race that was presumed his election to lose. In the 2012 presidential election, a race that was supposed to be a runaway landslide for Mexico state governor Enrique Peña Nieto, López Obrador (pictured above) still managed to come within 7% of Peña Nieto.

It’s an understatement to say that Peña Nieto’s presidency has been a disappointment. Mexicans were wary of returning to power the Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI), which governed uninterrupted between 1929 and 2000. Those instincts may have been sharp. Peña Nieto has not inspired confidence in his ability to reduce drug violence and the accompanying corruption that surrounds it, his landmark reforms to liberalize the Mexican state energy company haven’t been followed by subsequent tax reforms, Mexico’s economic growth sluggish by historical standards and Peña Nieto, his wife and finance secretary Luis Videgaray have all been tarred by accusations of personal financial impropriety.

Mexican voters, however, seem disinclined to turn back to the conservative party that held the presidency between 2000 and 2012, the Partido Acción Nacional (PAN, National Action Party), which managed to enact even fewer reforms and performed no better on drug violence. In an alternate universe, that would leave space for a challenge from the leftist Partido de la Revolución Democrática (PRD, Party of the Democratic Revolution). Nevertheless, the party and the Mexican left, in general, is so divided that it is in no shape to emerge as a viable alternative.

For starters, the PRD is just as entangled in the mess of violence and corruption as the PRI. Despite the fact that the Peña Nieto administration has received well-deserved grief for its response to last September’s horrifying massacre of 43 unarmed students in Iguala, the PRD governor of Guerrero state, Ángel Aguirre, was forced to resign after his government did little to seek justice, and it was a PRD official who served as the Iguala mayor accused of involvement in, and cover-up of, the students’ murders.

Out of nine states with gubernatorial elections, the PRD is competing in just two of them — Guerrero and Michoacán, both of which have been plagued by corruption and drug violence in recent years. It not only highlights that the PRD’s roots lie in the indigenous-heavy south, but also that the PRD has failed to become a legitimately national party.

* * * * *

RELATED: From Cárdenas to López Obrador —

why the Mexican left just can’t win

RELATED: Two years in, Iguala massacre

threatens Peña Nieto presidency

* * * * *

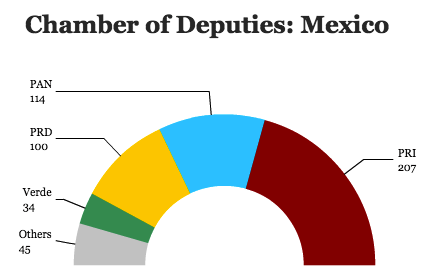

Most polls show that the PRI, despite the pessimism about the country’s course over the past three years, will win the largest share of the vote in the July 7 elections, possibly even perpetuating the party’s narrow hold, with a handful of allies, on the Cámara de Diputados (Chamber of Deputies), the 500-member lower house of the Mexican congress.

Instead of working together to unite toward the common goal of winning power across Mexico in the 2015 midterm elections and propelling the PRD into contention for the 2018 election, its leaders have engaged in petty infighting and recriminations. Continue reading Mexican left disintegrates as midterms approach