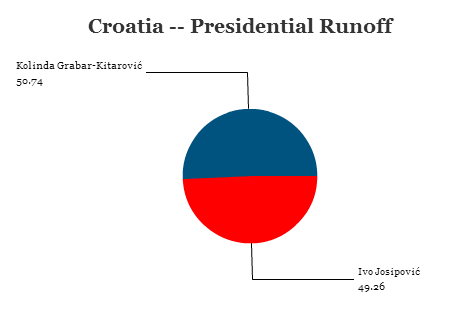

As global politics takes its strongest lunge towards ultranationalist populism in the postwar era, Croatian voters on Sunday delivered a fresh (if narrow) mandate to a conservative party now headed by a moderate and technocratic former diplomat.![]()

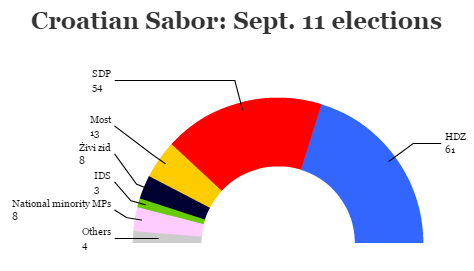

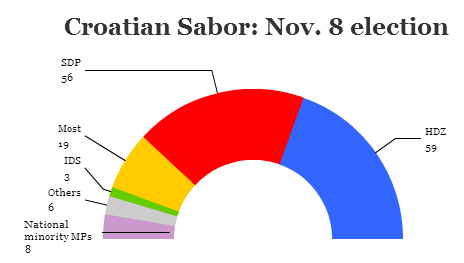

In a repeat of last November’s elections, the conservative Hrvatska demokratska zajednica (HDZ, Croatian Democratic Union) placed first but short of the absolute majority that it needed to govern alone.

Just as after last year’s elections, it will now look to form a coalition with Most nezavisnih lista (Bridge of Independent Lists), a reformist and centrist party formed in 2012 that fared slightly more poorly in the September 11 parliamentary election than last year. Nevertheless, Most continues to hold the margin of power for the next Croatian government, and it’s very likely to join an HDZ-led coalition. Together, the HDZ and Most are just two seats short of a majority, which they might pick up from independents MPs.

Andrej Plenković, a mild-mannered diplomat, is the HDZ’s fresh-faced leader, and he’s part of a rising generation of Croatians who came of age, politically speaking, long after Yugoslavia’s breakup. Though he leads the Croatian right in what has become an increasingly nationalist moment, Plenković’s career is rooted in foreign policy and diplomacy, not populist politics. A longtime member of the bureaucracy in Croatia’s ministry of foreign and European affairs, Plenković served for five years as deputy ambassador to France, then as secretary of state for European integration from 2010 to 2011, shortly before Croatia acceded to the European Union. Since 2013, he has also served as a member of the European Parliament (after a brief two-year stint in the Croatian national parliament).

* * * * *

RELATED: Reform-minded Most party set to play kingmaker in Croatia

* * * * *

Yet as the aftermath of the 2015 election showed, coalition agreements are easier conceived than executed. After 76 days of negotiations, the HDZ and Most agreed in January 2016 to form a coalition headed by a non-partisan prime minister, Tihomir Orešković, a dual Canadian national and pharmaceutical businessman. Tasked with a nearly impossible project to boost GDP growth and cut Croatia’s debt, the government seemed to be on track to meet its goals. Continue reading Croatian conservatives win elections in repeat from last November